Our current exhibition, Charles M. Russell: Storyteller Across Media, centers around the artist’s talent to tell stories through his visual art. Famous for his narratives set in the open range of Montana, Russell wasn’t the only storyteller of the American West.

In the early 20th century, Chip of the Flying U was a popular novel about a ranch in Montana and was written by B. M. Bower. Who was this writer? She was Bertha Muzzy Bower, likely the first female author of mass-market Western fiction.

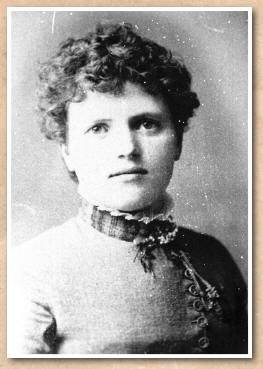

Portrait of B. M. Bower, circa 1890. Courtesy Cascade County Historical Society

Bower had started her writing career as a way to seek financial independence from her first husband. During her lifetime, Bertha wrote sixty-eight novels about the American West, all under the ambiguous pseudonym B. M. Bower. In fact, critics and most of her readers referred to B.M. as a man.

Bertha Muzzy Bower with rifle. Courtesy of University of Oklahoma Libraries, Western History Collections.

Born in Minnesota in 1871, Bower moved to a homestead outside Great Falls, Montana in 1889, where cowboy artist Charles Russell would eventually settle in 1892. Years later, Bower became good friends with Charlie and Nancy Russell after having moved into a house nearby with her second husband. Her time in Montana provided the author intimate knowledge and experiences of cowboy life on the frontier.

Bertha Muzzy Bower on horse 1910. Courtesy of University of Oklahoma Libraries, Western History Collections.

In 1904, Bower published her first Western novel, Chip of the Flying U, which was serialized in Popular Magazine. When Bower published a 1906 edition, the book included three watercolor illustrations by her neighbor and friend, Charles M. Russell. By that point, the cowboy artist was a recognized name and surely added appeal to potential readers.[1] Originals of these reproduced illustrations are found today in the collections of the Gilcrease Museum and Amon Carter Museum of American Art.

Charles M. Russell, The Last Stand, 1905, watercolor on paperboard, 19 3/8 x 22 3/8 in., Gift of the Thomas Gilcrease Foundation, 1955 Philip G. Cole Collection, Gilcrease Museum

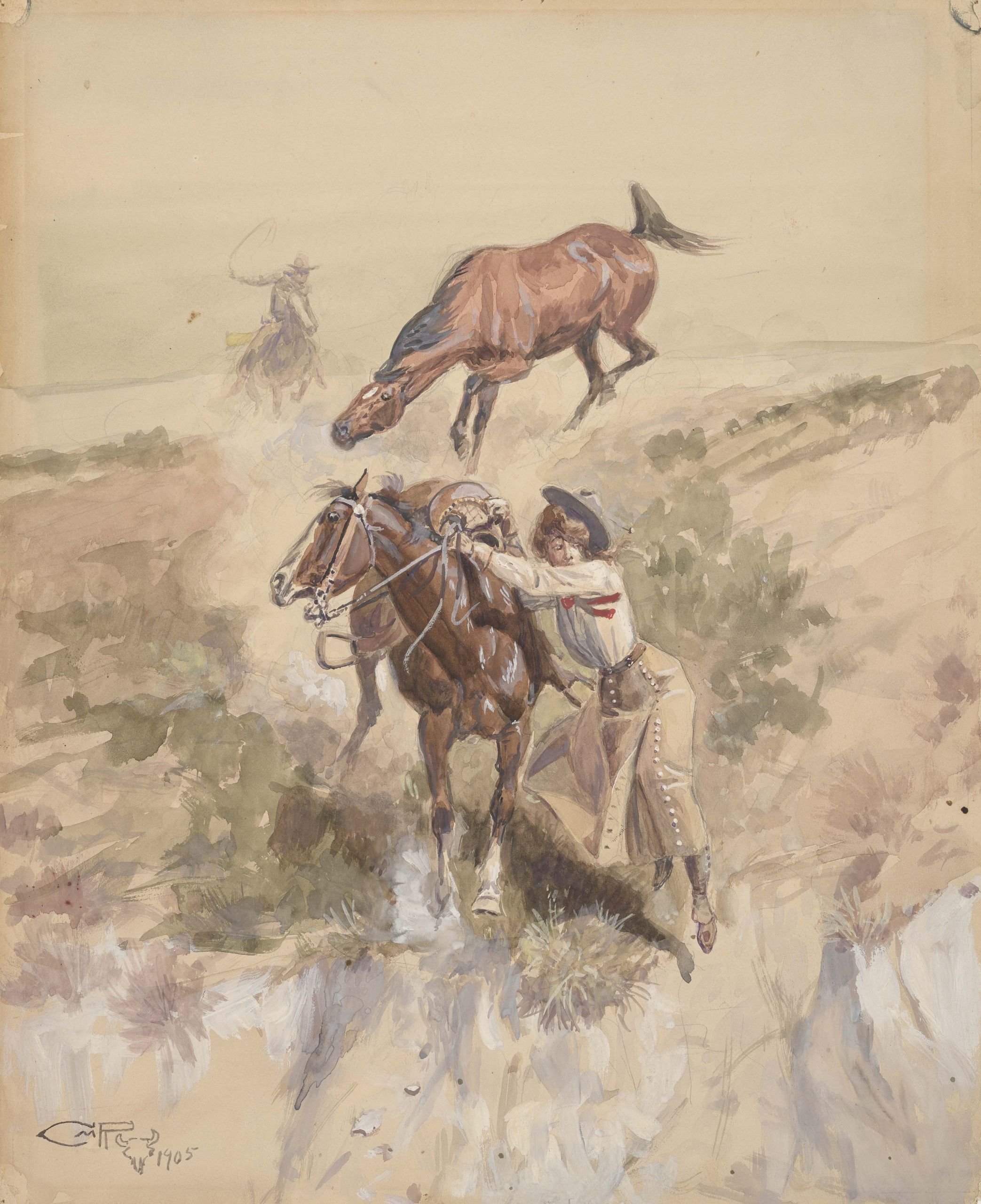

Charles M. Russell, Throwing Herself from the Saddle, She Slid Precipitately into the Washout, Just as Denver Thundered Up, 1905, transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite underdrawing on paper, 14 x 11 3/8 in., Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection, 1961.256

The inclusion of Russell’s artwork reinforced a rumor that the book’s main character, Chip, was inspired by the artist. Chip, like Russell, was a cowboy who had a talent for art despite lacking any formal education, and longed to draw and paint.[2] However, Bower later denied the claim in a letter to Fred G. Renner (a Russell scholar) in 1937 wherein she wrote, “No. Charlie Russell was not the original Chip.” Supposedly Bower didn’t know the cowboy artist until she had visited him to inquire if he would do the illustrations for the book.[3]

Her books were very popular and well-read. Bower, like Russell, knew how to establish mood and atmosphere. Where Russell did so visually through his paintings, Bower did so with her words. In her 1921 book The Long Shadow, she brings to life a cozy ranch kitchen with her description of a tea-kettle “singing placidly to itself and puffing steam with an air of lazy comfort, as if it were smoking a cigarette.” And her characters seem real, normal, and relatable – a reader can gain interest in the character as a person. She makes them “humanly lovable,” as Book Review Digest said of her 1918 book Cabin Fever.

Though her works were fiction, Bower’s stories had a feeling of authenticity, largely due to the fact the writer had lived the life (and the same could be said about Russell and his paintings). In a letter to Adventure Magazine in 1924 she noted that other books and television westerns placed too much emphasis on the violence of the American West. Rather, “There’s more loneliness and monotony in pioneering than there is of battle…Pioneering was, and still is, about ninety percent monotonous isolation and ten percent thrill. It is scarcely fair to turn the picture upside down.”[4]

Unlike Russell, whose work often reveals his nostalgia for a West that had passed, Bower does incorporate modern developments in her western novels such as cars, planes, barbed wire and the general changing of conditions of the American West. Unfortunately, unlike Russell, who had great respect and admiration for Indigenous peoples, in her writing Bower did not treat kindly American Indians, nor Mexicans, African Americans, Mormons, or poor migrants for that matter.

Like Russell, Bower had a connection with Hollywood, developing professional relationships and friendships with several actors like Gary Cooper and Tom Mix. Several of Bower’s novels were turned into movies; her popular Chip of the Flying U was adapted for film four times! The author moved to Hollywood in 1920 with her third husband, where she would continue to write until her death in 1940. In 2017, Bertha Muzzy Bower was inducted in to the Montana Cowboy Hall of Fame.

Bertha Muzzy Bower at typewriter. Courtesy of University of Oklahoma Libraries, Western History Collections.

[1] Stanley R. Davison, “Chip of the Flying-U: The Author was a Lady,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Spring, 1973), p5.

[2] Ibid., 6.

[3] Frank Dobie, Guide to Life and Literature of the Southwest, (Dallas, 1952), p. 97.

[4] Betha M. Bower, Letter to Adventure Magazine, Dec. 10, 1924.

I love that she had a gramophone next to her. That was an important high-tech tool for the musicologists of the time! I wonder what she listened to?