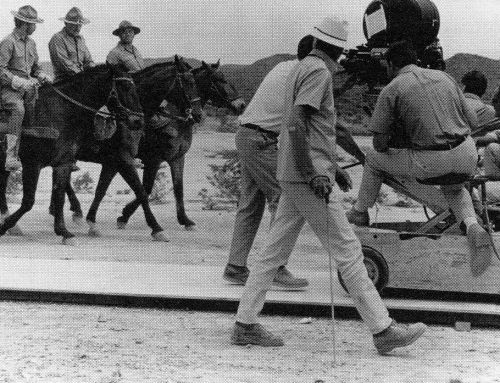

One of the 4 themes in our current exhibit, Picturing the American West, highlights artworks that depict the long-standing narratives of Cowboys vs. American Indians. But as scholars have shown, the conflicts between “cowboys and Indians” are more myth than reality, and were often the product of imagination from dime store novels and popular “Westerns” of film and television.

Attack on the Herd (Close Call) | Charles Schreyvogel | c. 1907 | Oil on canvas | 26.125 x 34.25 inches

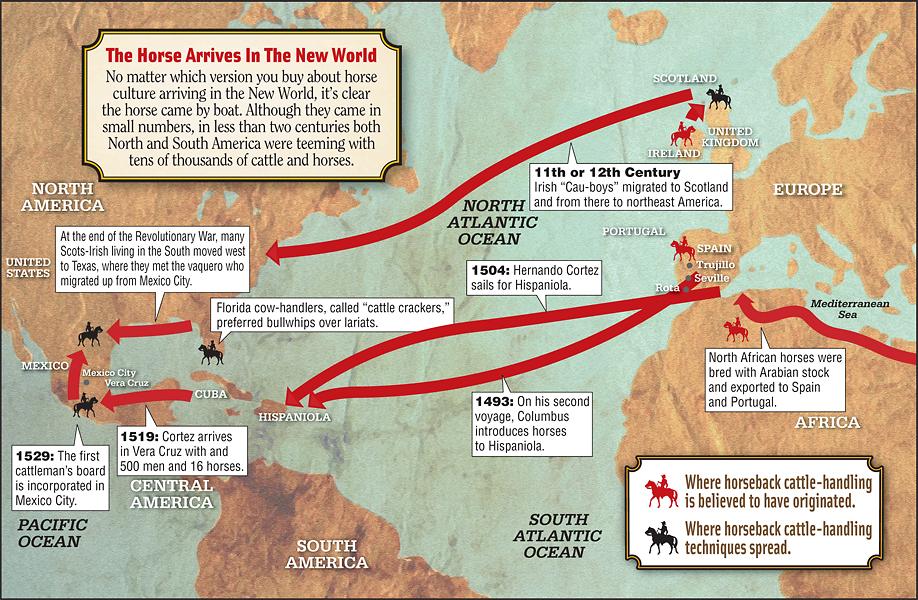

Many who joined the cattle drives of the late 19th century were of African, Mexican, and Indigenous descent. In fact, cowboy culture can trace its roots to many different cultures from all over the world. Michael Grauer – the McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections & Western Art at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum – recently explored the origin stories of western horse cultures with Sid Richardson Museum audiences. In his presentation, Grauer demonstrated how the evolution of the American cowboy is a coalescence of traditions, clothing styles, and technologies from around the world.

“Where is Cowboy Ground Zero?,” True West Magazine

Cowboy culture in the American West can be traced to the Spanish tradition of the vaquero. These were the workers, not the ricos or the wealthy caballeros. What’s the difference between a vaquero and a caballero? A caballero was a gentleman on horseback and a vaquero was a worker on horseback who worked the cattle. The caballero owned the ranch where the vaquero worked, and was often known as a well-dressed man. “Born to the saddle, stylish in his trappings, fearless in his horsemanship, the caballero was one of the most dashing riders the world has ever seen.” – Jose Cisneros, 1984

Parade Saddle | Edward Bohlin | 1947 | Leather, sterling silver, stainless steel, mohair, wool fleece, and wood [Original saddle blanket not displayed]

The Sentinel | Frederic Remington | 1889 | Oil on canvas | 34 x 49 inches

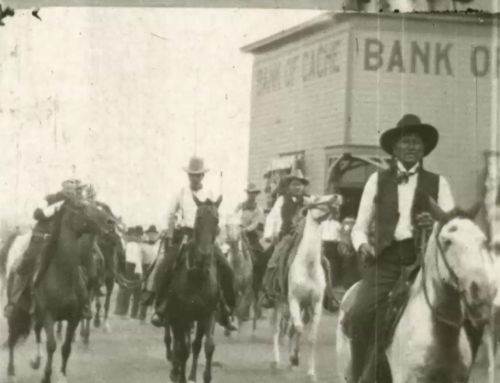

What we know best of cowboys is from the time of the trail drives after the Civil War, when cowboys would drive cattle from land owned by Tejano rancheros down in south Texas and travel up north. Who worked on those cattle drives? Scholars have identified that 1 in 5 cattle trail workers was a cowboy of color, either Hispanic or African American. At that time, most cowboys in south Texas were Hispanic, and along the Texas coast the majority of cowboys were Black. As the cattle drive traveled up the trails, Native Americans joined, so the crews were very much mixed.

When Cowboys Get in Trouble (The Mad Cow) | Charles M. Russell | 1899 | Oil on canvas | 24 x 36 inches

Working alongside vaqueros, Anglo cowboys learned and adopted their tools and techniques. Artist Frederic Remington was well aware of the vaquero and his influence on the Anglo cowboys. He once chided his friend and Western writer Owen Wister for tracing the genealogy of the Western cowboy to that of the knights of medieval Europe. In a letter to Wister, Remington corrected his friend, noting that the traditions of the cowboy were of Latin origin and evolved from Mexico and Texas.

Roping the Renegade | Charles M. Russell | c. 1883 | Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper | 12.5 x 16.625 inches

From the Middle East to West Africa, from North Africa to Spain, from Spain to Central America, the evolution of the American cowboy has been enriched with techniques and traditions from all over the world.

The Cow Puncher | Frederic Remington | 1901 | Oil (black & white) on canvas | 28.875 x 19 inches

“A cowboy without a rope is like a man without arms,” (Albert “Lolo” Trevino, King Ranch vaquero)

Leave A Comment