Our current exhibit, Picturing the American West, is a thematic installation that invites you, the viewer, to explore new contexts and perspectives on Western American Art. The artworks are grouped around four themes, one of which is Western Archetypes. This theme is largely centered around an image of Buffalo Bill Cody in Charles Russell’s 1917 painting, Buffalo Bill’s Duel with Yellowhand.

Buffalo Bill’s Duel With Yellowhand | Charles M. Russell | 1917 | Oil on canvas | 29.875 x 47.875 inches

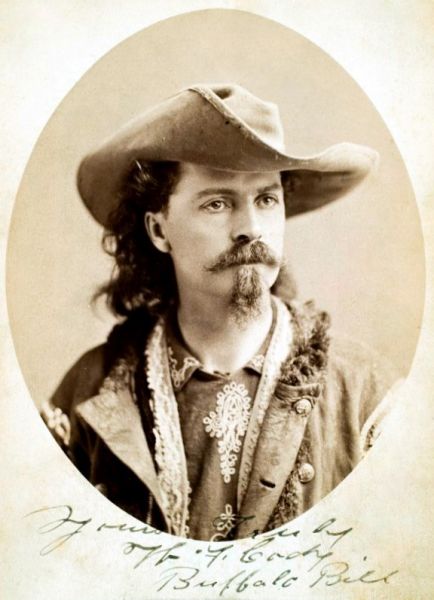

Buffalo Bill Cody, ca. 1875, public domain

Buffalo Bill is the west personified. One story that became closely associated with both the reality and mythology that surrounded the legendary showman was his duel with Yellow Hair (or, as his name has erroneously been translated, “Yellow Hand”). Cody joined the Fifth Cavalry as a scout in the summer of 1876, just weeks after the death of General George Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn—also known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass. Cody’s regiment came upon a party of Cheyenne and following an exchange of rifle fire, Cody shot and then scalped Yellow Hair, waving his war trophy over his head, and reportedly crying, “The first scalp for Custer.”

Many years after Buffalo Bill took his “first scalp for Custer,” Cody told a correspondent in 1903 that Yellow Hair was “the only Indian I ever scalped. I did not believe in scalping.” Why the change of heart? Perhaps, argues scholar Paul L. Hedren, it was a product of his fame: Native Americans featured heavily in his wild west show and the relationships they had built together led him to reconsider his act. “Killing and scalping Indians had become loathsome to Buffalo Bill,” argues Hedren.[1]

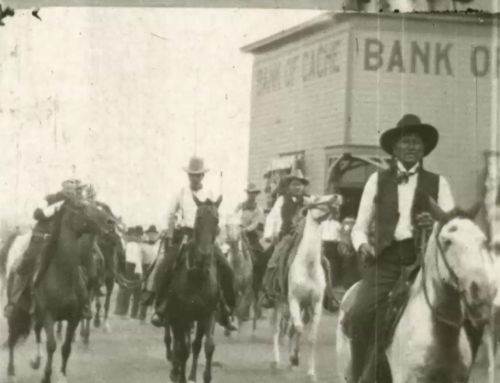

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, 1890, Italy. Courtesy Royale Photographie, Public Domain

Cody founded Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in 1883, which included a collection of performances such as re-enactments of Custer’s Last Stand, riding of the Pony Express, American Indian attacks on wagon trains, stagecoach robberies, and his duel with Yellow Hair. Some of the famous headline performers included Annie Oakley, Calamity Jane, and Sitting Bull. Cody and his show traveled not only throughout the United States but also around Europe as well. In fact, Cody and his show performed in Great Britain for Queen Victoria in celebration of her Jubilee year. Buffalo Bill was everywhere and world-famous. In his own lifetime, Cody became a legend that young boys like Russell read about and idealized.

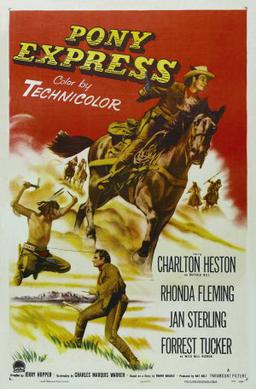

Russell wasn’t the only young boy to look up to Buffalo Bill Cody. In the early 1950’s, young people in the capital of Belgian Congo – today known as Kinshasa – became infatuated with the figure of Buffalo Bill. And how did young people in central Africa learn about Buffalo Bill? Through watching Hollywood Westerns, which were approved by the Belgian colonial censorship commission. One of the most popular movies was the 1953 film Pony Express, starring Charlton Heston as Buffalo Bill.

The young people of Congo were immediately drawn to the icon of Buffalo Bill, who became an eponymous hero and role model of masculinity for a generation of young men under colonial rule. After watching these films, they translated their vision of the American West from the screen onto the streets of Kinshasa, and in the process created a hybrid blend of the Hollywood version of the drifting cowboy with local elements of manhood. Those young people dubbed themselves “Bills,” and every township in Kinshasa had a gang of Bills. While some of these gangs of Bills – or “Billesses” as the female members were called – would sometimes dress in cowboy attire, they also engaged in local practices like body building, martial arts, and magical rituals. This fascinating chapter of our global history was researched and studied by Ch. Didier Gondola, Professor of African History and Africana Studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI). Dr. Gondola wrote a book on the topic in 2016 entitled Tropical Cowboys : Westerns, Violence, and Masculinity in Kinshasa, the findings of which he shared in a recent lecture at the museum, which can be viewed in its entirety here.

Whether through the movie screen, the pages of dime novels, or the canvases of painter like Charles Russell, the legend of Buffalo Bill has made a lasting impact on our ideas about the American West and its archetypal western heroes.

[1] Paul L. Hedren, “The Contradictory Legacies of Buffalo Bill Cody’s First Scalp for Custer,” Montana The Magazine of Western History, Vol. 55, No 1 (Spring, 2005), pp. 16-35, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4520671

Leave A Comment