Our current exhibit, Picturing the American West, focuses on 4 different themes, one of which centers around the essential role the American bison – what is commonly referred to as buffalo – played in the lives of Native Americans.

Indians Hunting Buffalo (Wild Men’s Meat; Buffalo Hunt) | Charles M. Russell | 1894 | Oil on canvas | 24.125 x 36.125 inches

Wounded (The Wounded Buffalo) | Charles M. Russell | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 19.975 x 30.125 inches

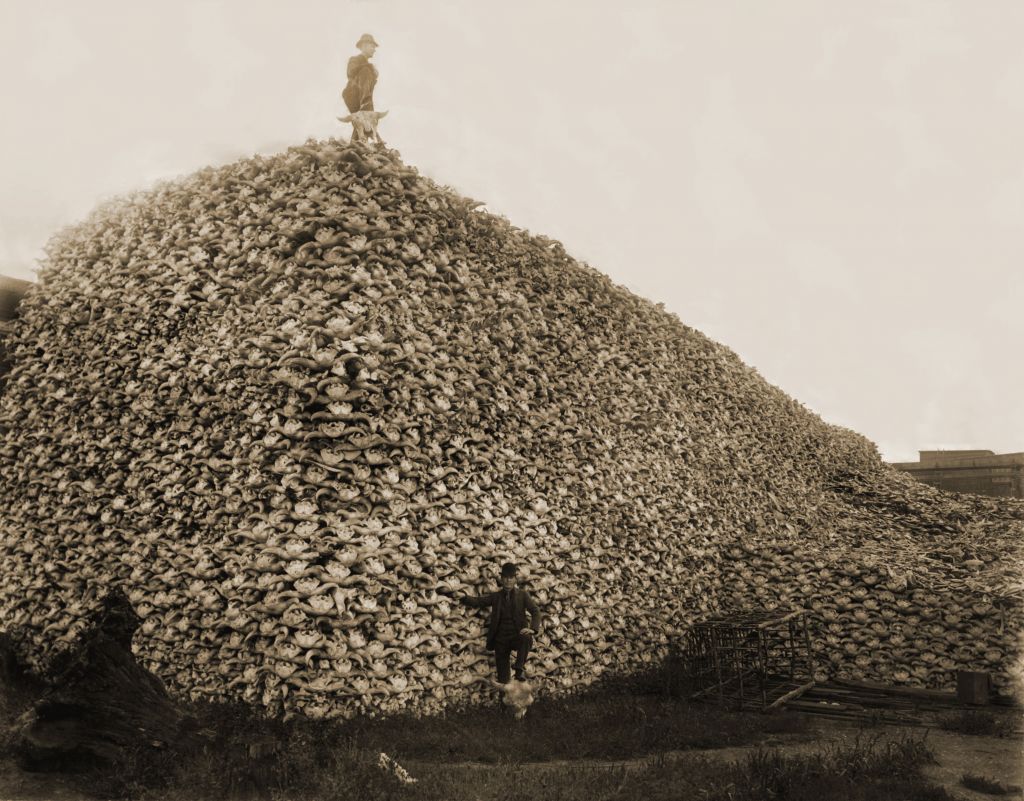

Historians estimate that in the late 18th century, 30 to 60 million buffalo once roamed freely among the grasslands and prairies of the Great Plains and across the Western U.S. But through a combination of forces, including commercial buffalo hunting by colonial settlers as well as the US Army’s active endorsement of the wholesale slaughter of bison herds, and by 1890, bison were near extinction.[1]

Pile of American bison skulls waiting to be processed outside glueworks, Detroit, 1892, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library, Public Domain

Efforts to restore buffalo to the U.S. have been ongoing ever since. One such effort was pioneered by Molly Goodnight, the wife of the famous Texas cowboy Charles Goodnight. Finding the last of the “southern herd” that had taken refuge in the Texas Panhandle, Molly was eager to save these few bison, going so far as to bottle feed and care for young orphaned bison she had rescued. Through her determination, Mrs. Goodnight helped establish an impressive herd – known as the Goodnight herd – near Palo Duro Canyon. That herd had grown to 250 by 1933. Today, descendants of the Goodnight herd are in Caprock Canyons State Park, where they were moved in 1998.[2]

Wild Man’s Meat (Redman’s Meat) | Charles M. Russell | 1899 | Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper | 21 x 30 inches

In 1991, a group of 19 indigenous tribes formed what is now the InterTribal Buffalo Council (ITBC). ITBC is a collection of 69 federally recognized Tribes from 19 different states whose mission is to restore buffalo to Indian Country in order to preserve the indigenous historical, cultural, traditional, and spiritual relationship for future generations. Since its founding, ITBC has restored more than 20,000 buffalo to Tribal lands.[3]

Buffalo are considered a keystone species, which means that they have an impact on their environment. Conservationists recognize the animal’s role in the ecosystem, such as increasing biodiversity, as well as helping seed dispersal and water retention through their dust-walling habits. When buffalo wallow, they create temporary pools and micro-depressions in the landscape that serve as a water source for other animals. Additionally, buffalo hair has been used by certain species of birds to line their nests, keeping their eggs at the appropriate temperature for incubation.[4]

One associate of the ITBC is Fred DuBray, a member of the Cheyenne River Lakota Nation. Mr. DuBray is trying to bring the buffalo back by raising a herd on his ranch in South Dakota. Not only is the restoration of buffalo good for the land, but it’s good for the people of the land as well. DuBray’s daughter Elsie is studying bison meat, theorizing that it provides more nutrients, such as a higher proportion of healthy fats and fewer saturated fats, than beef. Elsie continues her research on Indigenous diets through her studies as a student at Stanford.[5]

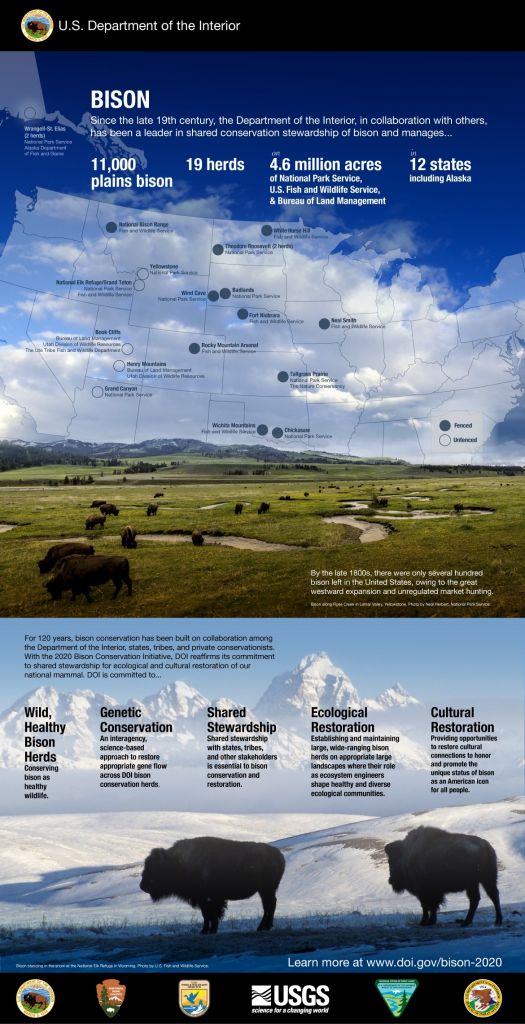

In 2016, the American Bison became the national mammal of the U.S. In 2020, the Department of the Interior announced the Bison Conservation Initiative, a new cooperative effort that will enact conservation strategies for the wild American bison over the next 10 years. This initiative affirms a commitment to the “shared stewardship with states, tribes, and other stakeholders,” that is essential “to address the scale, complexity, and ecological and cultural significance of bison conservation and restoration.” It also commits to “establishing and maintaining large, wide-ranging bison herds on large landscapes, where their role as ecosystem engineers can shape healthy and diverse ecological communities.”[6]

DOI Bison Conservation Initiative

For Native Americans, the restoration of buffalo is as much about healing people and reviving their culture as it is about healing the land. “A lot of non-Indian people can understand {buffalo restoration], and the good it can do for the land,” DuBray says. “Whereas they don’t understand the need to bring the culture back,” he adds. “We were almost wiped out, too. And we need to kind of grow back together. We can help each other.” Today, buffalo remain a vital part of the well-being not only to the land but also to Indigenous communities.

[1] Hanson, Emma I. Memory and Vision: Arts, Cultures, and Lives of Plains Indian People. Cody, WY: Buffalo Bill Historical Center, 2007: 211.

[2] Louie Bond, “Wild Women: Bison and Bears: Molly Goodnight and Bonnie McKinney, Texas Parks & Wildlife, May 2020, https://tpwmagazine.com/archive/2020/may/wildwomen/index.phtml.

[3] Intertribal Buffalo Council, https://itbcbuffalonation.org/.

[4] Jason Baldes, “ We need to ‘see’ buffalo before we can restore them,” High Country News, October 5, 2020, https://www.hcn.org/articles/indigenous-affairs-wildlife-we-need-to-see-buffalo-before-we-can-restore-them

[5] Maddie Oatman, “A Netflix Doc Wants to Fix Our Food System with Capitalism. ‘Gather’ Argues That’s How it Broke,” Mother Jones, November 25, 2020, https://www.motherjones.com/food/2020/11/gather-kiss-the-ground-apache-lakota-yurok-bison-salmon-carbon-soil-regenerative/?fbclid=IwAR36cC0rpHiSrMS5hdXpv_ahF-5-iyDG7uJVG5xQRgUdSvYBeVhnfWLaDPY

[6] Bison Conservation Initiative, National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/bison-conservation-initiative.htm

Charles Russell had a true passion for the Great Western Plains, especially Montana where he lived, worked and closely interacted with indigenous people and their culture. As such the ‘buffalo’ was featured in some of his greatest artworks. Because many of his painting featured the ‘buffalo’, hundreds and thousands of adults and especially students have developed an interest in preserving the buffalo and learning more about their history on the great plains. Thank you Mr. Russell for your part in portraying and preserving the ‘buffalo’!!!

Hear, hear! :)

[…] communicated a story in his work. One of the common narratives in Russell’s art is that of the relationship between Indigenous people of the Great Plains and the American bison. (Note: while bison is the scientific name, buffalo is the more familiar term used […]