At first glance, Charles Russell’s Trouble Hunters might appear to be exactly what it seems: a dynamic portrayal of a war party riding across the rugged Montana terrain, bathed in a rich, golden light. But for Sid Richardson Museum Director Scott Winterrowd, the painting held a mystery just below the surface—literally. What started as a hunch led to a journey through art history, scientific analysis, and the mind of a self-taught Western master. Beneath the vibrant brushstrokes and heroic figures lies a story of artistic revision and discovery, centered around a legendary warrior named White Quiver. As it turns out, Trouble Hunters isn’t just a tribute to the American West—it’s a case study in how a painting can evolve long after the artist first picks up the brush.

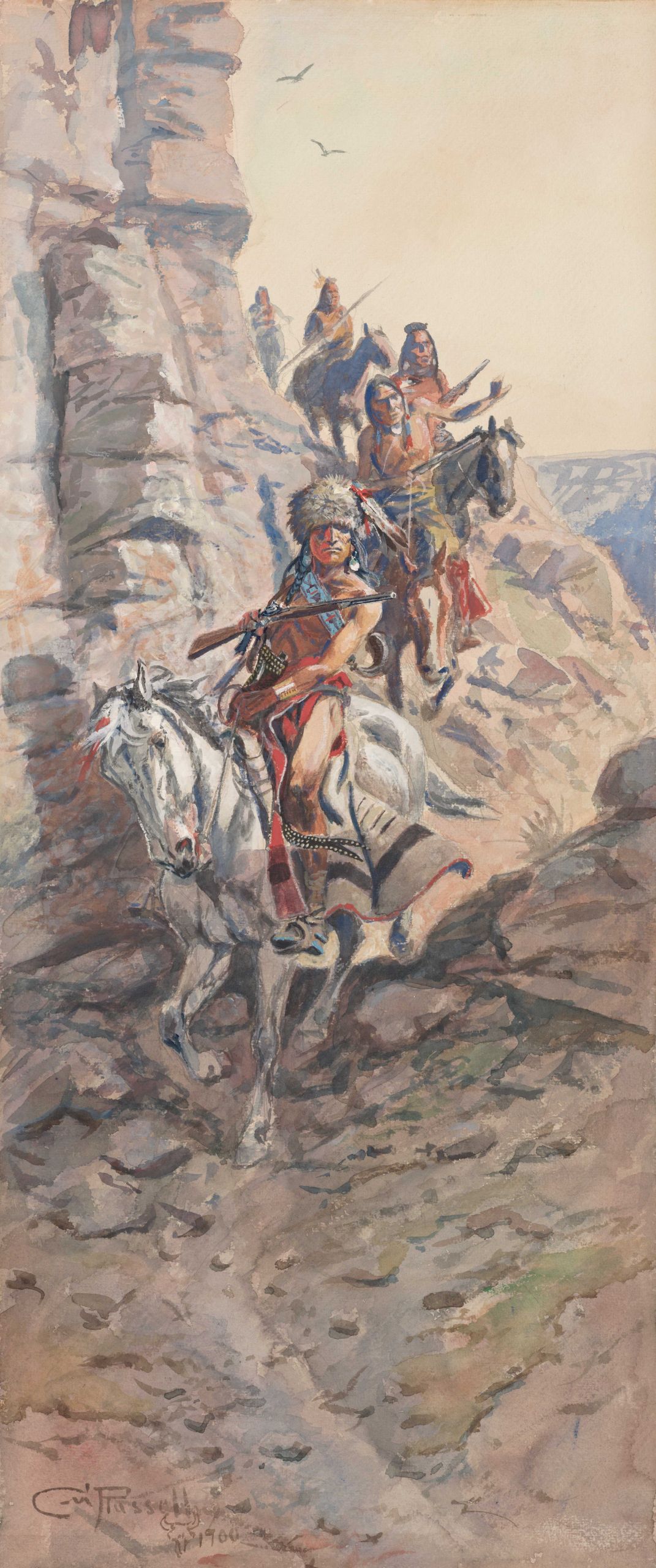

Charles M. Russell, Trouble Hunters, 1902, Oil on canvas, 22 x 29.125 inches

Rock face near Fort Benton, Montana

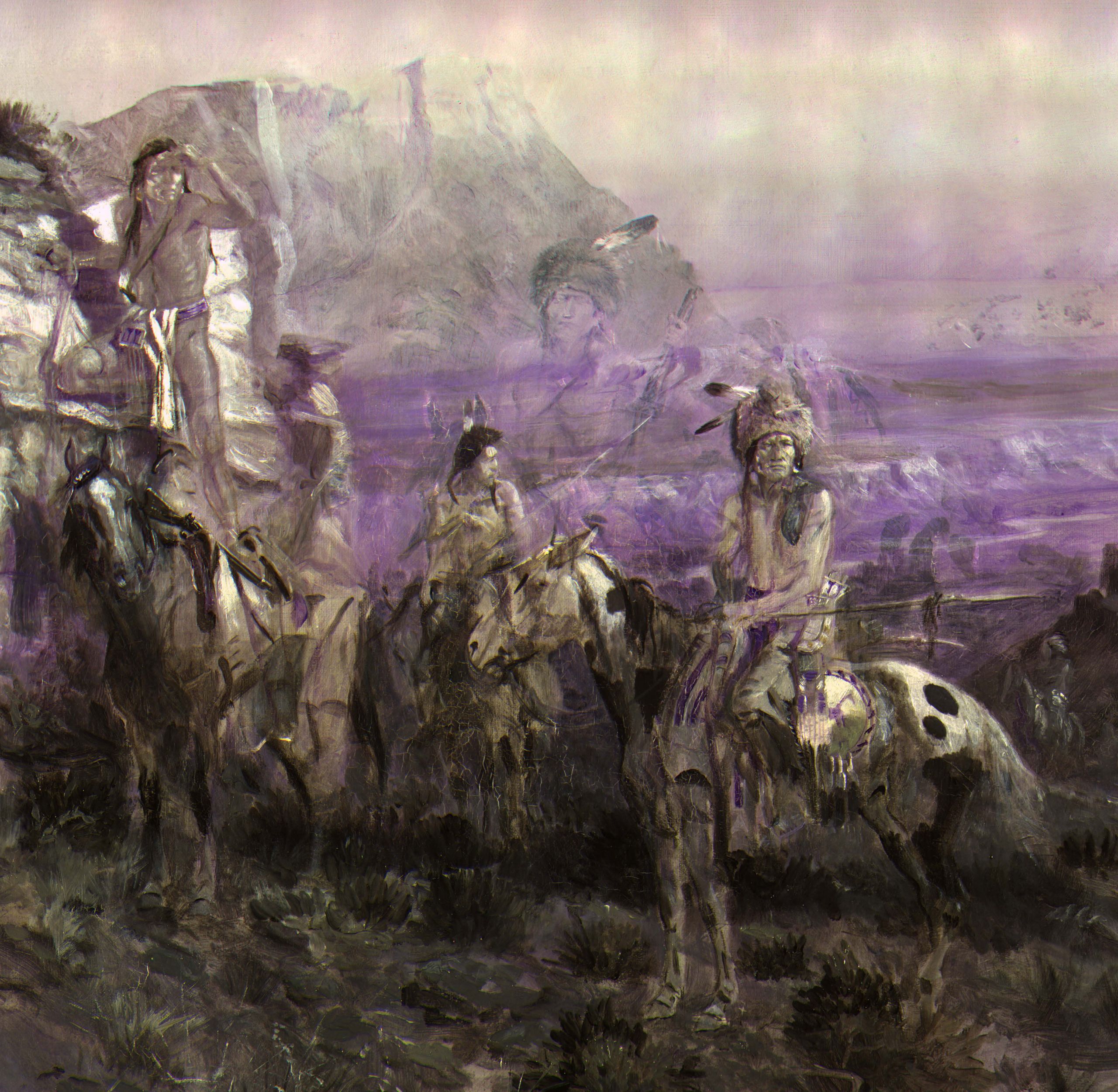

But first, what is Russell depicting in this scene? The area he painted is thought to be around Fort Benton along the Missouri River, about 45 miles north of Russell’s home in Great Falls, Montana. The rocky outcropping behind the figures corresponds to the types of rock formations along the Missouri in that region. For Russell, the image of an Indigenous war party was a powerful symbol of the glory days of the American West. In this case, the artist features a group of Native men led by White Quiver, a Piegan warrior whose story Russell likely knew and painted several times over. He is identifiable in many of Russell’s paintings by his hat, a wolfskin war bonnet with a single eagle feather.

Historically, in the U.S., the Blackfeet lived in the upper Great Plains north of the Missouri River and east of the Rocky Mountains.[1] Much of that area is now the state of Montana. The Blackfeet (or Amskapi Pikuni) are part of the Blackfoot Confederacy,[2] which is the collective name for the four bands: Siksika (Northern Blackfoot), Kainai (Blood), Piikani (Piegan), Aamskapi Pikuni (Blackfeet).[3] The Blackfeet were not the only tribe that Russell portrayed in his work. He also painted the Crow, Shoshoni, Gros Ventre, Sioux, Assiniboine, Sarcee, and Cree. But the Blackfeet were the artist’s first choice when it came to depicting war parties.

Charles M. Russell, Roping By Moonlight, 1900, watercolor, Montana Historical Society, X1976.01.01, Gift of Margaret Sieben Hibbard and family in Memory of Henry Sieben Hibbard

Horse raiding was the most common type of war party among the Blackfeet – and a common motif in Russell’s artwork. The possession of horses meant wealth and power.[4] White Quiver was regarded by the Blackfeet as the most successful horse raider. He developed the unconventional practice of entering an enemy camp at dusk, just as the people were settling down for the night, then bringing the horses out to the other members of his party.

Now here’s an epic legend about White Quiver: during his last raid, when he was thirty – around 1888, when Russell was more cowboy than artist in Montana – White Quiver stole more than fifty horses from the Crow. Military authorities from Fort Benton intercepted him and took the horses. But after nightfall, White Quiver stole back the horses from the government corrals and drove them quickly in Canada[5] There the Mounted Police stopped him and, again, confiscated the horses. And yet again, White Quiver managed to retrieve part of the herd and took them to the Blackfeet reservation in Montana.[6] Years later, in 1892, White Quiver stood trial before the Court of Indian Offenses on charges of horse stealing. The court ended up releasing him due to lack of sufficient evidence.[7]

After his days of conflict, White Quiver had difficulty adjusting to the monotony of peacetime living. Eventually, in 1897 he was given a sergeant’s uniform and enrolled in the Indian Police.[8]

Charles M. Russell, Indian Scouting Party, 1900, Transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite underdrawing on paper, 28 1/8 x 12 in., Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection,1961.169

When Scott Winterrowd joined the Sid Richardson Museum as Director in 2019, he was immediately attracted to Russell’s oil painting, Trouble Hunters, which features White Quiver. The painting boasts a spectacular color palette. Russell dated the painting 1902, but Scott questioned the accuracy of that date. The early 1900s were a transitional period for Russell. It’s not until about 1904 that Russell becomes confident with color and begins to use a more high-key palette, similar to what we see in Trouble Hunters. When you look closely at the picture, you can see reds and oranges, the colors he uses to outline and give a warm edge to the figures. Throughout the composition, Russell plays with color in nuanced ways that aren’t generally what scholars associate with the cowboy artist in 1902.

Questions about the painting continued to linger for Scott during an appraisal of the museum collection in 2022. When the appraisers were looking at the central area of the painting, they noticed a lot of craquelure – a term for the fine cracks that appear in older oil paintings. Generally, fine cracks are not harmful to the painting and are a natural result of aging. Sometimes it can be a sign that the artists reworked a particular area. When an artist repaints on top of a layer of paint, it dries as a different rate, resulting in shrinkage of the paint, and therefore it cracks.

Closeup of craquelure

Scott sent the painting off for study at the Kimbell Art Museum’s conservation lab. To further investigate Scott’s hypothesis, the conservator made an infrared reflectogram. Art conservators use infrared light to see beneath the surface of a painting to create the image. It can reveal things like underdrawings, changes to the composition, and other details that are not visible to the naked eye.

Infrared reflectogram of Trouble Hunters

Detail of infrared reflectogram of Trouble Hunters

Just as Scott suspected! What we see today are the alterations Russell had made to the original composition. The rockface originally extended much further across the composition’s background. White Quiver, off to the side in the resolved composition, was once more central in the picture and more forward, and larger than the rest of the group.

It’s interesting to think about an artist as they’re revisiting their works, particularly in Russell’s case as a self-taught painter. He’s figuring it out as he goes. Maybe he realized the scale didn’t work, and that White Quiver didn’t match the distance from the other riders and background. Russell was rethinking and reshaping his work, playing with size, configuration, and the overall composition. And now we have evidence of the artist and his process!

[1] William Farr, The Reservation Blackfeet (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1984), p. 4.

[2] The Blackfoot Confederacy, https://blackfootconfederacy.ca/.

[3] The Blackfeet Nation, https://blackfeetnation.com/.

[4] Rick Stewart, Charles M. Russell: Watercolors 1887-1926 (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 2015), 188.

[5] John C. Ewers, The Blackfeet: Raiders on the Northwestern Plains (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press,1958), 302.

[6] Rick Stewart, Charles M. Russell: Masterpieces from the Amon Carter Museum (Fort Worth: Amon Carter Museum, 1992), 30.

[7] Journal of Indian Police, 1890-1895, the Blackfeet Archives.

[8] Ewers, The Blackfeet, 303.

Leave A Comment