*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Kay and Velma Kimbell Chair of Art History TCU School of Art, and guest curator of SRM’s special exhibit Another Frontier: Frederic Remington’s East.

Frederic Remington | The End of the Day | ca. 1904 | Oil on canvas | Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, NY

Frederic Remington | The Fall of the Cowboy | 1895 | Oil on canvas | Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, Amon G. Carter Collection

Frederic Remington’s evocative The End of the Day (ca. 1904), one of the highlights of Another Frontier: Frederic Remington’s East, provides an appropriate image for a blog written in December, when short days, long cold nights prevail. The composition may even directly connect to the month, since the painting’s paired horses with sled appeared as a Christmas card drawing the artist sent to his Uncle Bill (ca. 1890s). The End of the Day is, however, less seasonally celebratory and more quotidian in quietly suggesting through the muffling effect of snow the exhausted completion of a workday that likely began fourteen hours earlier. The End of the Day echoes another Remington rendering associated with labor—The Fall of the Cowboy (1895, Amon Carter Museum of American Art)—in several ways, yet that painting conveys by its title the passing of a heroic era, where The End of the Day treats, albeit magnificently, an ongoing commonplace moment.

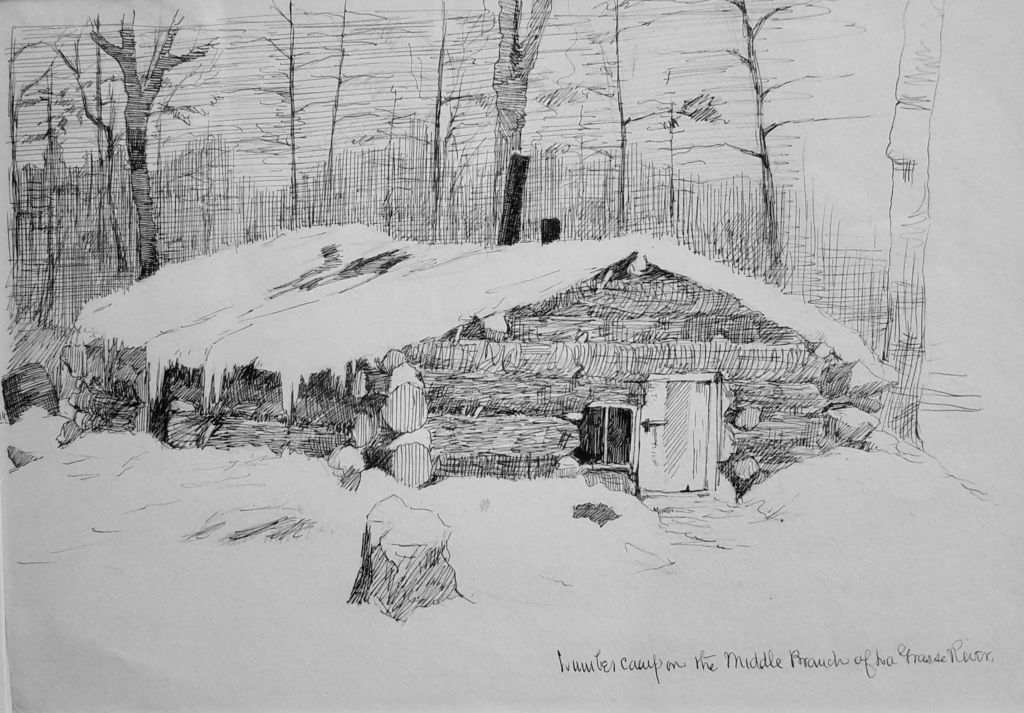

The End of the Day represents a lumbering camp of the kind Remington would have encountered growing up in the North Country. His birthplace Canton sits along the Grass [Grasse] River, in which massive amounts of logs would be floated down to lumber mills annually.[1] The artist’s long-time friend A. Barton Hepburn, who Remington later looked to for financial advice, made his early fortune in the lumber industry. The Frederic Remington Art Museum’s collections includes a watercolor by the artist showing the cookhouse of Hepburn’s lumber camp as well as an ink drawing of, if not the same building, a similar structure.

Frederic Remington | Lumber Camp on the Middle Branch of La Grasse Riber | ca. 1890s | pen and ink | Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, NY

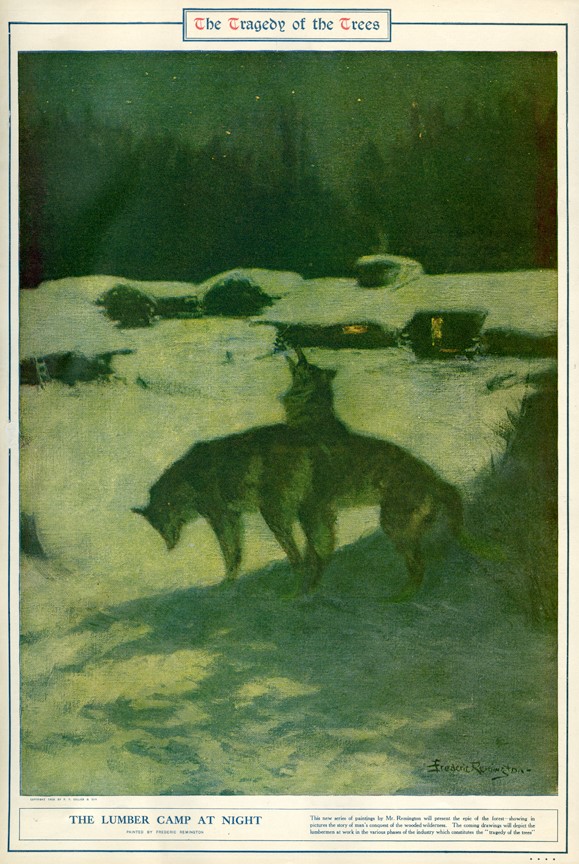

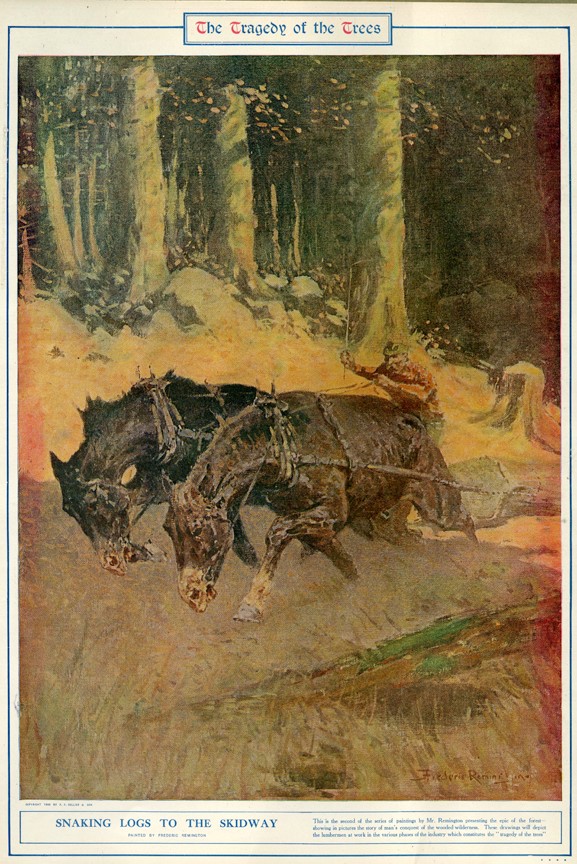

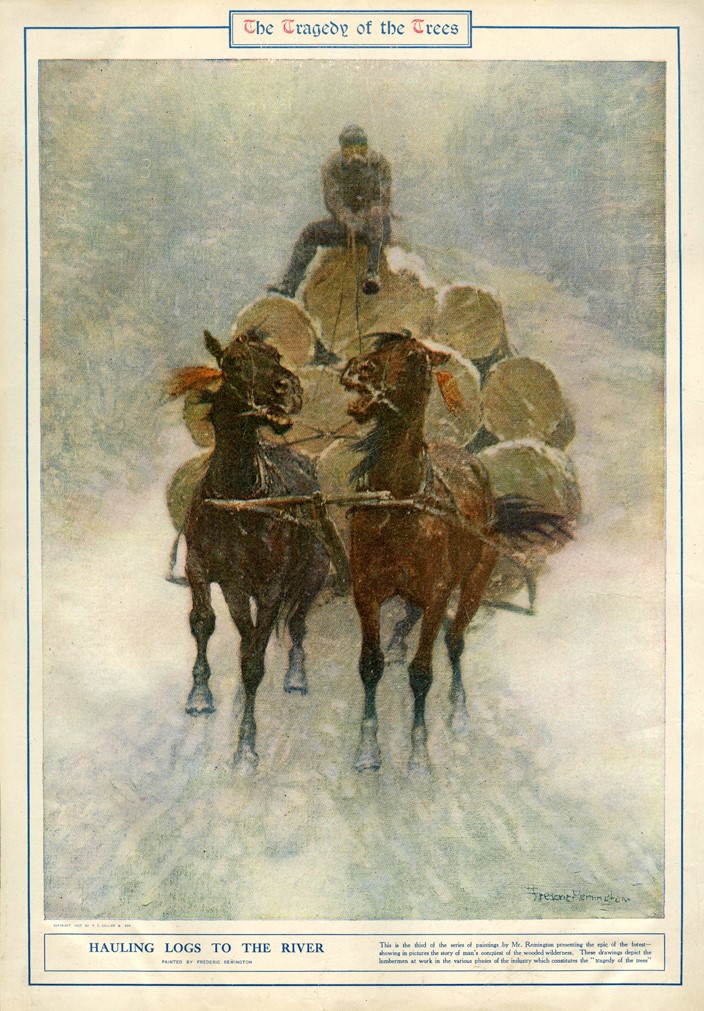

Collier’s Weekly of December 17, 1904 (another connection to this month) featured The End of the Day as a color double-spread page. Remington’s contract with the magazine allowed him to paint a subject of his choice to be reproduced each month. The appearance of The End of the Day anticipated the publication of three more lumber-related compositions in November and December, 1906, and January 1907. The works formed a series called The Tragedy of the Trees, which Collier’s described as “presenting the epic of the forest—showing in pictures the story of man’s conquest of the wooded wilderness. These drawings [sic] depict the lumbermen at work in various phases of the industry which constitutes the ‘tragedy of the trees’.” The series’ title connotes a grand, sweeping theme, not unlike The Fall of the Cowboy (also part of a series, for a Harper’s Monthly article about “The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher”). Although no article accompanied The Tragedy of the Tree images, readers of Collier’s would have recognized Remington’s reference to the rampant deforestation that had occurred (and still was occurring) in the United States, particularly in the Adirondacks.

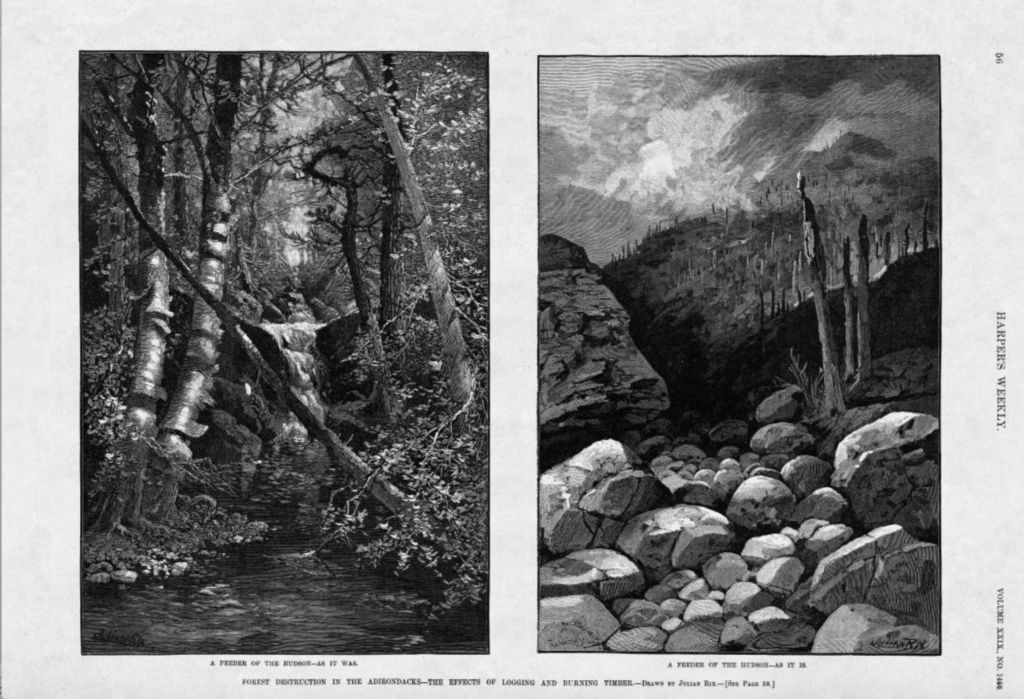

During the second half of the nineteenth century the loss of Adirondack woodlands (part of Remington’s North Country) to lumbering generated widespread concern. For example, the national publication Harper’s Weekly included in its January 5, 1884 issue the article “The Crime Against the Adirondacks,” which declared that due to lumbering: “The vast tract of forest, which feeds the great rivers of the State is being destroyed, and with certain disaster to the State.” A year later, Harper’s Weekly published two “then-and-now” drawings by Julian Rix depicting forest devastation in the Adirondacks. Intriguingly, an undated Rix painting, Adirondacks, hangs among Remington’s personal art collection on view in the Frederic Remington Art Museum.

Julian Rix | Harper’s Weekly | 1885

Anxiety over the depletion of the watershed that Adirondack forests provided led to designating the area a preserve in 1885, a New York state park in 1892, and, by a change in the state’s constitution in 1895, a region to “be forever kept as wild forest lands.” Lumbering continued nevertheless (but more regulated), and Remington did choose to use “tragedy” in his series’ title.

Adirondack Pine, c.1900-10

Of the three pictures only the first one published—The Lumber Camp at Night—seems melancholic, with two displaced wolves (one howling) in the foreground and the snow-laden camp in the cleared middle ground. The other two pictures offer a sense of epic conquest. The second in the series—Snaking Logs to the Skidway—glorifies the immensely powerful horses straining to pull (“snake”) logs out of forest to the platform (skidway) where they would be piled. The horses fit a description of Adirondack lumber country animals, which appeared in a 1903 article on the feeding of horses: “We are safe in saying that the work is the most trying of any class to which horse power is applied. Not only are the loads excessively heavy but the roads are often almost impassable on account of deep snows and heavy grades”[2] (By the way, the writer recommends these horses be fed corn and oats 2:1.) The final image in The Tragedy of the Trees is Hauling Logs to the River, which shows horses charging out of an almost abstract background towards us with their weighty load.

Frederic Remington | The Lumber Camp at Night | Collier’s Weekly, 1906

Frederic Remington | Hauling Logs to the River | Collier’s Weekly, 1906

The impressive The Tragedy of the Trees paintings nicely complement The End of the Day, and exhibiting them alongside it would be fascinating to see. But this could only happen by displaying the reproductions that appeared in Collier’s Weekly, for in 1908 Remington set fire to dozens of his paintings, including the series’ three compositions. That is another tragedy.

[1] For an informative study of logging in the North Country, see Peter H. Vrooman, “Lumbering on the Grass,” The Quarterly [Official Publication of the St. Lawrence Historical Association] 24, no. 4 (October 1980): 3-6, 22.

[2] H. E. Cook, “The Feeding of a Horse,” The Rural New Yorker 62 (October 10, 1903): 781.

[…] for his landscape paintings of California and New York. He also was an illustrator (see the earlier “Tragedy of the Trees” blog). His painting Adirondacks in Remington’s collection is a fine example of Rix’s artistic […]