*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

A Cowboy Chorale

Movement 2

Cowboy Composers

In this second Movement of our Cowboy Chorale we will explore the influence of cowboy songs on American composers in the early 1900s.

Cowboys and Indianists

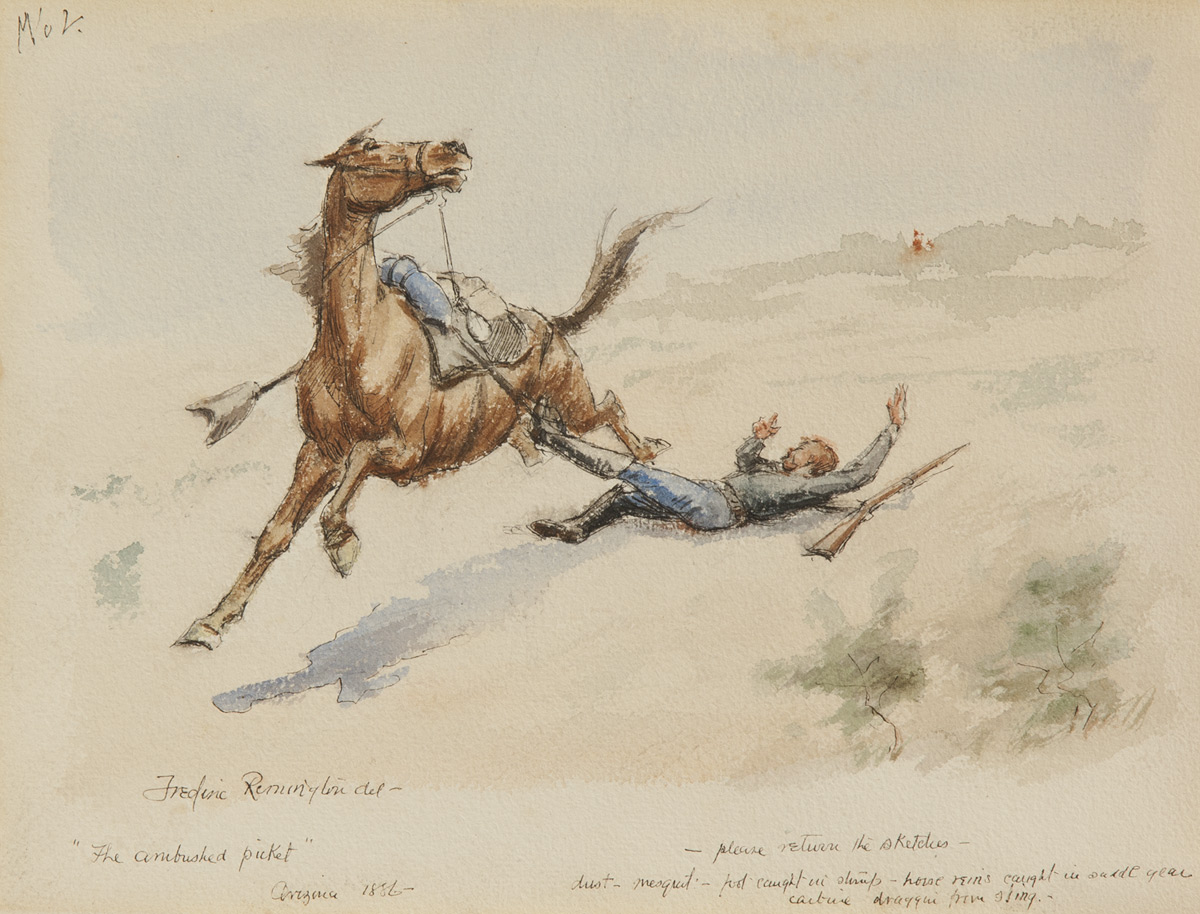

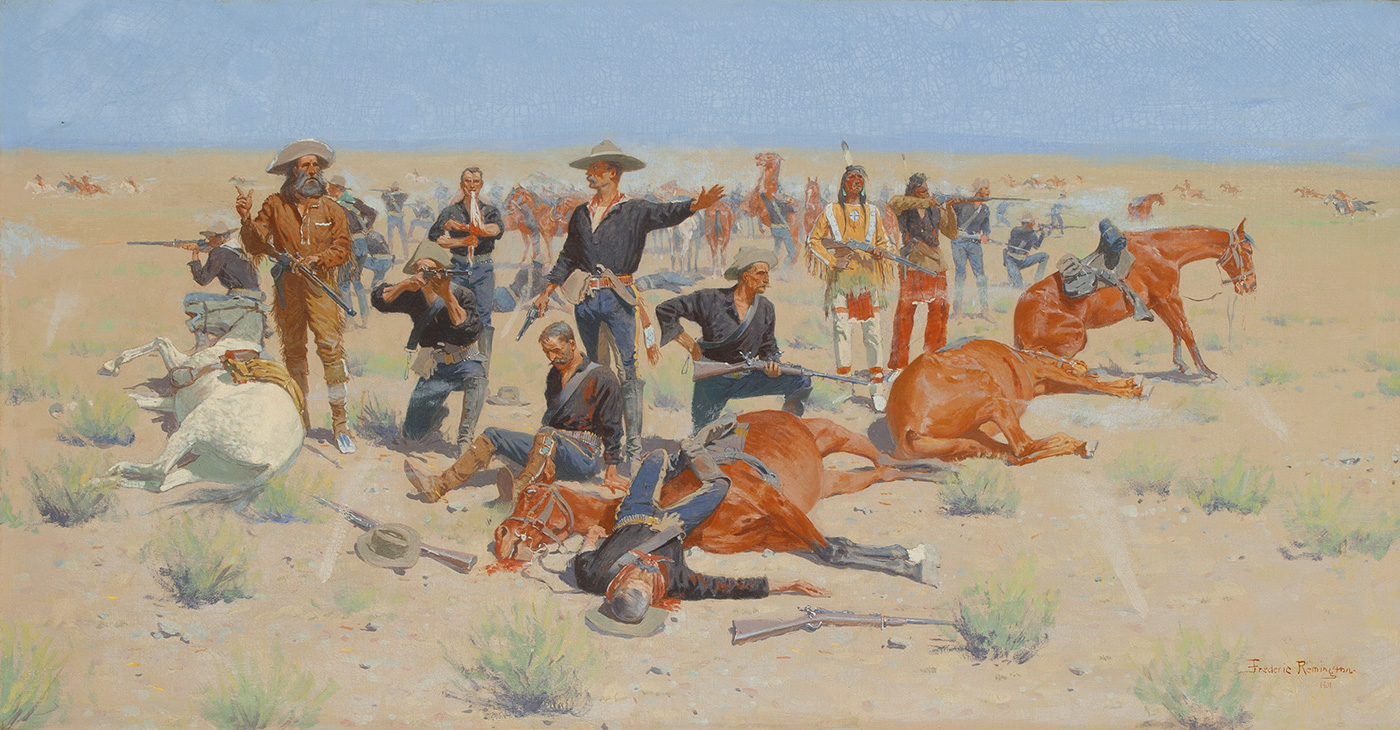

While the unfortunate soul being dragged in Remington’s The Ambushed Picket is most likely a military man, he would probably still suffer the same fate as any dying cowboy – i.e., a burial on the lonely prairie. While listening to the various arrangements of the song “The Dying Cowboy,” look at Remington’s painting and consider the prospect of life, death, and burial out on the Western plains.

Frederic Remington | The Ambushed Picket | 1886 | Pencil, pen & ink, watercolor on paper | 9 x 11 7/8 inches

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, ethnologists, anthropologists, and musicians had been busy recording and transcribing the music of many American Indian tribes. Some of them were also interested in “Negro Spirituals”, songs of enslaved people, and other folk songs, but except for composer Henry F. Gilbert who collected a few stray cowboy tunes, no one was especially interested in what the cowboys were up to.

“The LonePrairee” by Arthur Farwell

One cowboy song that Henry Gilbert recorded was “The Lone Prairee” (sic). He passed it along to fellow composer Arthur Farwell who was an influential Indianist composer. He also founded the

“The Ocean Burial” by George N. Allen (1850)

Wa-Wan Press which catered to Indianists and other serious composers who could find no other publishers for their musical output. The Indianist composers of the early 1900s sought to create an American sound by using Native American melodies; many later turned to other sources including cowboy tunes.

Gilbert’s cowboy song was based on an earlier song called “The Ocean Burial” by George N. Allen (1850) in which a young sailor begged his fellow sailors “Oh, bury me not in the deep, deep sea,” which, of course, they promptly did. Cowboys on the plains bent Allen’s lyrics to their own circumstances, and “The Dying Cowboy” was born. Also known as “Oh Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie,” the song lyrics were published in N. Howard “Jack” Thorp’s book Songs of the Cowboys (1908, 1921, p. 62-62) with the notation: “Authorship credited to H. Clemons, Deadwood, Dakota, 1872. I first heard it from Kearn Carico, at Norfolk, Nebraska, in 1886.”

Arthur Farwell wrangled extensively with his harmonization for “The Lone Prairee” and published it in 1905, making it the very first cowboy song ever published. The same year, he also published “Prairie Miniature”, one of four piano pieces in his collection From Mesa and Plain. It is based on two cowboy songs, including “The Lone Prairee” which comprises the middle of the piece.

“Songs of the Cowboys” by N. Howard “Jack” Thorp, 1908

“The Dying Cowboy” appeared next in Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads by John A. Lomax (1867-1948), who had a life-long interest in cowboy songs, having grown up near a cattle trail in Bosque County, Texas. His “education” at the University of Texas at Austin nearly ended it. Over several years, Lomax had carefully transcribed a personal collection of songs he had heard from cowboy singers. In his autobiography, he described how Dr. Morgan Callaway, Jr., a Johns Hopkins University Ph.D. in Anglo-Saxon language and literature, assessed his collection:

…Timidly, I handed Dr. Callaway my roll of dingy manuscript written out in lead pencil and tied together with a cotton string. Courteous and kindly gentleman that he was, he thanked me and promised a report the next day. Alas, the following morning Dr. Callaway told me that my samples of frontier literature were tawdry, cheap and unworthy. I had better give my attention to the great movements of writing that had come sounding down the ages. There was no possible connection, he said, between the tall tales of Texas and the tall tales of Beowulf. … I was unwilling to have anyone else see the examples of my folly, or know of my disappointment. So that night in the dark, out behind Brackenridge Hall, the men’s dormitory where I lodged, I made a small bonfire of every scrap of my cowboy songs. (John A. Lomax, Adventures of a Ballad Hunter, New York: MacMillan Co., 1947, p. 32)

“The Cowboy’s Lament” by Oscar J. Fox, Jr.

Somewhat crushed, but still undeterred, Lomax continued his education at Harvard, but this time, he was encouraged to continue collecting cowboy songs. He published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads in 1910 (2nd ed., 1916), with “The Dying Cowboy” as the first song in the book, music included.

Oscar J. Fox, Jr. was born on a ranch in Burnet County, Texas, in 1879, and became a professional musician and arranger of cowboy songs. He was particularly focused on the songs collected earlier by Lomax. He arranged “The Dying Cowboy” in 1923, and published it as “The Cowboy’s Lament”. Confusingly, that is also the title for a different cowboy song in both Thorp’s and Lomax’s books.

The Sentinel | Frederic Remington | 1889 | Oil on canvas | 34 x 49 inches

“Arizona” by Charles W. Cadman

The Sentinel depicts a Tohono O’Odham man (or Papago, as they have been called by others) standing guard outside the Mission San Xavier del Bac near Tucson, Arizona, making it an appropriate painting to pair with our next piece, “Arizona” by Charles W. Cadman. Although Cadman was the most famous composer of the Indianist Movement, he was not entirely defined by it, and composed music in many different genres. His “Arizona March” is included here because the cover depicts an Arizona cowboy with his horse near a pueblo. Maybe the sound of the march does convey the feeling of a trotting horse? The piece is dedicated “To Dr. F. H. Redewill and the 158th Infantry Band of Arizona.”

Charles Ives, Ahead of His Time

Charles M. Russell, Cowpunching Sometimes Spells Trouble, 1889, Oil on canvas, 26 x 41 inches

If being crushed to death or injured by a falling horse, as shown in Russell’s painting, was not an especially common demise for cowboys, it may have at least been more than just a passing concern. The main character in several cowboy songs die when they find themselves not on, but under, their steed. Such is the case for poor Charlie Rutlage on the Texas XIT ranch in the cowboy song “Charlie Rutlage”.

Charles Ives (1874-1954) was an American composer whose music was clearly ahead of his time. It wasn’t until near the end of his life that his compositions from decades earlier began to be heard in concert halls. Ives found the lyrics for “Charlie Rutlage” in Lomax’s Cowboy Songs (without music, p. 267), and gave it his “Ives Touch”. It starts off simply enough, then as the music becomes more frantic, the lyrics shift from being sung to spoken – more loudly and more rapidly – until Charlie dies. (This is difficult to convey on Noteflight.com, but recordings are available on Youtube.) At one point in the score, Ives even specifies “Fists” for playing the dense chords.

Oscar J. Fox, More Cowboy Songs

We first heard from Oscar J. Fox above, with the last arrangement for “The Dying Cowboy,” which he renamed “The Cowboy’s Lament”. This was one of many songs from Lomax’s Cowboy Songs that Fox arranged. Here are two more, paired with more paintings at the Sid Richardson museum:

We first heard from Oscar J. Fox above, with the last arrangement for “The Dying Cowboy,” which he renamed “The Cowboy’s Lament”. This was one of many songs from Lomax’s Cowboy Songs that Fox arranged. Here are two more, paired with more paintings at the Sid Richardson museum:

Rounded-Up | Frederic Remington | 1901 | Oil on canvas | 25 x 48 inches

Rounded Up depicts even more unfortunate souls about to meet their Maker. The song “Rounded Up in Glory”, while not necessarily about this particular path to “glory” is, nevertheless, about the “final round-up”, as a cowboy might describe it. Lomax provided lyrics only; Fox composed the music.

Guardian of the Herd (Nature’s Cattle; Buffalo Herd; Before the White Man Came) | Charles M. Russell | 1899 | Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper | 20.625 x 29.125 inches

Deer in Forest (White Tailed Deer) | Charles M. Russell | 1917 | Oil on canvasboard | 14 x 9.875 inches

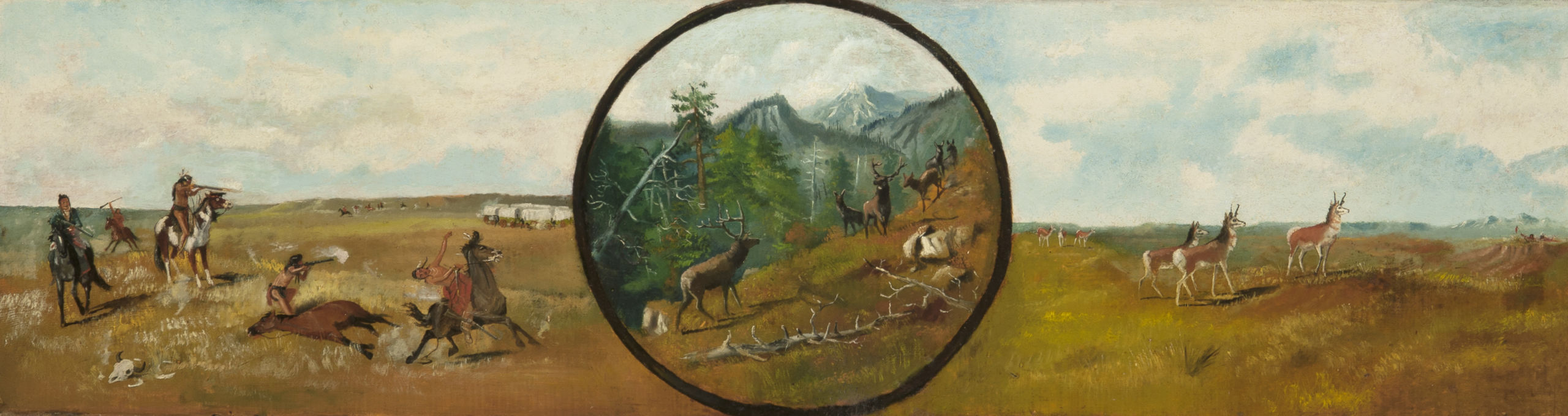

Charles M. Russell, Western Scene (The Shelton Saloon Painting), c. 1885, Oil on wood panel, 17 1/2 inches x 69 inches

It took three of Russell’s paintings just to cover “a home where the buffalo roam, where the deer and the antelope play” (in that order). Look at the animals in Russell’s paintings while listening to different arrangements of this well-known song:

“A Home on the Range” (John Lomax, 1916)

“A Home on the Range” (Oscar J. Fox, 1925)

Estelle Philleo, “Setting the West to Music”

Façade of Sid Richardson Museum, Photo Courtesy of Keith Barrett

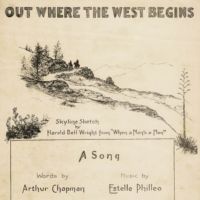

In 2007, Tutti Portwood, a former docent at the Sid Richardson Museum, introduced the new docent class to the museum with a discussion of Fort Worth’s motto/slogan, “Where the West Begins.” The phrase is from a poem by cowboy poet Badger Clark. At Amon Carter’s insistence, it was adopted as the city motto and put on the masthead of the local newspaper, the Star-Telegram. Incidentally, anyone living in the Fort Worth area who has an interest in western art may want to check with the museum about the next docent class. It’s a lot of fun.

In 2007, Tutti Portwood, a former docent at the Sid Richardson Museum, introduced the new docent class to the museum with a discussion of Fort Worth’s motto/slogan, “Where the West Begins.” The phrase is from a poem by cowboy poet Badger Clark. At Amon Carter’s insistence, it was adopted as the city motto and put on the masthead of the local newspaper, the Star-Telegram. Incidentally, anyone living in the Fort Worth area who has an interest in western art may want to check with the museum about the next docent class. It’s a lot of fun.

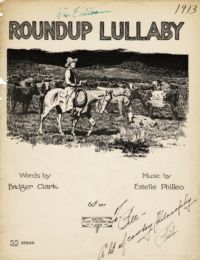

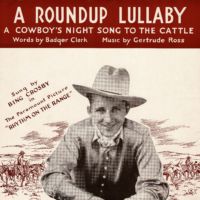

Estelle Philleo (1881-1936) composed and arranged western and cowboy music. In 1917, she set Badger Clark’s poem “Out Where the West Begins” to music, did the same for another of his poems in 1919: “Roundup Lullaby”. In 1922, Gertrude Ross arranged a different (sort of) version of “A Roundup Lullaby” which was sung by Bing Crosby in the Paramount Picture “Rhythm on the Range” in 1936.

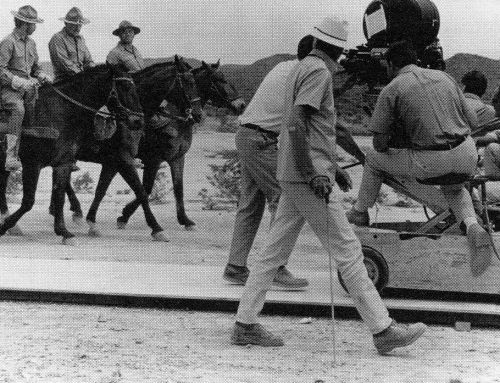

After the 1920s (and just beyond the scope of this blog series), other composers and arrangers grabbed the reins of cowboy music, for example: David W. Guion from Ballinger, Texas, and his series of “Texas Tunes” in the 1930s. Radio, movies, and later, television created the gallant “Singing Cowboy,” galloping into the West with America’s imagination. American music reached the trailhead of a truly American sound in the compositions of Aaron Copland, Ferde Grofé, Virgil Thomson, Roy Harris, and Dimitri Tiomkin.

After the 1920s (and just beyond the scope of this blog series), other composers and arrangers grabbed the reins of cowboy music, for example: David W. Guion from Ballinger, Texas, and his series of “Texas Tunes” in the 1930s. Radio, movies, and later, television created the gallant “Singing Cowboy,” galloping into the West with America’s imagination. American music reached the trailhead of a truly American sound in the compositions of Aaron Copland, Ferde Grofé, Virgil Thomson, Roy Harris, and Dimitri Tiomkin.

Leave A Comment