*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

Soundtrack of the American West

The Artist’s Playlists

So far, the Symphonies in our “Soundtrack of the American West” have explored the music of Native America and the songs of the cowboys. We have heard the actual sounds and music of the West, and also how this music was later interpreted, adapted, and arranged.

This time, we’ll take a different approach. Take a seat, unnoticed in a corner of each artists’ studio. But instead of listening to their paintings for the sounds of warriors, or cowboys in trouble, or windblown buffalo herds, we’ll hear the songs that Russell and Remington knew and mentioned in their letters and other writings. What follows are their playlists.

Charles M. Russell’s Playlist

A close-up of painting “Utica” showing Charles Russell leaning on a hitching post.

Charlie Russell, Banjo Player

Before he was an artist or even a cowboy, Charlie was a musician. John Taliaferro wrote about Charlie’s arrival in Montana in his biography Charles M. Russell: The Life and Legend of America’s Cowboy Artist (1996, p. 56):

In 1885, Charlie arrived back in Montana with his brother Ed, two years his junior, and his second cousin Chiles Carr, eight years older. Charlie gave Ed the tenderfoot’s rush, but also introduced him to the good families around the Judith Basin. The Russell brothers’ joint calling card seems to have been a banjo. For one reason or another, Charlie never mentioned his musical flair in the autobiographical recaps he gave to reporters in later years. But those with independent recollections of Charlie and Ed Russell saw a banjo in the picture. Ed and Charlie both played, recalled Eliza Walker, whose family moved into the Judith in 1882. Lollie Edgar remembered later that Charlie “always carried his Banjo with him. He knew all the popular songs.”

Who knew?? In honor of Charlie’s banjo playing, I’ve arranged some of his favorite cowboy songs in this blog with a banjo part.

“Cowboy Songs: and Other Frontier Ballads” by John A. Lomax, 1910

Charlie Russell, Singer

Charlie was also a singer. One of his first jobs on the range was night herder, or watching the horses and cattle. The position’s job description included singing to the herd. Austin Russell, Charlie’s nephew, described his performance – and singing – in his biography, C. M. R. – Charles M. Russell: Cowboy Artist (1957, p. 61-2):

The round-up foreman, Horace Brewster, had just quarreled with his night herder and fired him; and Cabler gave Charlie such a good “recommend” that he got the job. He might not have got it if anybody there had known who he was – that’s the kind of reputation his break with Pike Miller and his life with Jake Hoover had given him. Even as it was there were some doubts about him.

Old man True asked who the new night herder was, and Ed Older spoke up and said, “I think it’s Kid Russell.”

“Who’s Kid Russell?”

“Why,” said Ed, “he’s the kid who drew S. S. Hobson’s ranch so real.”

“Well,” says True, “if it’s Buckskin Kid, I’m betting that by morning we’ll be afoot!”

He didn’t mean Charlie would steal the horses but just sleep on the job and let them get away. In dry weather the wrangler who wants to take a nap will find some horse on the edge of the herd and kick him up – make him move over – and then the wrangler lies down on the ground the horse has got warm.

But Charlie didn’t sleep.

Though everybody called him “that ornery Kid Russell” he held the bunch, and at that time they had about four hundred saddle horses. And it wasn’t so easy to keep an eye at night on four hundred horses in a country where there wasn’t a fence between old Mexico and the Canadian line. This, you remember, was 1882, and Charlie was eighteen.

Charlie stayed with the outfit all summer, and next fall old man True hired him to night-herd beef, and for the best part of the next eleven years Charlie sang to the horses and cattle.

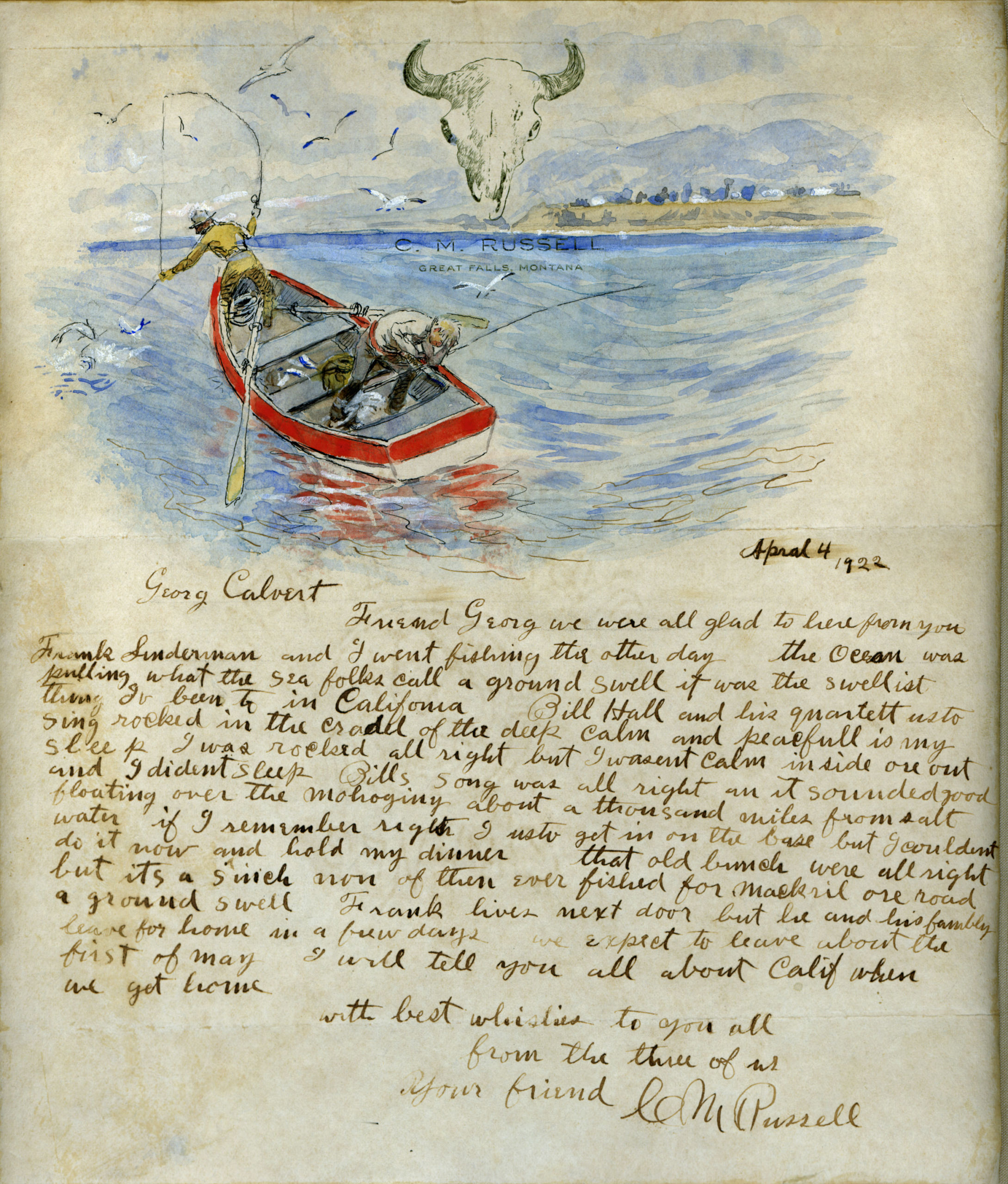

Apparently, Charlie had a deep bass singing voice, appropriate for singing “Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep” CMR letter to George Calvert, April 4, 1922 (Your Friend, p. 108-109):

…Frank Linderman and I went fishing the other day. The ocean was pulling what the sea folks call a ground swell. It was the swellist thing I’ve been to in California. Bill Hall and his quartet used to sing “rocked in the cradle of the deep, calm and peaceful is my sleep.” I was rocked alright, but I wasn’t calm inside or out, and I didn’t sleep. Bill’s song was alright and it sounded good floating over the mahogany about a thousand miles from salt water. If I remember right, I used to get in on the bass, but I couldn’t do it now and hold my dinner. That old bunch were alright, but it’s a cinch none of them ever fished for mackerel or rode a ground swell.

Charles M. Russell letter to George Calvert, April 4, 1922, Courtesy C.M. Russell Museum, 993.18.1001

Cowboy Songs, Real and “Fake”

Charlie referred to at least five known cowboy songs, including three in his posthumously published collection of stories, Trails Plowed Under: Stories of the Old West Trails (1927; Reprint – Lincoln, Neb: U Nebraska Press, 1990.)

“Sam Bass” and “The Texas Rangers” (arranged with banjo), were both mentioned in “Longrope’s Last Guard” (Trails Plowed Under, p. 205-7):

I tell you, there’s something mighty ghostly about sittin’ up on a hoss you can’t see, with them two little blue sparks out in front of you wigglin’ an’ movin’ like a pair of spook eyes, an’ it shows me the old night hoss is usin’ his listeners pretty plenty. I got my ears cocked, too, hearing nothin’ but Longrope’s singin’; he’s easy three hundred yards across the herd from me, but I can hear every word:

“Sam Bass was born in Injiana,

It was his native home,

‘Twas at the age of seventeen

Young Sam began to roam.

He first went out to Texas,

A cowboy for to be;

A better hearted feller

You’d seldom ever see.

…

“The lightnin’s quit now, an’ she’s darker than ever; the breeze has died down an’ it’s hotter than the hubs of hell. Above my voice I can hear Longrope. He’s singin’ ‘Texas Ranger’ now; the Ranger’s a long song an’ there’s few punchers that knows it all, but Longrope’s sprung a lot of new verses on me an’ I’m interested. Seems like he’s on about the twenty-fifth verse, an’ there’s danger of his chokin’ down, when there’s a whisperin’ in the grass behind me; it’s a breeze sneakin’ up. It flaps the tail of my slicker an’ goes by; in another second she hits the herd. The ground shakes, an’ they’re all runnin’.

“The Dyin’ Cowboy” (covered in the previous blog Cowboy Composers), is mentioned in “A Reformed Cowpuncher at Miles City”, (Trails Plowed Under, p. 152):

Although Montana’s gone dry, this special train from the north loaded with cowmen and flockminders don’t seem to feel the drouth none, and Miles City itself acts cheerful under the affliction. Teddy, though he ain’t drinkin’ nothin’ these days, admits to me on the quiet that just the little he inhales from his heavy-breathin’ friends has him singin’ ‘The Dyin’ Cowboy.’ He figures the ginger ale and root beer they’re throwin’ into ‘em must have got to workin’ in the bottles a little, judgin’ from the cheerful effect it has.

“Joe Bowers” was apparently one of Charlie’s favorite range songs (arranged here for Charlie’s banjo, plus harmonica). He saw Owen Wister’s play The Virginian in 1904 (see the previous blog, Song of the New Hero), but wasn’t especially impressed. He was dismayed that the play featured Wister’s “faked-up” cowboy song “Ten Thousand Cattle Straying”, instead of using a “real range song” like “Joe Bowers” (Austin Russell, C. M. R. – Charles M. Russell: Cowboy Artist, 1957, p. 99, 142-3):

“Joe Bowers” was apparently one of Charlie’s favorite range songs (arranged here for Charlie’s banjo, plus harmonica). He saw Owen Wister’s play The Virginian in 1904 (see the previous blog, Song of the New Hero), but wasn’t especially impressed. He was dismayed that the play featured Wister’s “faked-up” cowboy song “Ten Thousand Cattle Straying”, instead of using a “real range song” like “Joe Bowers” (Austin Russell, C. M. R. – Charles M. Russell: Cowboy Artist, 1957, p. 99, 142-3):

Later Charlie saw Bill [Hart] as Trampas in The Virginian and objected to his fake cowboy song, “In gambling hells delaying, Ten thousand cattle straying. Sons-of-guns is what I say, They rustled my pile, my pile away.” (In those days sons-of-guns was a very bold word to use on the stage.) Said Charlie, “Why didn’t you sing a real range song like Joe Bowers?”

“Don’t ask me,” said Bill, “ask the literary artist who wrote it. I’m just the poor villain who gets shot twice a day.”

“A Home on the Range” (also covered in the previous blog Cowboy Composers) is referenced in Charlie’s water color painting Thoroughman’s Home on the Range, 1897 (C. M. Russell Museum, Great Falls, Montana.)

Popular Songs

Jennie Lindsay

Flynn, Joseph. Paddy Shay. M. Witmark & Sons, New York, 1889. Notated Music. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/ihas.100006075/>.

In Austin Russell’s biography of his uncle Charlie, he stated that “except for a few range-songs … the only song I ever heard him sing was [“Paddy Shay”]… and the refrain, making his voice growl”. “Paddy Shay” was a “comic Irish song and chorus” written in 1889 by Joseph Flynn, and was billed as “Sheridan & Flynn’s Great Hit”.

Charlie also mentioned some popular songs in his letters and stories. The story “Night Herd” (Trails Plowed Under, p. 55-56) prominently features a popular song written in 1884 by Jennie Lindsay, who became famous eight years later when she performed “Daisy Bell” (“A Bicycle Built for Two”.) Jennie’s intent is ironically twisted in Charlie’s story.

Night Herd

This yarn, a friend of mine tells. I ain’t givin’ his name ‘cause he’s married, and married men don’t like history too near home, but I will say he’s a cowpuncher and his folks on his mother’s side wore moccasins. He tells me he’s holding beef for the TL out of Big Sandy. Him and another cowpuncher is on night guard. I’ll call this puncher “Big Man.”

“We’re holdin’ about fifteen hundred out of Big Sandy,” says Big. “We ain’t more than two miles from town, expecting to load. Where we’ve got ‘em bedded, you can see the lights of town, and once in a while I can hear singin’ and music. It’s a fine night. They’ve been on good grass all day and they’re laying good, so good my pardner says to me,

“Big, if you want to go to town for a while, I’ll hold ‘em all right.”

Says I, “I won’t be gone long, then you can take your turn.”

It ain’t long after till my hoss is at the rack, and I’ve joined the joymakers. They’re sure whoopin’ her up, singin’, and I get a little of that conversation fluid in me. I’m singin’ so good I wonder why some concert hall in Butte don’t hire me. The bartender is busy as a beaver – and the piano player’s singin’

Always take Mother’s advice;

She knows what is best for her boy.

Now, Charlie often interrupted his stories for suspenseful, dramatic effect – or just to roll a cigarette. So this may be a good time to pause and listen to one of the greatest hits of 1884, “Always Take Mother’s Advice” by Jennie Lindsay.

Now, Charlie often interrupted his stories for suspenseful, dramatic effect – or just to roll a cigarette. So this may be a good time to pause and listen to one of the greatest hits of 1884, “Always Take Mother’s Advice” by Jennie Lindsay.

Now back to the story. Big Man picks up where he left off, singing in the saloon about “taking Mother’s advice”…

And, of course, we’re all doin’ that. I’ve heard that song where a rattlesnake would be ashamed to meet his mother. But whiskey is the juice of beautiful sentiment.

A little while before I become unconscious, I’m shaking hands with a feller that I knowed for years, but never knowed he had a twin brother. The last I remember, I’m crawling my horse at the rack. Then the light goes out.

When I wake up I’m cold as a dead snake, and I’m layin’ on my belly in the middle of the herd. I’m feared to move ’cause many of this bunch are out of the brakes an’ are wild as buffalo and they’re mighty touchy. If I’d get up, this bunch would beat me to it, and when they’ve passed over, my friends would scrape me up with a hoe.

I can’t tell what time it is. It’s cloudy and I can’t find the [big] dipper. There’s one old spotted boy that I recognize; he’s a Seventy-nine steer. A few of them are standin’. One I see is wanderin’ around grazin’, but they’re mighty quiet. I’m gettin’ colder every minute. I’m wantin’ to smoke, but I dassn’t. I put my head on my arm and doze a little. … ‘Tain’t long. The next time I take a look, it’s breaking day.

“And where do you think I am?” says Big Man.

“In the middle of the herd,” says I.

“In the middle of the herd? In the middle of hell,” says he. “I’m laying in the center of the town dump. The steers that I been looking at are nothing but stoves, tables, boxes; all the discard of Sandy is there. The few that’s standin’ are tables. That spotted Seventy-nine steer that I know so well … is a big goods box. Them spots is white paper. The one I see movin’ around is my hoss. He’s the only live thing in sight.”

“I got a taste in my mouth like I had supper with a coyote. I ain’t quite dead, but I wish I was. From where I am, I can see Big Sandy, and from the looks, it’s as near dead as I am.”

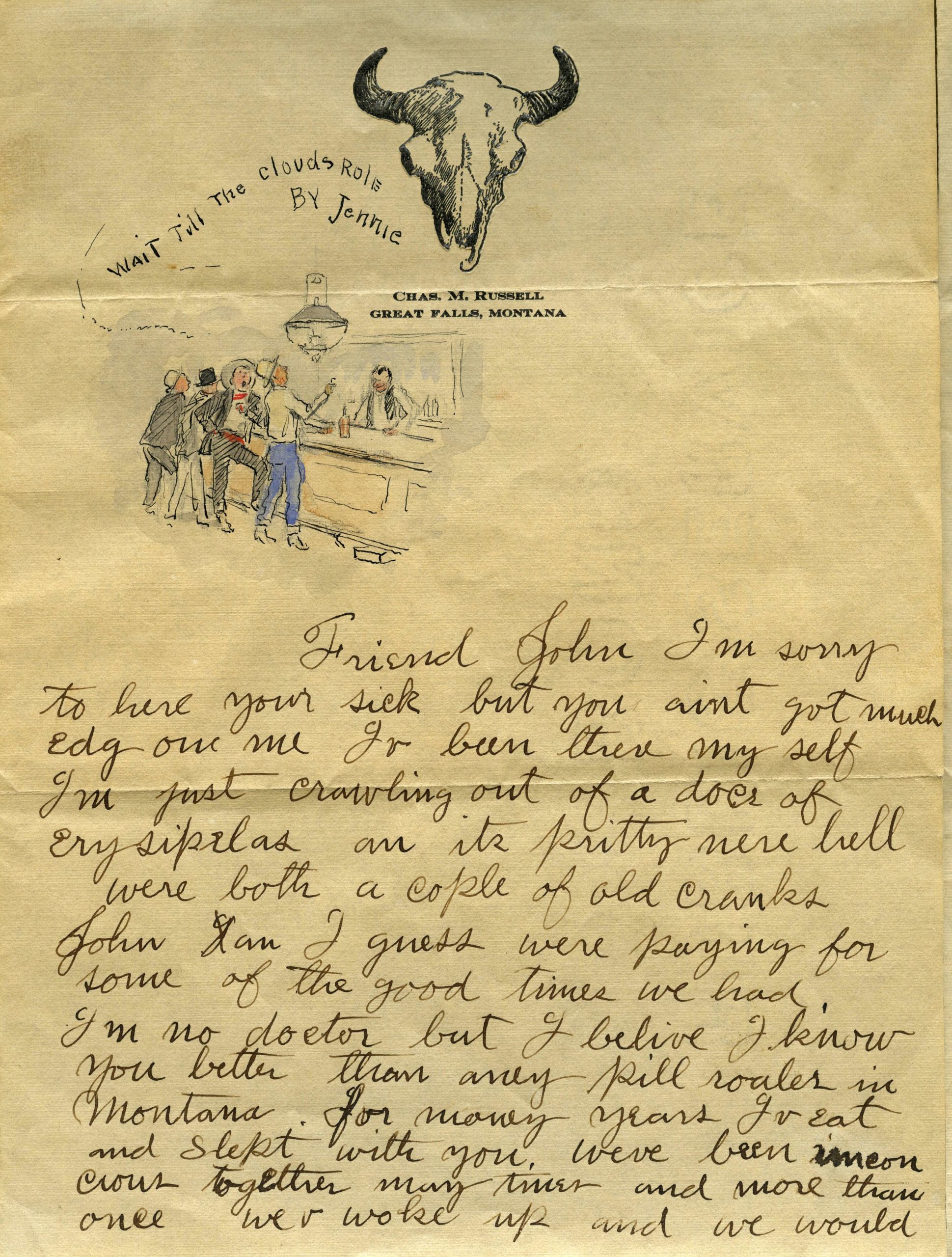

In 1915, Charlie wrote a letter to his friend John Matheson. Under his letterhead, he added a quick illustration with the two of them at a saloon bar singing the chorus, “Wait till the clouds role By, Jennie.” Written in 1881 by H. J. Fulmer and J. T. Wood, “Wait Till the Clouds Roll By” was one of the greatest sentimental hits of the 1880s and 1890s.

In 1915, Charlie wrote a letter to his friend John Matheson. Under his letterhead, he added a quick illustration with the two of them at a saloon bar singing the chorus, “Wait till the clouds role By, Jennie.” Written in 1881 by H. J. Fulmer and J. T. Wood, “Wait Till the Clouds Roll By” was one of the greatest sentimental hits of the 1880s and 1890s.

Charles M. Russell letter to John Matheson, 1915, Courtesy C.M. Russell Museum, 994.18.1001

Leave A Comment