Though Frederic Remington and Charles Russell are known today as fine artists, both worked as illustrators throughout their careers, creating paintings en grisaille, or in black & white, intended for reproduction to accompany stories and text. Our new exhibition – Remington and Russell in Black and White – features an array of both artists’ original greyscale masterworks paired with their counterparts printed in magazines and books.

During Remington & Russell’s time, illustrated magazines and books garnered wide popularity in the U.S., and thus earned the moniker The Golden Age of American Illustration, which began in the 1880s and lasted into the mid-twentieth century. This period of excellence in book and magazine reproduction developed from advances in technology that allowed for inexpensive yet high quality images to be reproduced easily and distributed to a wide audience.

Remington’s first commercial illustration appeared in an 1882 issue of Harper’s Weekly, but it was not until 1886 that his career as an illustrator took off. His work appeared in 142 books and 41 periodicals, most notably during his fifteen-year working relationship with the Harper Brothers, but also Scribner’s Magazine, Outing, Century Magazine, and Collier’s Weekly.

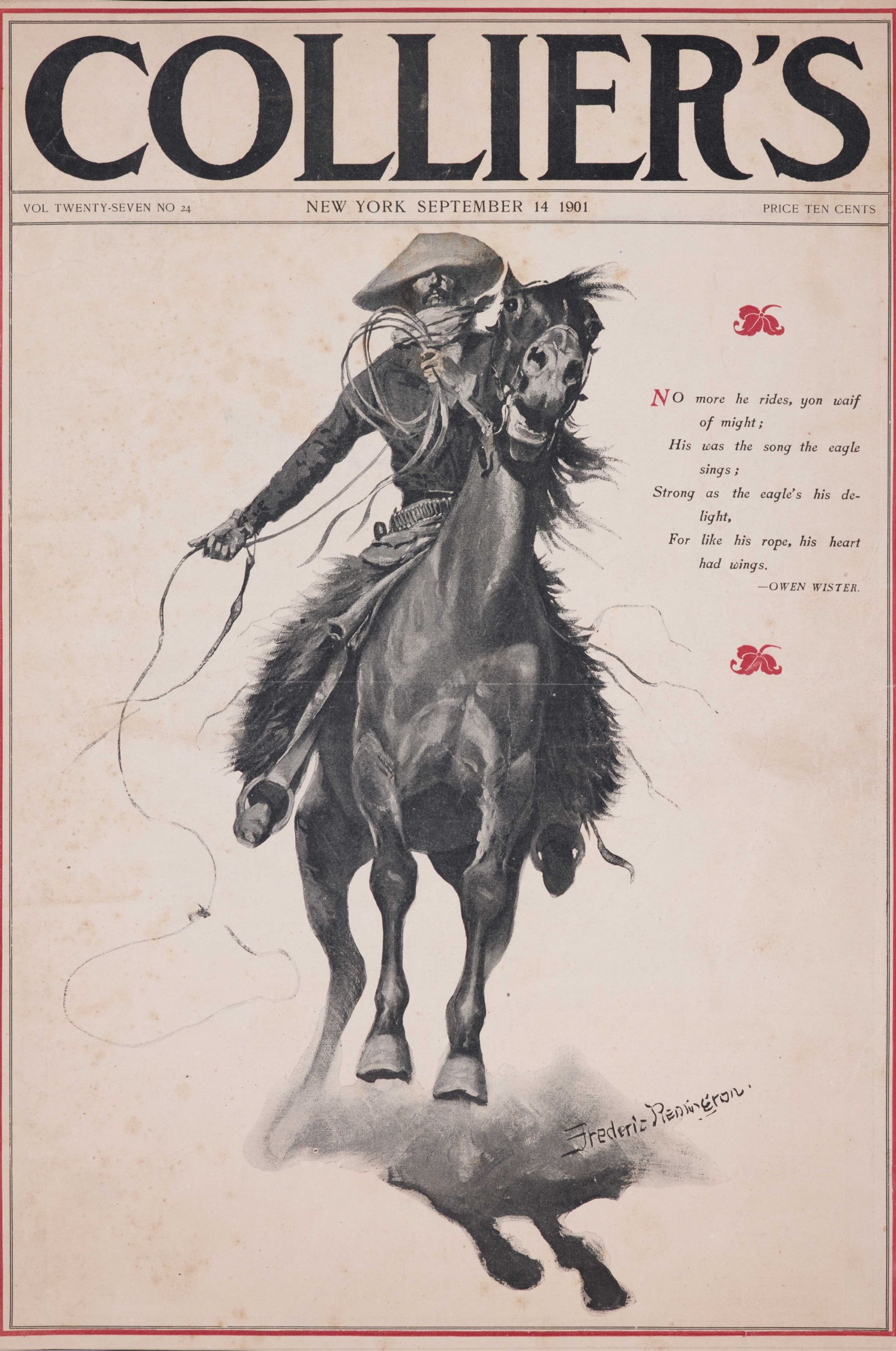

Remington most often created works en grisaille (or black and white) in oils, ink wash, and gouache that were reproduced by staff printmakers who worked for the publisher. For example, Remington’s black & white painting The Cow Puncher was made specifically to be reproduced as an illustration in Collier’s for its September 14, 1901 issue. In a reversal of his normal practice of creating an image to illustrate a story, here Remington created the image and then asked his friend Owen Wister to create a verse to accompany it for print. The white background perfectly accommodates the mast head and the open space around the image easily fits Wister’s verse.

Frederic Remington | The Cow Puncher | 1901 | Oil (black & white) on canvas | 28 7/8 inches x 19 inches

Frederic Remington, The Cow Puncher, Collier’s, September 14, 1901, cover

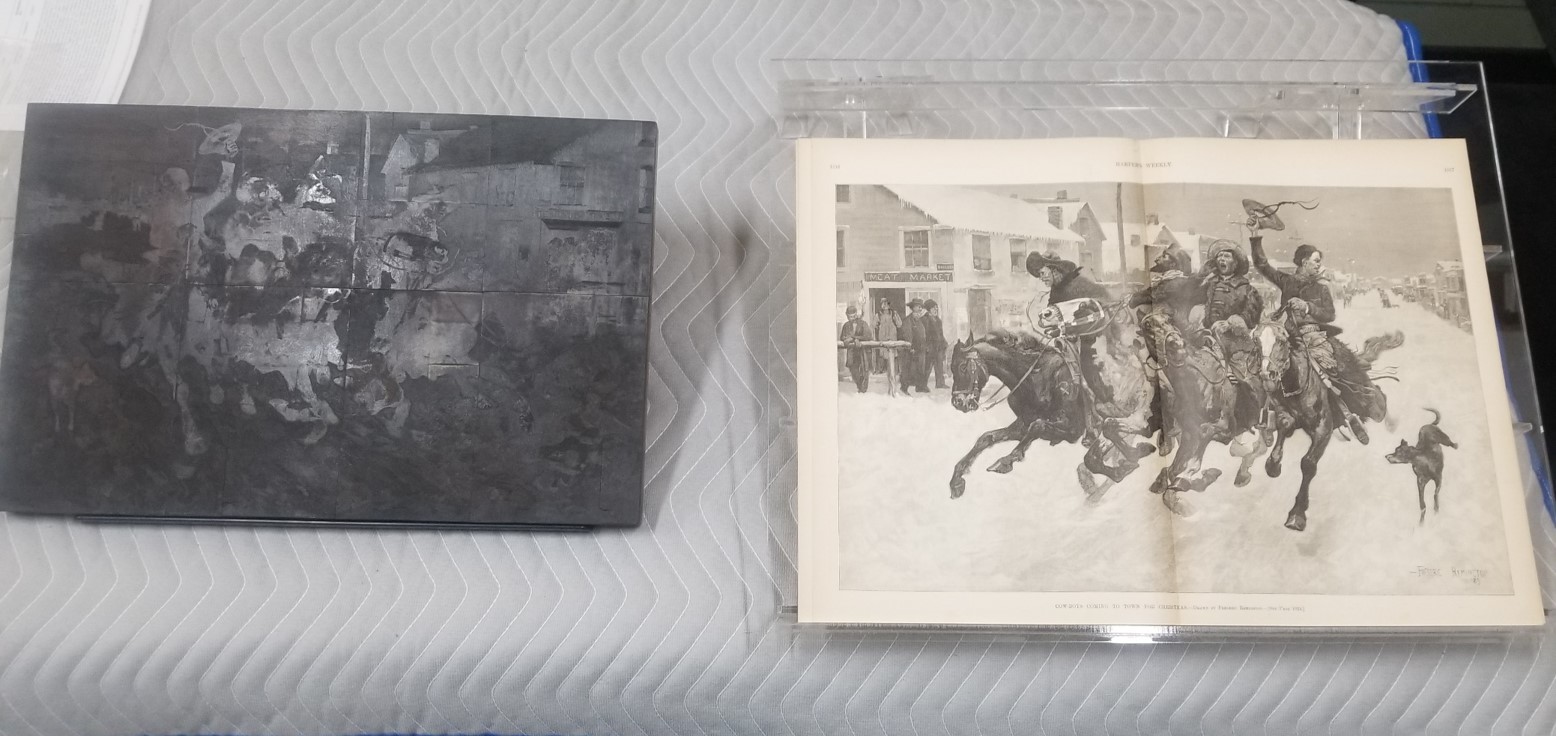

Another such example on view in the exhibit shows the wood engraving block and print that were used to reproduce Remington’s painting in the December 21, 1889 issue of Harper’s Weekly. Cow-Boys Coming to Town for Christmas was originally made as a 26 x 40” oil painting (now in a private collection). That work was then scaled down and transferred in reverse directly onto a series of interlocking small wooden blocks in order for the print to read correctly. A team of engravers would each receive a two-inch block to work on to speed up what would be a slow process for one person. An engraving tool was used to carve out areas that were to appear white on the illustration or cartoon. After all the blocks were completed, they were then screwed together to form the overall illustration and a finishing engraver would provide final touches to be sure the pieces were perfectly aligned. This completed wood block was then used as a “master” to stamp the illustration onto all the newspapers being printed.

Frederic Remington, Cow-Boys Coming to Town for Christmas, 1889, Wood Block & Magazine Print, Sid Richardson Museum, 2001.1.1.139

Like Remington, Russell’s first illustration was also featured in Harper’s in May of 1888. But apart from occasional book projects initiated by local Montana friends and acquaintances, Russell’s real output in illustration wouldn’t begin until after the turn of the century following his first trip to New York in 1904 with his wife and business manager Nancy. Then he found commercial success in illustrating, creating black and white works in oil, along with numerous watercolor and gouache, and pen & ink sketches until the end of his life in 1926.

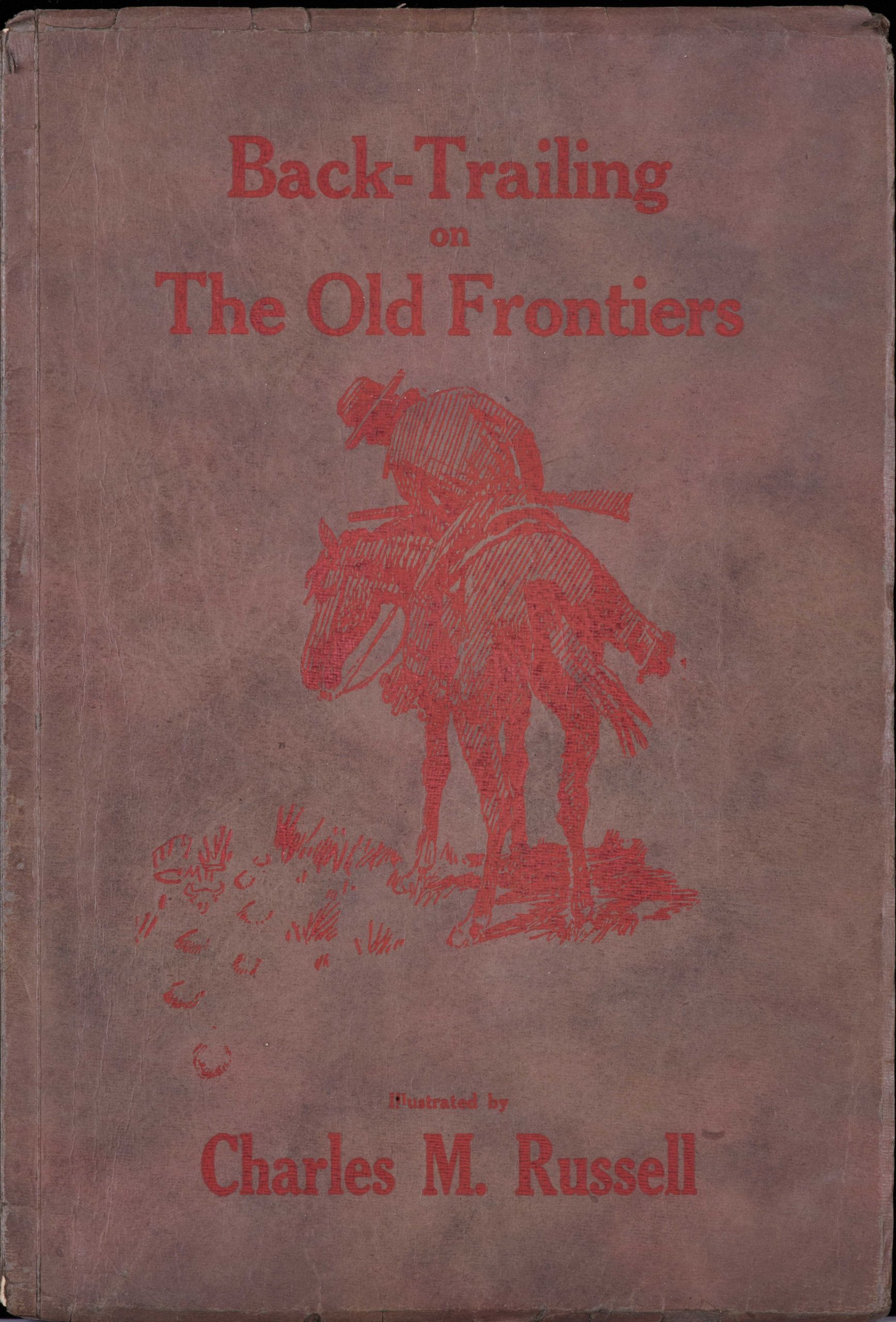

The exhibition features several of the drawings Russell made as illustrations for the series Back-Trailing on the Old Frontiers. Bill Cheely and Percy Raban of the Montana Newspaper Association (MNA) established a collaboration with Russell in 1921 wherein they would write a series of articles about the history of the Western frontier and Russell would create the illustrations. In all, 51 drawings for the series were distributed from March 1922 through February 1923. Cheely and Raban gathered 14 of the articles and published them in this book in 1922.

Back-Trailing on The Old Frontiers, Bill Cheely (1868-1939) and Percy Raban (1880-1959), Illustrated by Charles M. Russell, Great Falls, Montana: Cheely-Raban Syndicate, 1922

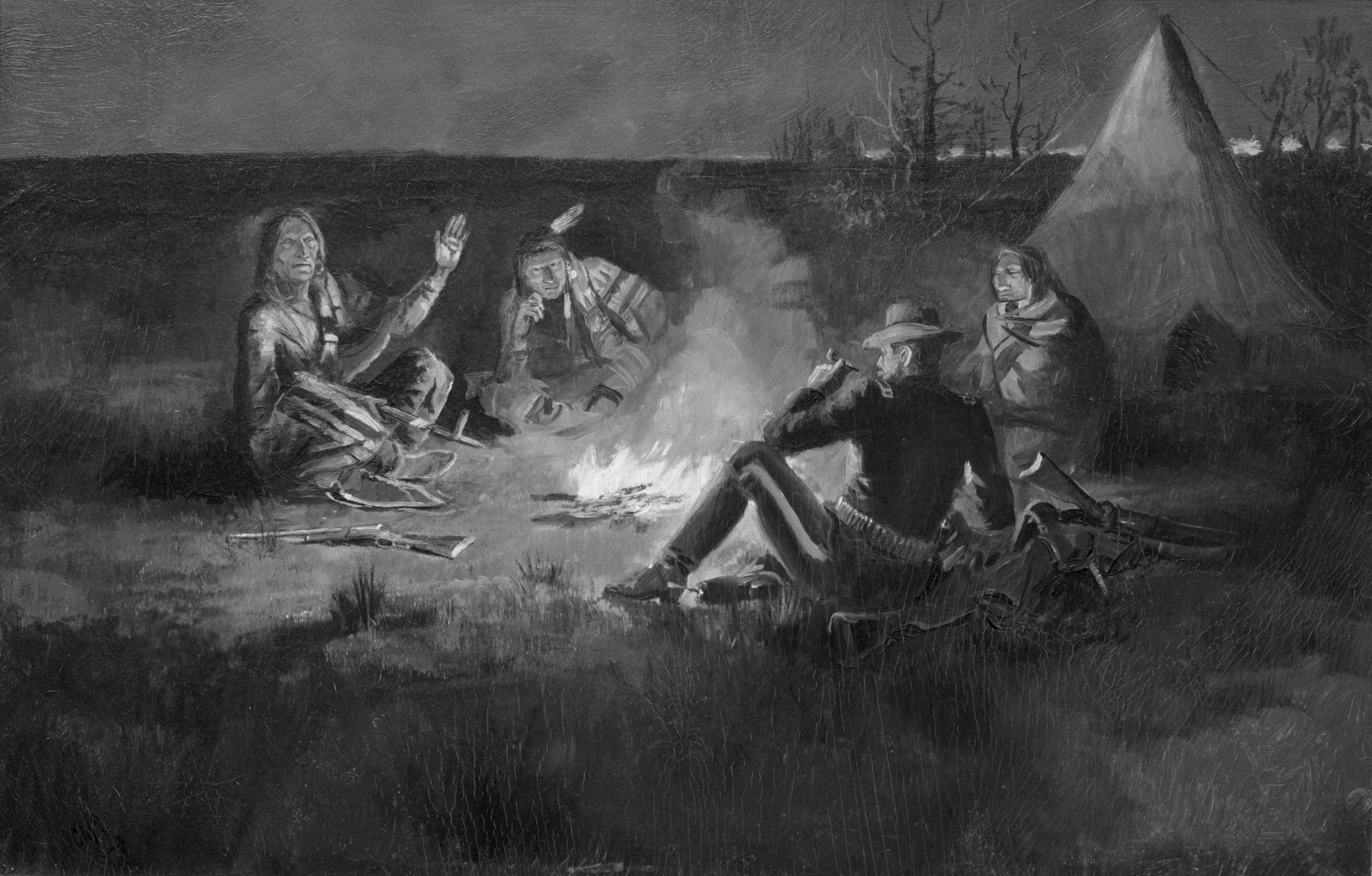

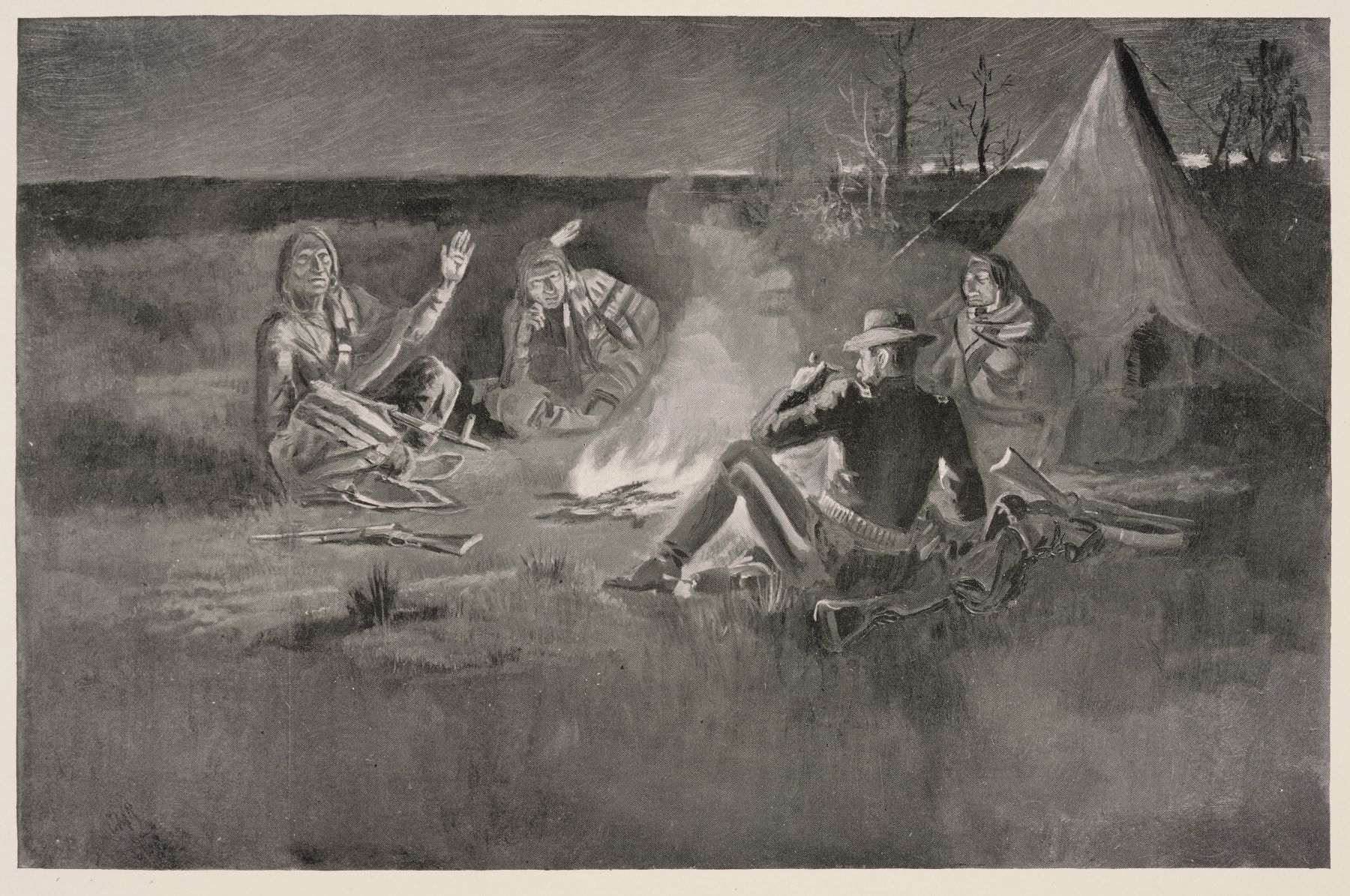

Another example of Russell’s ability to illustrate stories is seen in an artwork featured in the exhibit, An Evening with Old Nis-Sú Kai-Yo. This painting served as an illustration for the 1894 book, How the Buffalo Lost His Crown, transcribed by John H. Beacom. Beacom commissioned Russell to create eight illustrations (one oil and seven watercolors) for his project. The book recounts a story that Beacom was told by an old Blackfeet man named Nis-Sú Kai-Yo. Beacom must have found in Russell a kindred spirit as both men clearly possessed an empathy toward storytelling experiences they encountered and either wrote about or depicted from their interactions with Indigenous Americans at the close of the nineteenth century.

Charles M. Russell, An Evening with Old Nis-Sú Kai-Yo, ca.1894, Oil, The Petrie Collection

How the Buffalo Lost His Crown by John H. Beacom, Illustrated by Charles M. Russell, 1894, Amon Carter Museum of American Art

Though grisaille was traditionally used as the underpainting for a final work, Remington and Russell’s black and white artworks are finished works in themselves. Without the added complexity of color, viewers looking at Remington and Russell’s grisaille paintings have the opportunity to see how each artist developed his composition by building up shadows and highlights and the key details added to produce the desired contrast.

Leave A Comment