From classic Hollywood Westerns to sweeping contemporary epics, the American West on film is one of the most enduring visual languages in popular culture. The cowboys, outlaws, frontier families, and vast open landscapes feel instantly recognizable. But these images do more than tell stories. They shape how generations imagine American history.

As our current exhibition Cinematic West: The Art That Made the Movies examines how paintings inspired filmmakers and helped define the look of the Western, scholars like Dr. Mike Wise push us to look closer at the narratives beneath those images. Wise, a historian of the American West at the University of North Texas, studies Western films as historical documents, like windows into the values, myths, and cultural assumptions Americans bring to the past. His work reveals a powerful truth: when we watch Westerns, we’re not just watching stories about history. We’re watching stories about how Americans want to remember history.

The Frontier Myth on Screen

One of the most persistent ideas embedded in Western films traces back to Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous frontier thesis. Turner suggested that the experience of taming the frontier transformed European settlers into uniquely rugged, democratic Americans — a myth historians have long critiqued, especially for erasing Indigenous peoples and overlooking violence.

Yet the frontier myth continues to shape cinematic storytelling.

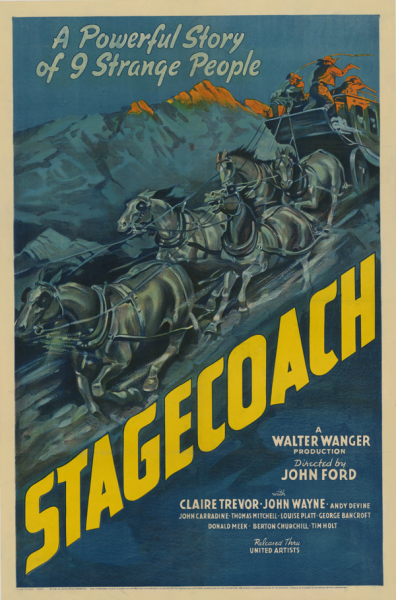

Early films like Cecil B. DeMille’s The Squaw Man (1914) embody this transformation narrative: an English aristocrat becomes a more authentic, tougher version of himself in the West. Later films, such as John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939), cemented the Western hero’s journey — danger, moral testing, and personal reinvention — as a central American storyline.

Through these stories, audiences absorbed the notion that the West was a place where identity could be reforged and character revealed. Even when historians moved beyond Turner’s ideas, Western films kept the myth alive.

Stagecoach Movie Poster, 1939, Lithograph, Poster collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Violence and the “Defensive Conquest” Myth

Pekinpah (far right) directs the opening scene of Wild Bunch

Wise also identifies what he calls a defensive conquest narrative, or the framing of white American violence as justified, necessary, or inevitable.

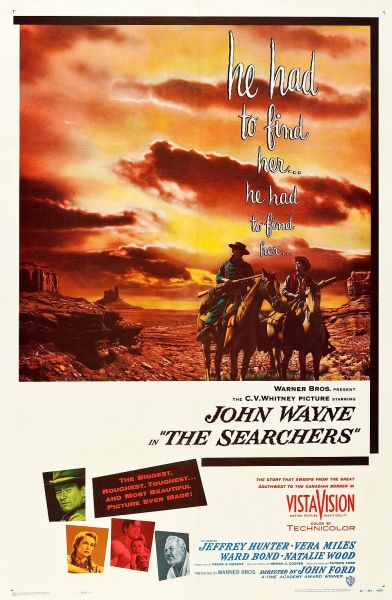

Films like The Searchers (1956) dramatize this tension. John Wayne’s character, an “unreconstructed Confederate,” embarks on a violent quest coded as rescue and defense. The film’s beauty — its monumental landscapes, its technical brilliance — overshadow the brutality embedded in the story.

Revisionist Westerns of the 1960s and ’70s began pushing back. Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch (1969) portrayed violence not as righteous but as destructive and self-annihilating. Later, films such as Django Unchained (2012) confronted the legacy of slavery head-on, refusing the selective memory that shaped earlier films.

Through shifts like these, the Western genre reveals changing American conversations about power, justice, and the costs of conquest.

US theatrical release poster for the film The Searchers (1956) by Bill Gold

Nature as Teacher, Mirror, and Character

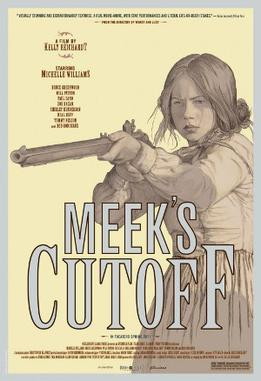

Meek’s Cutoff (2010)

In more contemporary films, Wise notes a growing trend: the landscape as a central figure. Directors use vistas the way painters once did, not simply to set a scene, but to shape meaning.

Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain (2005) uses mountain landscapes to evoke authenticity, intimacy, and the tension between internal truth and social expectation. Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff (2010) transforms the Oregon desert into a psychological terrain of fear, uncertainty, and survival, where muffled dialogue and minimalism mirror the limits of the settlers’ worldview. Even Westworld (2016), with its blend of science fiction and Western tropes, uses sweeping landscapes to explore questions about humanity, artifice, and perception.

In these works, nature is no longer a backdrop. It’s an agent shaping the story.

Why Westerns Still Matter

As Dr. Mike Wise makes clear, Westerns are valuable not because they offer accurate accounts of the past, but because they reveal how Americans have chosen to interpret that past. Films encode ideas about race, gender, citizenship, land use, violence, and national identity. Sometimes explicitly, sometimes through omission. They show how certain narratives became mainstream, how others were minimized, and how cultural memory gets shaped in the process.

Just as the artists featured in Cinematic West helped define the visual language of the West through paint and composition, filmmakers reinforced and expanded those same ideas on screen. Both mediums influence how viewers understand concepts like the “frontier,” “civilization,” “wilderness,” and “belonging,” often in ways that outlast the historical realities they depict.

Studying these films through Wise’s analysis allows us to see the genre as evidence of the stories Americans have valued, evidence of the perspectives that dominated Hollywood for decades, and evidence of the assumptions that shaped popular understandings of the West. Rather than accepting Westerns as straightforward representations, Wise’s approach encourages us to treat them as cultural artifacts that reveal how historical narratives are constructed, repeated, challenged, and changed over time. If you’d like to take a deeper dive into these themes and hear Dr. Wise’s full discussion, be sure to check out the recording of his recent lecture, “Reel History: How Western Films Shape Our View of the American Past.”

Leave A Comment