During his time as a regular illustrator, apart from his documentation of the American Indian Wars and the Spanish American War, Frederic Remington was often sent out on assignment to capture the daily routines of the cavalry. In 1893, he traveled out west to Yellowstone National Park to write and illustrate an article about the 6th Cavalry patrols in the park to prevent poaching, including the dwindling bison herd that was supposed to be protected there.

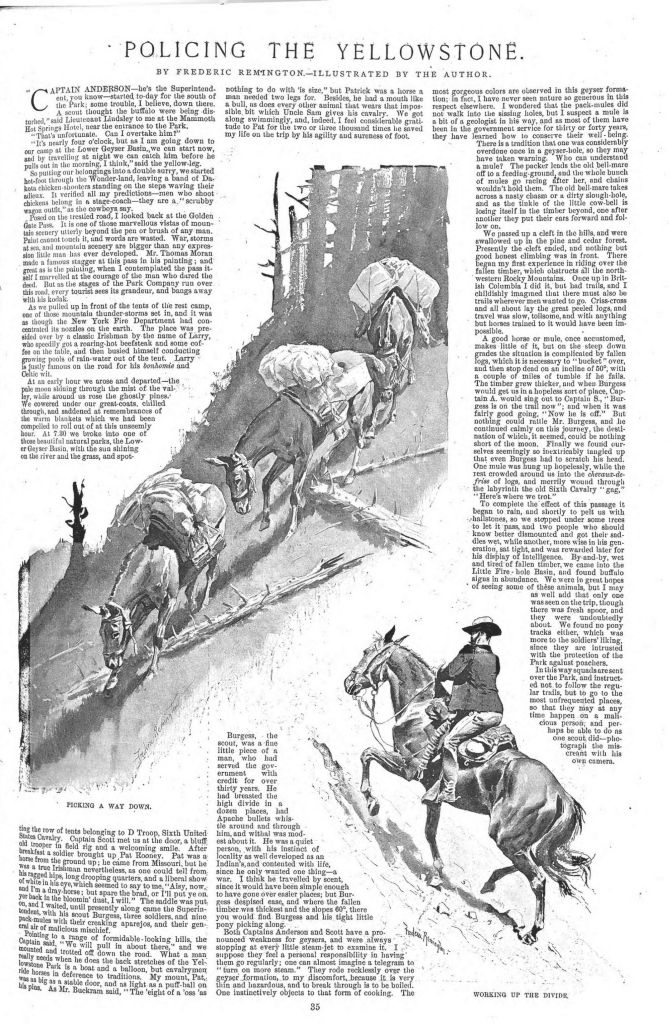

“Policing the Yellowstone,” Frederic Remington, Harper’s Weekly, January 12, 1895

Remington’s article appeared in the January 12, 1895 issue of Harper’s Weekly titled, “Policing the Yellowstone.” The journey began from Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel near the entrance of the park. Through his writing and accompanying illustrations, Remington takes us through the back stretches of Yellowstone, stopping now and then to take in its beauty through his senses. Like folks today, Remington stood in awe as he looked at the Golden Gate Pass.

“It is one of those marvelous vistas of mountain scenery utterly beyond the pen or brush of any man. Paint cannot touch it, and words are wasted.”

As such, Remington grumbled about the tourist of the late 19th century who “bangs away with his kodak,” – not too dissimilar from the notorious smartphone visitors of today – attempting to capture an ounce of the park’s grandeur.

During the trip, Remington and his crew passed by geysers and noted his companions’ weakness for such attractions, as they “were always stopping at every little stream-jet to examine it. I suppose they feel a personal responsibility in having them go regularly; one can almost imagine a telegram to ‘turn on more steam.’” Can’t you just see that showing up in a one-star Yelp review today?! “Visited Old Faithful. Not enough steam.” Remington, for his part, appreciated the geysers warming effects on nearby water streams, “by the aid of which I ‘policed my face,’ as the soldiers call shaving.”

Eventually, Remington and the men reached their destination: Little Fire-hole Basin. They found evidence of bison in the area but no big sightings. Likewise, there were no tracks from recent poachers. What a relief! By traveling off trail into the more unfrequented places of the park, the cavalry anticipated either encountering “a malicious person” or, by leaving tracks from the expedition where the poacher can see, discourage illegal activity.

At that time the Yellowstone herd was estimated to be around 400. By 1902, the herd numbered around 25. Even if the officers had found poachers during Remington’s visit, they would have had no power to prosecute, and would simply have expelled them from the park. However, following Remington’s visit, The Lacey Act was passed in Congress in 1894, allowing park administrators to punish poachers.

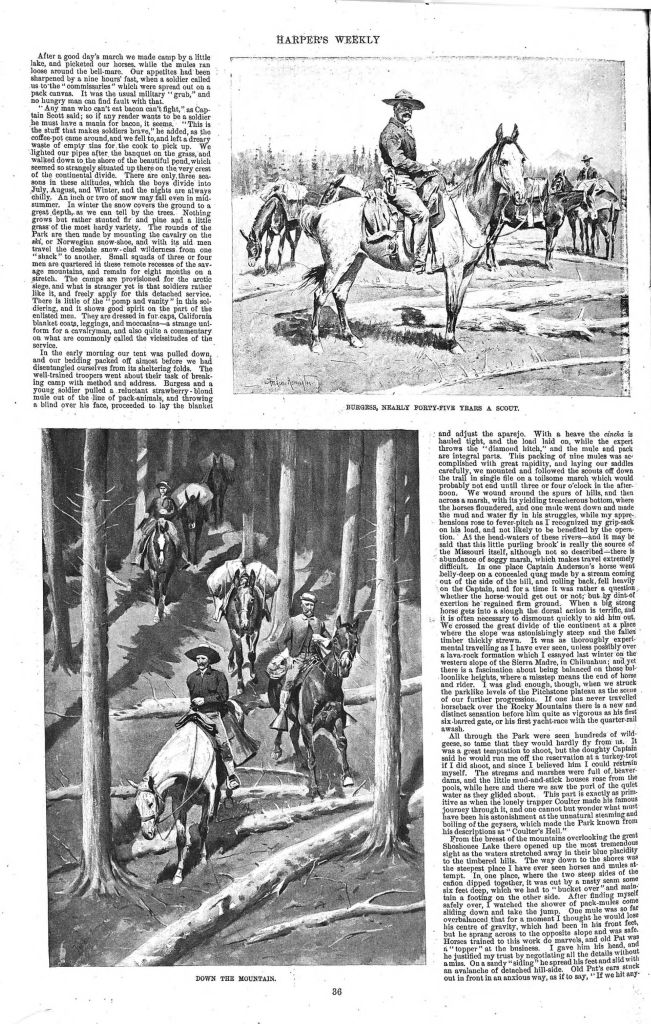

After he returned to New York from Yellowstone, Remington wrote to his friend, the journalist Poultney Bigelow, about the ride over the mountain with the 6th Cavalry, “One would not believe where a horse will go.” Scaling the mountain and, in particular, coming down the steep slopes littered with fallen logs, must have made an impression on Remington as he dedicated four out of seven of the article’s illustrations to traversing the terrain.

“Policing the Yellowstone,” Frederic Remington, Harper’s Weekly, January 12, 1895

Frederic Remington, Picking a Way Down, ca. 1893, ink wash and gouache on paperboard, Private Collection

In Picking a Way Down, featured in our current exhibit, the carefully delineated pack mules stand in contrast against a dark, roughly painted forested mountain landscape. They are shown hopping over the logs as they make their way down the slope. In the printed page layout in Harper’s, the diagonally oriented drawing is paired with another illustration, Working up the Divide. Along with the cropped text, the images create a dynamic composition across the page, adding further visual interest to both word and image.

Whether in words or images, what’s clear through Remington’s article is how much he treasured Yellowstone:

“Americans have a national treasure in the Yellowstone park, and they should guard it jealously. Nature has made her wildest patterns here, has brought the boiling waters from her greatest depths to the peaks which bear eternal snow, and set her masterpiece with pools like jewels. Let us respect her moods, and let the beasts she nurtures in her bosom live, and when the man from Oshkosh writes his name with a blue pencil on her sacred face, let him spend six months where the scenery is circumscribed and entirely artificial.”

Leave A Comment