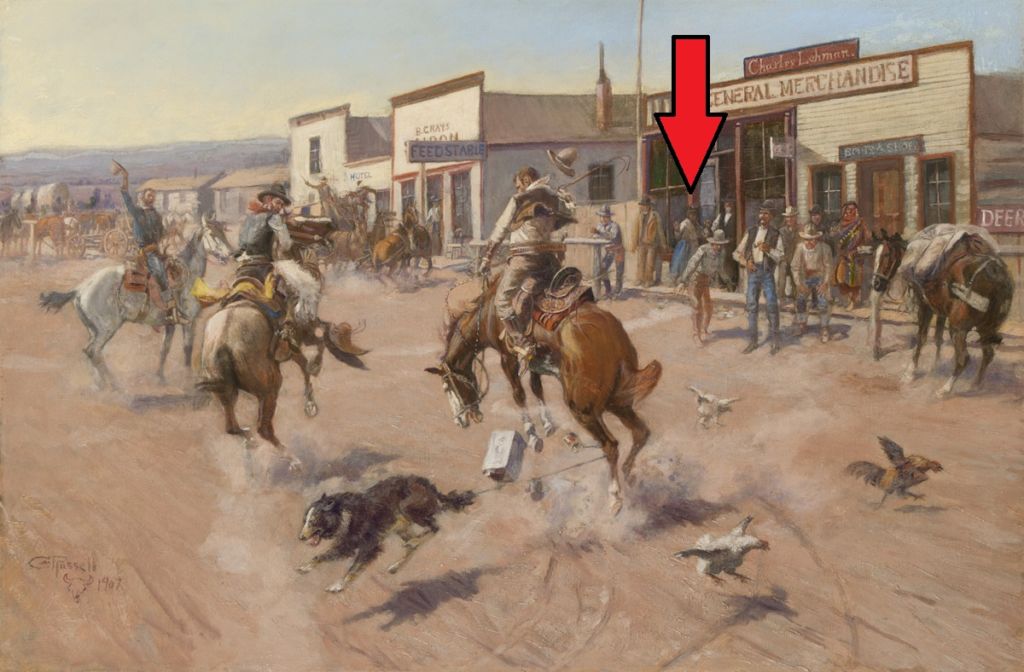

In 1907, Charlie Russell paid tribute to Montana resident, Millie Ringgold, in his painting “Utica.” A musical person, Millie often played songs while drumming her empty five-gallon coal oil can, which can be scene prominently in Russell’s painting. In honor of Black History Month, join us as we follow the story of a freed slave, her favorite song, and the first great cautionary tale of the oil age. The following article was researched and written by SRM docent, S. Mark Clardy.

Millie Ringgold

Millie Ringgold was born a slave in Maryland in about 1845. After the Emancipation Proclamation, she went to Washington, D.C., at age 20 to work as a nurse and servant, and then went west with an army general. When he was transferred back east, she stayed in Montana, bought a pair of condemned army mules and a wagon, loaded up with supplies and a barrel of whiskey at Fort Benton, and then headed for a boom town called Yogo with $1,600. She established a hotel, restaurant and saloon and began working her two mining claims. Like most gold mine claims, it didn’t turn out very well.

She was known as being very musical, using whatever she had – mouthharp, hand saw, washboard, dishpans. The miners bragged that she could make more music with an empty five–gallon can, than most people could playing a piano.[1] Her favorite songs were “Coming Thro’ the Rye” and “Coal Oil[2] Johnny on a Bum Bum Solree,”[3] undoubtedly accompanied by vigorous drumming on her 5-gallon can.

That’s where the story starts getting interesting musically. I suspect the story would also interest Sid Richardson, Amon Carter, and the other oil tycoons of the 20th century.

In 1868, shortly after the Civil War, an Irish actor named John Brougham wrote a play, published in San Francisco, called “The Lottery of Life.” (The phrase apparently meant that to be born British was to “win the lottery of life,” i.e., to be born at the top of the international heap.) One of the characters in the play was a man who struck it rich with an oil well and became a profligate spender. Most likely, this was the character in the play who had won “the lottery of life.” His name was “Coal Oil Tommy,” and he sang a song of the same name:[4]

“Coal Oil Tommy” by John Brougham

I’ve come from Pennsylvania, some city life to see,

And you may bet your boots, I’ll have the biggest kind of spree.

With my pockets stuffed with greenbacks and a skin full of old rye,

Amongst the oyster cellar swells a jolly boy am I.

Chorus: And Coal Oil Tommy is my name, Coal Oil Tommy is my name,

Good for any game tonight my boys, Good for any game tonight my boys,

Coal Oil Tommy is my name, Coal Oil Tommy is my name,

Good for any game tonight my boys, Hi! Ten strike set ‘em up again.

Upon the road I drive the very spiciest of drags

Behind a pair of thoroughbred four thousand dollar nags

That didn’t allow me never to take no one else’s dust.

I’ll sell them both for oat meal if they weren’t always first.

In the doings of the fancy, I’m up to everything,

And I’d go a thousand miles to see the heroes of the ring.

If you want to bet your money, you’ll find I’ve been to school,

And for any sum you like I’ll go my pile on Mike McCool.

“The Lottery of Life” was first shown on June 8, 1868, at Wallack’s Theater in New York.[5] One of the actors was named B. T. Ringgold[6]. Could the newly freed Millie have seen or heard of the play before moving to Washington? It’s unknown whether B. T. Ringgold played the role of Coal Oil Tommy, but supposing he did, could a recently freed slave, possibly in need of a surname, have “borrowed” the last name of the actor portraying a character whose lifestyle she could only dream about?

It appears that Millie’s lyrics got a bit jumbled phonetically. The phrase “bum bum solree” (“soiree”?) could be a corruption of the line “biggest kind of spree.” After all, when lyrics are forgotten or misunderstood, people usually make something up to fit the tune.

There was also a popular tendency to change the song name from “Tommy” to “Johnny” because the public immediately identified the “Coal Oil Tommy” character in the song and play with a real life person who had been making East coast headlines for a year or two, and not in a good way. In fact, the two stories are so similar that the real “Coal Oil Johnny” probably inspired Brougham’s play, earning it the designation of a “contemporaneous play,” i.e., reflecting contemporary events. This modern fable, complete with a “moral of the story,” began to unfold after the end of the Civil War.

John Washington Steele

Being born in 1843, John Steele was a contemporary of Millie Ringgold. He was adopted from a poorhouse by a farmer and his wife at Oil Creek, Venango co., Pennsylvania, the site of the country’s first oil boom. But the farmer died, leaving elderly “Widow McClintock” with their adopted son. In 1864, she burned to death in a wood stove conflagration, when a splash of coal oil went awry. So at age 21, Johnny (by now with a wife and two children) inherited the farm, and its couple of producing oil wells. He had never made more than $40 per month, but immediately began raking in $3000 a day as a coal oil tycoon. Unfortunately, he got tangled up with a gold-digger companion who convinced him to spend wildly. Within three years, he lost his entire fortune when the wells stopped producing. A proverbial prodigal Johnny returned to his family, and ended up as a teamster making $50 a month.

His sprees between 1864 and 1867 were the stuff of legend, and filled many newspaper columns, even after his death in 1921. The public appears to have quickly fused John Brougham’s 1868 character “Coal Oil Tommy” and the legendary “Coal Oil Johnny” that they read about in the newspapers. By 1881, the fabled name of “Coal Oil Johnny” had become the common term to mean anyone who inherited or rapidly acquired vast wealth, spent it foolishly, and ended up penniless. In 1884, there were two race horses, one named “Coal Oil Tommy” and the other named “Coal Oil Johnny.”[7] After that, it appears that “Coal Oil Johnny” reigned supreme as the preferred term for a profligate spender.[8]

His sprees between 1864 and 1867 were the stuff of legend, and filled many newspaper columns, even after his death in 1921. The public appears to have quickly fused John Brougham’s 1868 character “Coal Oil Tommy” and the legendary “Coal Oil Johnny” that they read about in the newspapers. By 1881, the fabled name of “Coal Oil Johnny” had become the common term to mean anyone who inherited or rapidly acquired vast wealth, spent it foolishly, and ended up penniless. In 1884, there were two race horses, one named “Coal Oil Tommy” and the other named “Coal Oil Johnny.”[7] After that, it appears that “Coal Oil Johnny” reigned supreme as the preferred term for a profligate spender.[8]

Sadly, Millie Ringgold’s life followed the path of “Coal Oil Johnny” on a smaller scale. She went broke in her various endeavors, thinking that her gold claims would eventually make it big. Instead of gold, she kept finding little blue rocks which were tossed back into the mining stream. Many years later, these blue rocks became known the best sapphires in the world. Millie was finally reduced to subsisting on frozen rutabagas until the Sheriff got her some jobs working for local families. He intended to take her to a poor house, but independent minded Millie fought that.

Sadly, Millie Ringgold’s life followed the path of “Coal Oil Johnny” on a smaller scale. She went broke in her various endeavors, thinking that her gold claims would eventually make it big. Instead of gold, she kept finding little blue rocks which were tossed back into the mining stream. Many years later, these blue rocks became known the best sapphires in the world. Millie was finally reduced to subsisting on frozen rutabagas until the Sheriff got her some jobs working for local families. He intended to take her to a poor house, but independent minded Millie fought that.

She died December 2, 1906. The following year, Charlie Russell painted “A Quiet Day in Utica.” As a tribute to Millie, he placed her standing once again on the boardwalk in front of Lehman’s General Store, along with other recognized locals. They’re all watching a bucking horse, spooked by a dog darting across the dusty street. Both horse and dog are terrified by the clanging and drumming of cans tied to the dog’s tail, prominent among them, Millie’s empty five-gallon coal oil can.

Charles M. Russell | Utica (A Quiet day in Utica) | 1907 | Oil on canvas | 24 1/8 inches x 36 1/8 inches

[1] Moser, Cathy. “Yogo City or Bust” Big Sky Journal. Spring-Summer 2009.

[2] “Coal oil” was the term used for kerosene, which lit the night in the days before Edison.

[3] “Millie Ringgold’s Fascinating Story” 31 December 2009. See web link in References.

[4] Brougham, John (lyrics), and Alfred Lee (music). “Coal Oil Tommy.” No date; play performed in NY in 1868.

[5] “Amusements: Dramatic, Wallack’s Theatre” New York Times, June 9, 1868.

[6] “Amusements this Evening: Wallack’s Theatre” New York Times, July 20, 1868.

[7] Chester, Walter T. Complete Trotting and Pacing Record of 1884, p 844, col 3.

[8] Numerous New York Times articles 1881 to 1896.

B.T. Ringgold is indeed listed as playing the role of Oil Tommy in The Lottery of Life. See new wikipedia article I just started! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lottery_of_Life

Thank you for sharing, Milo!

I understand that this article is nearly a year old but in discussion of the song Coal Oil Tommy, I think it is worth noting the tune was not an original composition but rather an adaptation of the British music hall song Champagne Charlie, a song with a similar theme of a boasting spender. This song would stay popular in the UK through the Second World War where there would be a film made of it starring Tommy Trinder. However relevantly to this article the song crossed back into the realm of African American music when a blues version of it was recorded by the blues man Blind Blake or perhaps someone else under his name, there is some controversy. However either way the same melody that Mollie Ringgold was playing before the turn of the century was still being played in the 1930’s by the same musical tradition as her but through an entirely different path.

How interesting! I’ll be sure to pass this along to our docent who researched and wrote this article and see if he’s familiar with these details. I appreciate you sharing your knowledge!