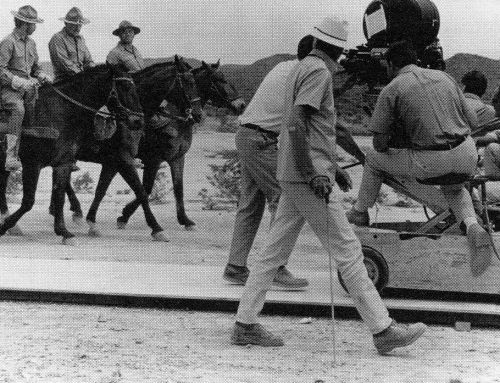

“She Wore a Yellow Ribbon,” 1949, Lithograph, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, OK

When most people imagine a Western film, a lone cowboy rides into view: stoic, dust-covered, and armed with grit. But not all Westerns follow this familiar trail. In a lesser-known but equally dramatic corner of the genre, the cowboy steps aside, and in his place rides the United States Cavalry. These soldiers, clad in iconic blue uniforms, brought a new dimension to Western cinema—one rooted in spectacle, military might, and a complicated legacy of American expansion.

Filmmakers like John Ford turned their lens to the cavalry in classics such as Fort Apache (1948) and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), weaving tales of honor, duty, and conflict on the American frontier. But these films didn’t invent the cavalry drama. They inherited it. Decades before audiences flocked to the theater, Americans were captivated by outdoor Wild West shows, where cavalry reenactments played out on dirt stages under open skies. Around the same time, artists like Frederic Remington were capturing these moments with oil, bronze, and ink.

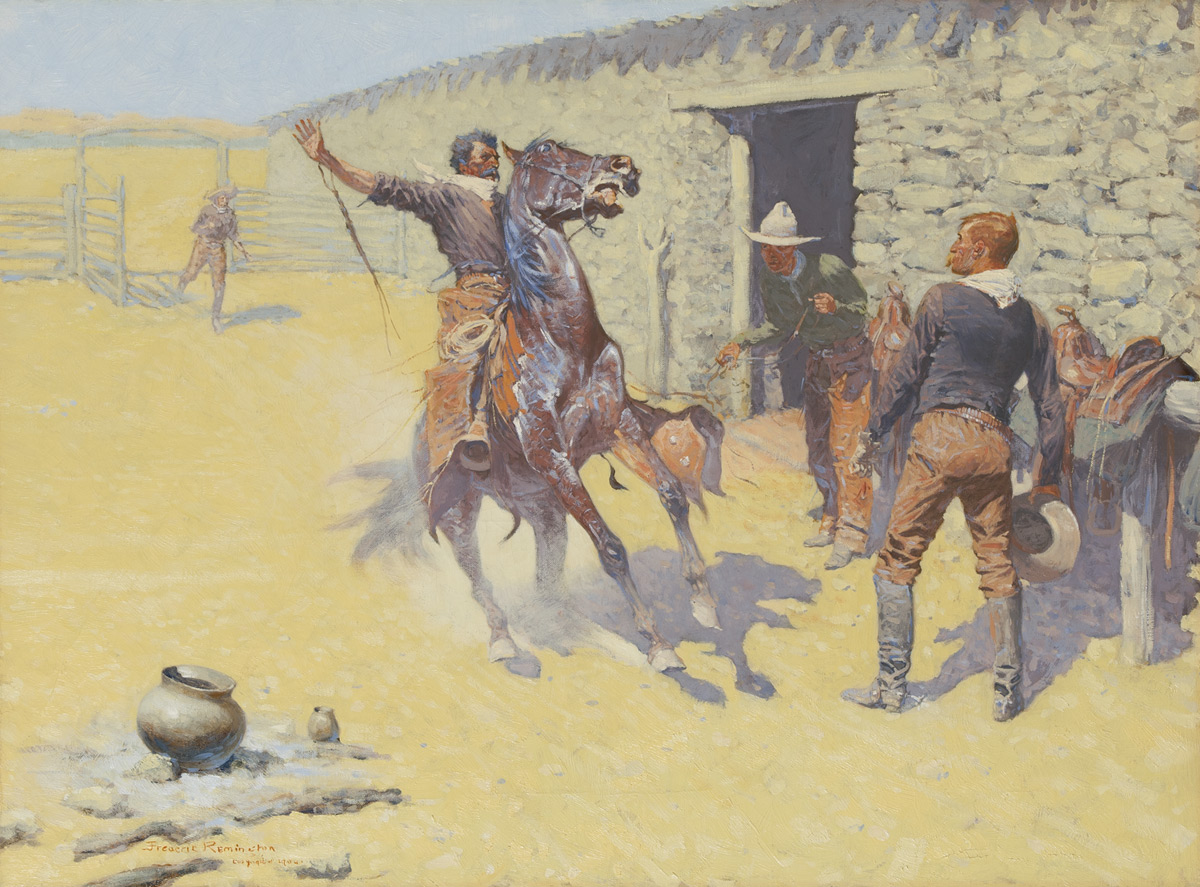

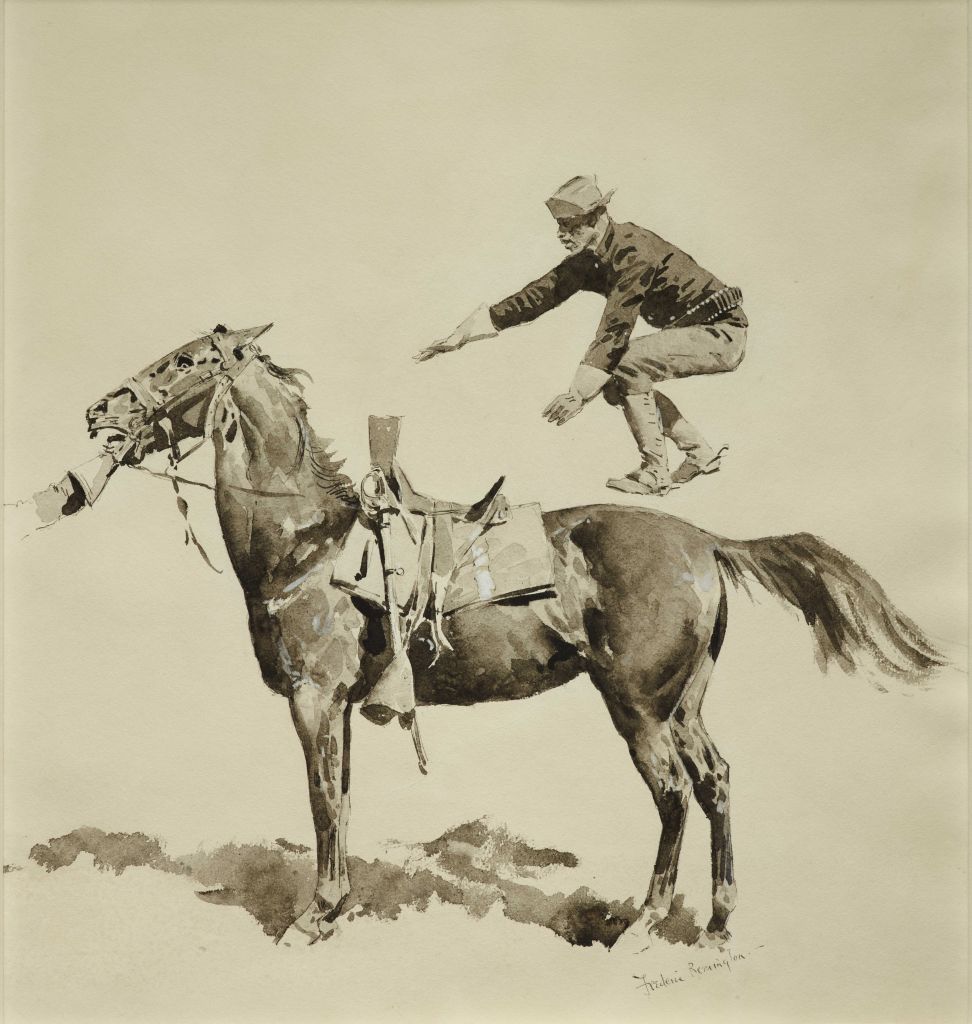

Remington, an artist as much in love with motion as with myth, was drawn to the cavalry’s tension-filled narrative. On assignment for publications like Harper’s Weekly, he portrayed mounted soldiers in scenes brimming with cinematic energy. In his work, cavalrymen brace for unseen enemies, make desperate last stands, and even defy gravity in daring feats of horsemanship. These weren’t just illustrations. They were action scenes frozen in time, pulsing with color, drama, and danger.

Frederic Remington, Among The Led Horses, 1909, Oil on canvas, 27 x 40 inches

So impactful were Remington’s visions that director John Ford—himself a master visual storyteller—insisted his cinematographer, Winton Hoch, study Remington’s artworks closely. Remington’s paintings and sculptures served as both aesthetic guideposts and historical references, shaping the look and feel of Ford’s cavalry films. The dusty reds, sun-bleached yellows, and deep frontier blues found in Remington’s palette translated seamlessly to Ford’s Technicolor landscapes, helping to define the visual language of the cavalry Western.

Visitors to our current exhibition can experience this lineage firsthand. Standing before Remington’s dynamic scenes of horse and rider, one can almost hear the thunder of hooves and the cries of conflict that later echoed across the silver screen. It’s a vivid reminder that before there were Westerns in theaters, there were Westerns in paint. And the drama of the American cavalry has always been as much about how we tell the story as the story itself. But how we tell that story matters. The images that thrilled audiences then and now do not exist in a vacuum. They are built on real histories of violence, power, and survival that continue to shape how we understand the American West today.

Frederic Remington, The Apaches!, 1904, Oil on canvas, 25 x 30 inches

The same images that made cavalry stories so visually compelling have also helped shape a contested historical memory. From pivotal engagements like the Battle of the Greasy Grass/Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 to the tragic Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890, cavalry operations shaped both the landscape of the American West and the lived realities of Indigenous peoples. This dual legacy continues to challenge museum educators and historians seeking to contextualize these narratives.

Cavalry history is further complicated by the experiences of the Buffalo Soldiers—the African American troopers of the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments—who served with distinction despite facing profound racial discrimination. Their bravery and service reveal the ways in which military and racial hierarchies intertwined, highlighting the complex social and ethical dimensions of westward expansion.

Frederic Remington, Jumping on to a Horse, ca. 1896, ink wash drawing on paper, Private Collection

Today, as contemporary filmmakers, game designers, and digital artists continue to revisit and reimagine the Western genre, they echo Remington’s visual language, intentionally or not. Shows like Yellowstone or video games like Red Dead Redemption carry the same visual DNA: sweeping landscapes, morally complex characters, and tension between order and chaos. And with ongoing national conversations around history, representation, and the mythologizing of the American West, these works prompt us to reflect not just on what we see, but how and why we see it. The West, after all, has always been as much a product of imagination as of history.

Leave A Comment