Cowboys are back.

From streaming sensations like Yellowstone and 1883 to Oscar-nominated films like The Power of the Dog, the American West is once again galloping through our cultural imagination. But this isn’t the first time the West has captured our collective attention—nor is it a new story. Long before cameras rolled in Monument Valley or grizzled heroes rode into dusty towns, the mythology of the West was painted in oils and sculpted in bronze. Artists like Frederic Remington and Charles Russell didn’t just illustrate the frontier, they invented the visual language that would define it for generations to come.

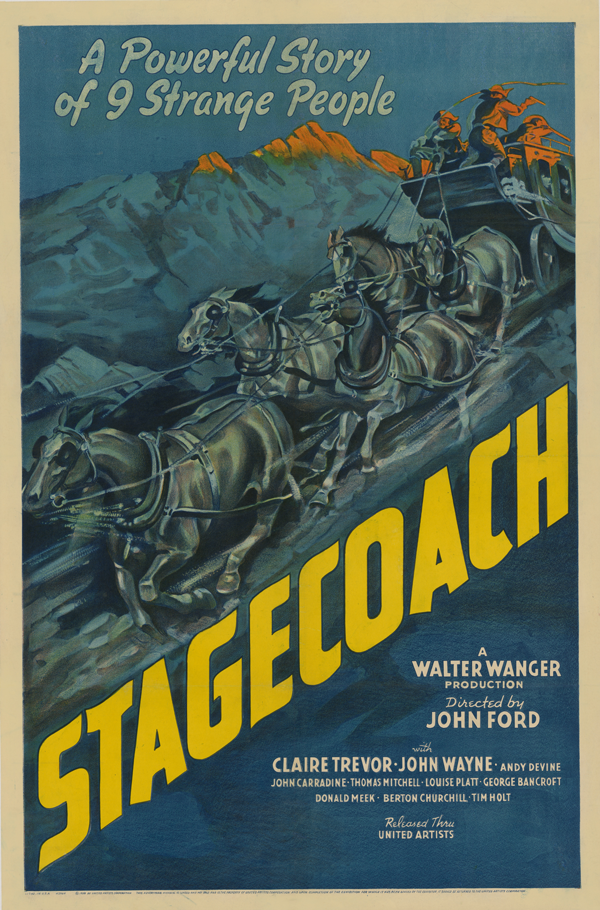

At the Sid Richardson Museum, our new exhibition The Cinematic West: The Art That Made the Movies invites visitors to explore how fine art influenced the early days of Western cinema—and continues to shape the way we tell stories about the West today. By pairing works from our permanent collection with rare silent film footage, vintage movie posters, and Hollywood memorabilia, this exhibition offers a fresh perspective on how American identity has been imagined and reimagined through both brushstroke and camera lens.

Stagecoach Movie Poster, 1939, Lithograph, Poster collection, Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Frederic Remington, A Taint On the Wind, 1906, Oil on canvas, 27 1/8 x 40 inches

Painting the West Before It Was Filmed

The Western genre has long served as a mirror for America, reflecting both our ideals and our contradictions. Its origins stretch back to the late 19th century, when artists like Remington and Russell began capturing what they saw (or imagined) in the vast frontier: open landscapes, stoic cowboys, clashes of cultures, and the drama of survival on an unforgiving land. Their paintings weren’t documentary; they were aspirational, romantic, and mythic.

These same themes would become the foundation of early Western films. As cinema emerged in the early 20th century, filmmakers turned to familiar visual tropes—wide-open spaces, lawmen and outlaws, heroic stands at high noon—many of which were lifted directly from the canvases of these artists.

One notable example on view in the exhibition is Remington’s A Misdeal (1897). This tense, dimly lit poker scene was so evocative that it found its way into not one but two Hollywood films. Originally owned by actor Douglas Fairbanks—one of early cinema’s biggest stars—the painting also passed through the hands of legendary movie producer Hal Wallis, best known for Casablanca (1942) and True Grit (1969). Fairbanks wasn’t just a collector; he was a friend of Charles Russell, who, along with his wife Nancy, spent winters in Southern California mingling with stars like Will Rogers and William S. Hart. In the early 1920s, the line between fine art and film was more than blurred—it was collaborative.

Frederic Remington, A Misdeal, ca.1897, Oil on canvas, Private Collection

Douglas Fairbanks, Charles Russell, and Nancy Russell, Bain News Service, ca.1920-1925, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division; George Grantham Bain Collection

Buffalo Bill: The Original Showrunner

But the roots of the Western story go deeper still—to the live-action spectacles of the late 1800s. When Buffalo Bill Cody launched his Wild West show in 1883, he set the template for Western storytelling that would dominate American popular culture for over a century.

Remington and Russell were just beginning their careers when Cody took his show on the road (and across the Atlantic). Their artworks developed in tandem with Cody’s performances, each influencing the other. Where Cody offered drama and choreography, Remington and Russell gave texture, nuance, and permanence.

Charles M. Russell, Breaking Up the Ring (Breaking Up the Circle), 1900, Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper, 19.5 x 29.375 inches

It’s no coincidence that many classic Western film tropes—like the circling of wagons under attack—originated not on the prairie, but in the arena. Buffalo Bill’s reenactments, like the dramatized version of Custer’s Last Stand, became etched into the American imagination. And though they were often historically inaccurate, they helped solidify a version of the West that filmmakers would later bring to the screen. Cody even tried his hand at filmmaking with The Indian Wars (1913), a rare silent film featured in our galleries.

Today, when audiences watch a Western, they’re often engaging with storytelling DNA that dates back to Cody’s arena and the brushstrokes of Remington and Russell.

Landscapes as Characters

In the Western genre, the land is never just a backdrop—it’s a main character. Director John Ford, who filmed many of his classics in Monument Valley, once said, “The real star of my Westerns is the land.”

This idea is explored in-depth in the exhibition, especially through the contrasting landscapes painted by Remington and Russell. Remington, who spent much of his life in the Northeast, imagined the West as an unforgiving place—his barren, sun-drenched settings are harsh, dramatic, and stripped of sentimentality. Russell, rooted in Montana, infused his works with affection and familiarity. His landscapes—of the Missouri River valley, the Belt Mountains, and Square Butte—are full of vitality, a testament to his lived experience and deep connection to the land.

Their visions helped define how audiences expect the West to look on screen. Just as Monument Valley became synonymous with John Ford’s vision, Russell’s Montana scenes became a visual shorthand for authenticity, long before the term became a buzzword.

Still from Stagecoach, Chronicle, 1939, Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo

Why the Western Still Resonates Today

So why does the Western endure?

In a time of rapid change and shifting ideas about American identity, the Western continues to offer a canvas for our hopes, fears, and ideals. The stories we tell about the West—whether in art, film, or television—are often stories about self-reliance, justice, freedom, and survival. They’re about people navigating vast, untamed spaces and grappling with moral complexity. And perhaps most of all, they’re about reinvention—of the land, the self, and the nation.

Modern Westerns like Yellowstone and The Power of the Dog may challenge older tropes, offering more nuanced portrayals of Indigenous peoples, frontier women, and the costs of conquest. But they’re also working within a visual and narrative tradition that began over a century ago—with artists like Remington and Russell sketching and painting the very myths that would later animate the screen.

Still from She Wore A Yellow Ribbon, Chronicle, 1949, Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo

Frederic Remington, The Unknown Explorers, 1908, Oil on canvas, 30 x 27.25 inches

Step Into the Story

The Cinematic West: The Art That Made the Movies invites visitors to trace this fascinating arc—from art to film, from myth to modernity. By placing paintings, sculptures, and illustrations alongside early silent film footage and vintage movie posters, the exhibition reveals how art laid the groundwork for one of America’s most enduring genres.

Whether you’re a lifelong fan of Westerns or a newcomer curious about the stories we tell ourselves, this exhibition offers a chance to reconsider what the West means—then and now.

Come explore the art that made the movies—and continues to shape the stories of America!

Leave A Comment