*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Kay and Velma Kimbell Chair of Art History TCU School of Art, and guest curator of SRM’s special exhibit Another Frontier: Frederic Remington’s East.

On a recent return flight to DFW, the Airbus in which I was a passenger encountered, in the pilot’s words, “moderate turbulence” (most of us onboard would not have used such an understated description). Sitting next to a window over an engine I was able to hear not only its powerful thrusts, but also the sounds of the mighty winds buffeting the plane. While I was listening to roiling weather outside, the title of one of Frederic Remington’s great paintings, The Howl of the Weather, currently on view in Another Frontier: Frederic Remington’s East, came to mind as an apt expression of what I was experiencing. You never know how or when art is going to intersect with life!

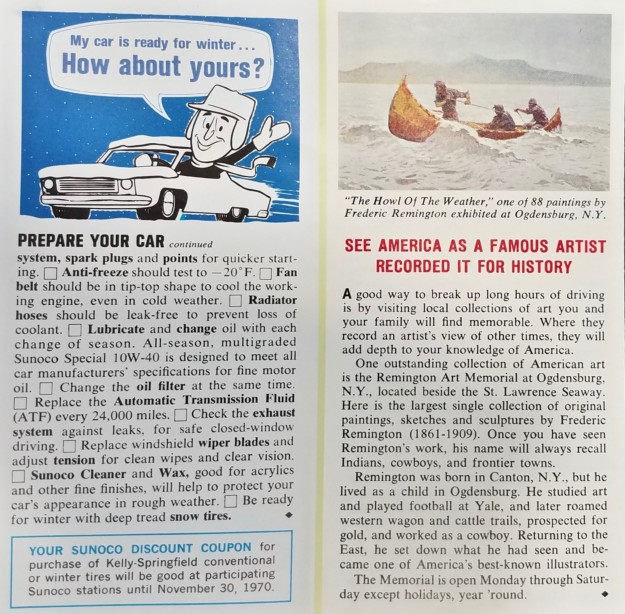

Frederic Remington | The Howl of the Weather | ca. 1905 | Oil on canvas | Frederic Remington Art Museum, Ogdensburg, NY

The Howl of the Weather depicts the determination and urgency to find safe harbor. Two men are attempting to balance and control the birch canoe during a squall as strong winds and rough waves threaten to outrace the craft, which could lead to water swamping it. The perilousness of the situation is reinforced by the woman and child huddled together holding on in the center of the canoe. Remington’s inspiration for this painting may have been a story he had published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in August 1896, where he included the phrase “the howl of the weather.” Prior to those words occurring in the text, the narrator had described canoeing on Lake Champlain, where “the wind blew at our backs. The waves rolled in restless surges, piling the little canoes on their crests and swallowing them in the troughs. The canoes trashed the water as they flew along, half in, half out . . .”[1]

The Howl of the Weather’s setting is undetermined. When the artist entered it for copyright on January 18, 1906, it was described as “Birch canoe with two Indian men and a woman in the waves of a lake.” When P. F. Collier and Son entered an additional copyright on February 11, 1907, the description given was of “a canoe going along a river. . . . The water is very rough.” I like to think that Remington purposely kept the location vague, in part to maintain focus on the struggling canoe and the dynamic brushwork that conveys so well the rough water. Also, not delineating the background in detail contributes to the painting’s sense of the sublime.

The sublime was an aesthetic concept proposed in the eighteenth century, most famously in Edmund Burke’s A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origins of the Beautiful and the Sublime (1757). This British publication had a major impact on shaping the rise of American landscape painting in the early nineteenth century. It contrasted the clarity and order of the beautiful to the vastness, obscurity, and irregularity associated with the sublime. Further, the sublime revealed a sense of terrifying power (not actual but imagined), which made it more emotionally intense than the beautiful. For viewers of The Howl of the Weather, but not the figures depicted in it, the scene is sublime. By expressing an image of nature that is limitless, shadowy, and filled with awe-full energy and noise, Frederic Remington’s The Howl of the Weather continued the tradition of the sublime into the twentieth century.

1970 Sunoco Brochure

Moving from the sublime to the seemingly ridiculous, I want to share pages from a brochure I came across while engaging in research in the St. Lawrence University Special Collections. As I am always on the lookout for examples of works of art being used in our everyday visual culture, I was struck to come across a reproduction of The Howl of the Weather in a 1970 Sunoco gas company pamphlet (“Sunoco-grams” for Sunoco customers) about preparing your car for winter. When I first saw these pages, I regarded the inclusion of Frederic Remington’s painting as quirky. But now I think that maybe Sunoco’s connection between winterizing your car and The Howl of the Weather is really not so very different from my conjuring up the painting while being bumped around in an airplane. Powerful art can function in many ways.

[1] Frederic Remington, “The Strange Days that Came to Jimmie Friday,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 93 (August 1896): 416

Leave A Comment