From galloping riders to sweeping desert vistas, the American West as we know it was shaped as much by the artist’s brush as by the filmmaker’s lens. Our current exhibition, The Cinematic West: The Art That Made the Movies, explores how Western art influenced—and was influenced by—the silver screen. The exhibition invites us to reflect on how painters and filmmakers alike helped craft a mythology of the frontier, a mythology that persists in American popular culture. But behind the romanticized imagery of cowboys and Indigenous figures lies a more complicated story, especially when it comes to how Native people have been represented on film.

Liza Black, Picturing Indians: Native Americans in Film, 1941–1960 (University of Nebraska Press, 2020)

In classic Hollywood Westerns, Native Americans often appeared as background figures in someone else’s epic, their identities flattened into tropes. But historian and Cherokee Nation citizen Dr. Liza Black invites us to reconsider these portrayals. In her recent lecture for the Sid Richardson Museum and her book Picturing Indians: Native Americans in Film, 1941–1960, Dr. Black uncovers the lived realities of Native actors and extras working in mid-20th-century cinema, individuals who were both participating in and resisting the myths they were asked to embody.

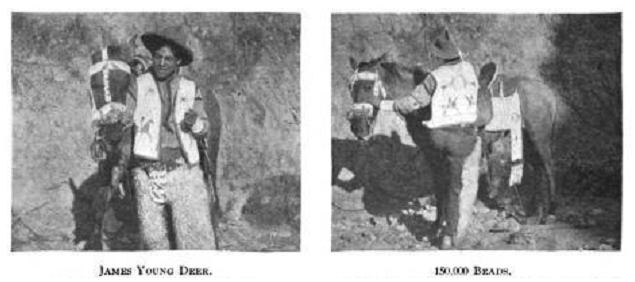

James Young Deer, ca. 1910, believed to be the first Native American filmmaker/producer in Hollywood.

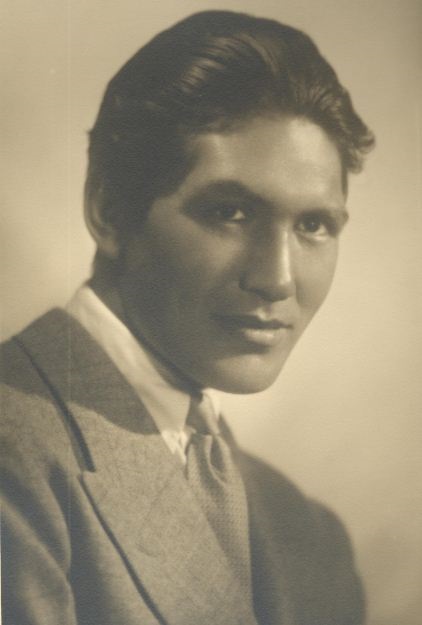

Ray Mala, 1933, a prominent Alaska Native actor. Courtesy “The Mala Collection” University of Alaska, Anchorage

The “Authentic Indian”: A Construct, Not a Character

Hollywood sought “authenticity” in its portrayals of Native people, but its definition was rooted not in truth, but in audience expectation and commercial formulas. Native actors were often cast based on their ability to fit a predetermined visual mold: braided hair, stoic demeanor, “exotic” speech patterns. This idea of authenticity was not Indigenous but invented, crafted by non-Native screenwriters, directors, and technical advisors.

In one striking example, Navajo actors working on John Ford’s films in Monument Valley were often coached—ironically—by white consultants on how to “act Indian,” despite already being Native themselves. This reflects a broader trend: even when Native people were present, their own voices were filtered or overwritten to serve Hollywood’s mythic narrative.

Clayton Moore as the Lone Ranger and Jay Silverheels as Tonto, 1956

Work, Not Romance: Film as Livelihood

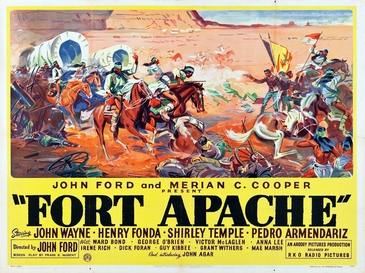

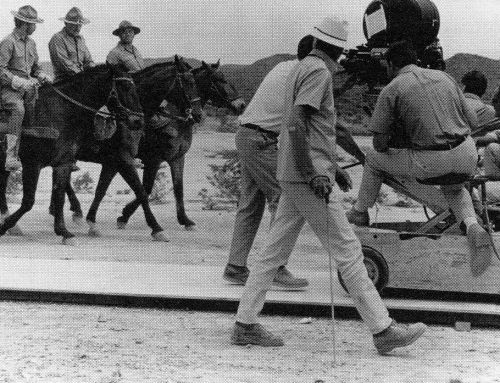

While mainstream narratives often romanticize or vilify Native roles in film, Dr. Black shifts the lens to labor. In films like Fort Apache (1948) and She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), many of the Native actors—often Navajo—were recruited from nearby reservations. Involvement in Western films was rooted less in cultural expression and more in economic necessity. Extras, riders, and language speakers accepted roles for the paycheck, navigating typecasting and indignity while seeking opportunity.

Rather than focusing only on how they were depicted, Dr. Black asks us to consider what it meant to work in film as a Native person in the 1940s and ’50s. These were not just characters on a screen but individuals with bills, children, and dreams; people whose participation in film reveals both compromise and agency.

Subversion and Survival

Even within the limits of Hollywood’s scripts, Native performers found ways to inject meaning, critique, and cultural specificity. Whether through a glance, a gesture, or the inclusion of an unscripted phrase in their own language, actors created space for Indigenous presence within a framework that often denied their humanity.

Dr. Black challenges us to consider the difference between visibility and voice. Native people were highly visible in classic Westerns, but rarely were they allowed to speak on their own terms. Yet in small, often unnoticed ways, they did speak, sometimes disrupting the very tropes that confined them.

Looking Forward: From Object to Author

Today’s audiences are increasingly aware of the need for more accurate and respectful representation across media. A growing number of Native creatives are reclaiming their stories and reshaping how Native life is portrayed. From the critical success of TV series like Reservation Dogs to the work of Indigenous filmmakers and writers telling their own stories, there is a powerful movement underway to shift Native people from objects of the narrative to its authors.

Museums have a role to play in this transformation. Exhibitions like The Cinematic West offer opportunities to reflect on how artists like Remington & Russell have helped shape and sustain certain images of the West. Through programming like Dr. Black’s lecture and examining the intersections of art, film, and Indigenous experience, we open the door to richer, more honest conversations about the past and its influence on the present.

As Dr. Black reminds us, the issue is not just about visibility. It’s about voice. Native actors in the mid-20th century were highly visible on screen but rarely allowed to speak for themselves. Today, Native artists, historians, and storytellers are reclaiming that voice, and in doing so, redefining what the American West can mean.

For those interested in exploring this topic further, visit the Sid Richardson Museum’s YouTube channel to view Dr. Liza Black’s full lecture.

Further Reading:

Liza Black, Picturing Indians: Native Americans in Film, 1941–1960 (University of Nebraska Press, 2020)

Michelle H. Raheja, Reservation Reelism: Redfacing, Visual Sovereignty, and Representations of Native Americans in Film (University of Nebraska Press, 2010)

Angela Aleiss, Hollywood’s Native Americans: Stories of Identity and Resistance (Praeger, 2022)

Leave A Comment