Our current exhibition, Remington and Russell in Black in White, examines both artists’ careers in illustration at the turn of the 20th century. Many of the artworks featured in the show are painted in grisaille, which is an art term for grayscale. These black and white works specifically functioned as the source for reproduction in books and magazines of Remington and Russell’s day. Both artists were very deliberate in how and why they were making these artworks to help tell the story of the American West as they imagined it.

Let’s first take a closer look at Remington’s illustration career.

Still in his early 20’s and living in the bustling city of New York, Remington scheduled a fortuitous meeting with the fine arts editor at Harper’s magazine in 1885. Little did the artist know he would encounter Henry Harper himself, the director of the publishing house. Remington showed up to the meeting dressed in western gear and presented himself as a westerner (despite having been born and raised in upstate New York). But the act worked, as the director was impressed by Remington’s sketches he made while traveling out west and immediately landed a job as a staff artist for Harper’s.

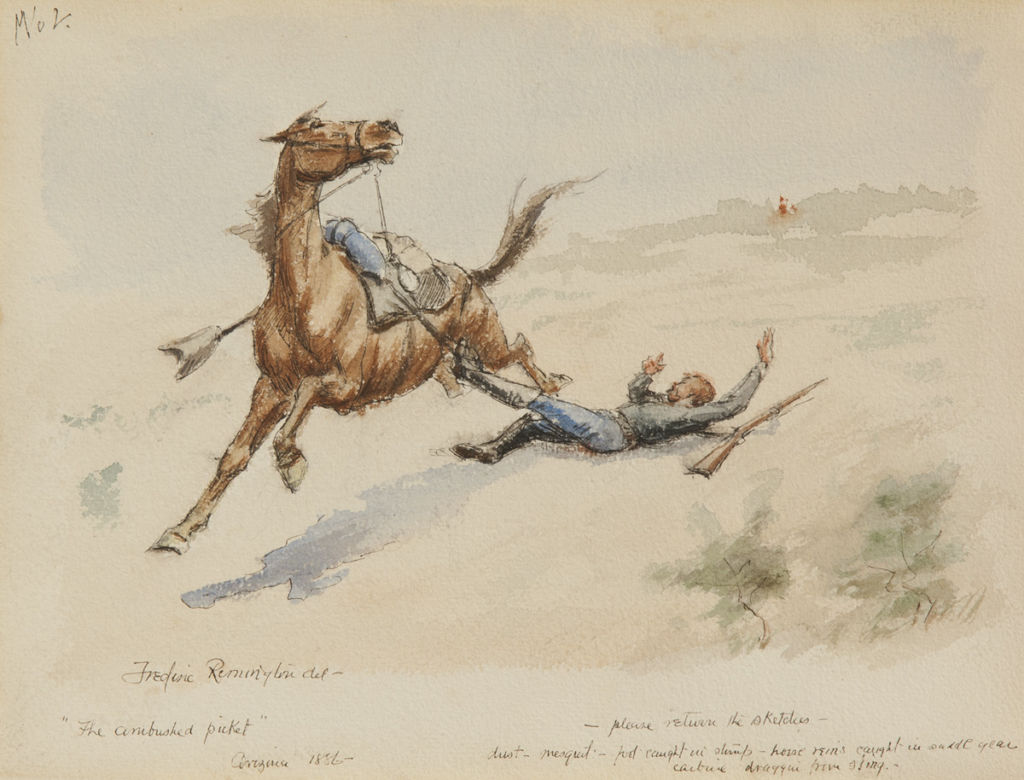

Frederic Remington, The Ambushed Picket, 1886, Pencil, pen & ink, watercolor on paper, 9 x 11 7/8 inches

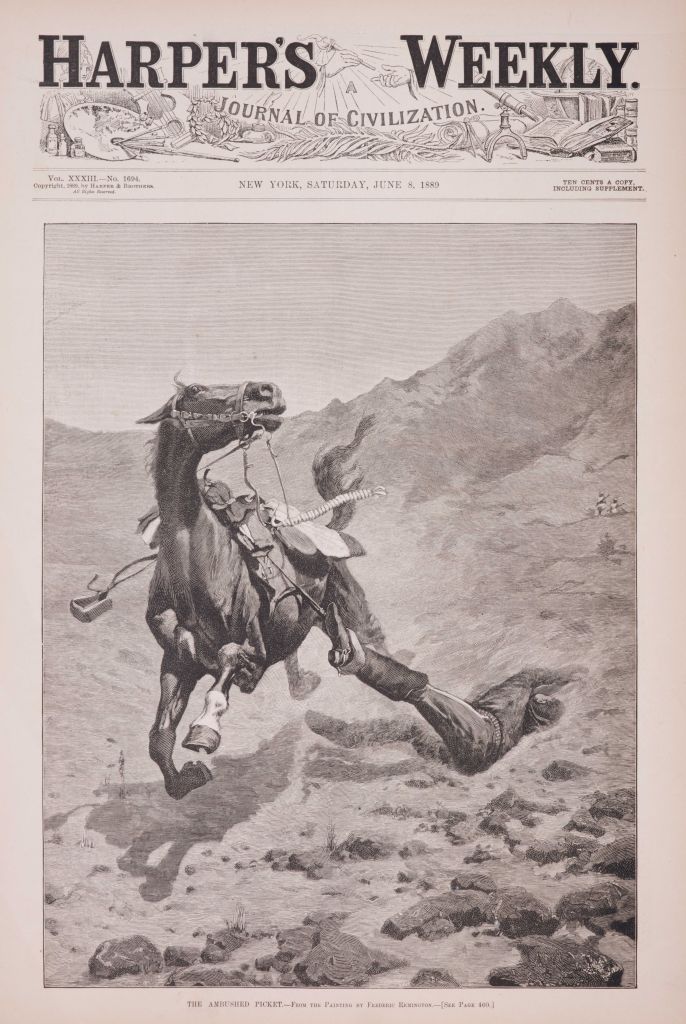

Frederic Remington, The Ambushed Picket, Harper’s Weekly, June 8, 1889, Copyright 1889 by Harper & Brothers

The Ambushed Picket (1886) is one of the earliest works by Remington in the Sid Richardson Museum’s collection. It’s more of a rough sketch, not as fleshed out and finished as his later works. But it was the immediacy of the action and the movement that caught the attention of Harper’s. At the time, Remington’s work wasn’t considered to be good enough to publish as is, so the magazine hired a staff artist to translate and recreate Remington’s images for publication. Notice the difference between the watercolor sketch and the final magazine cover.

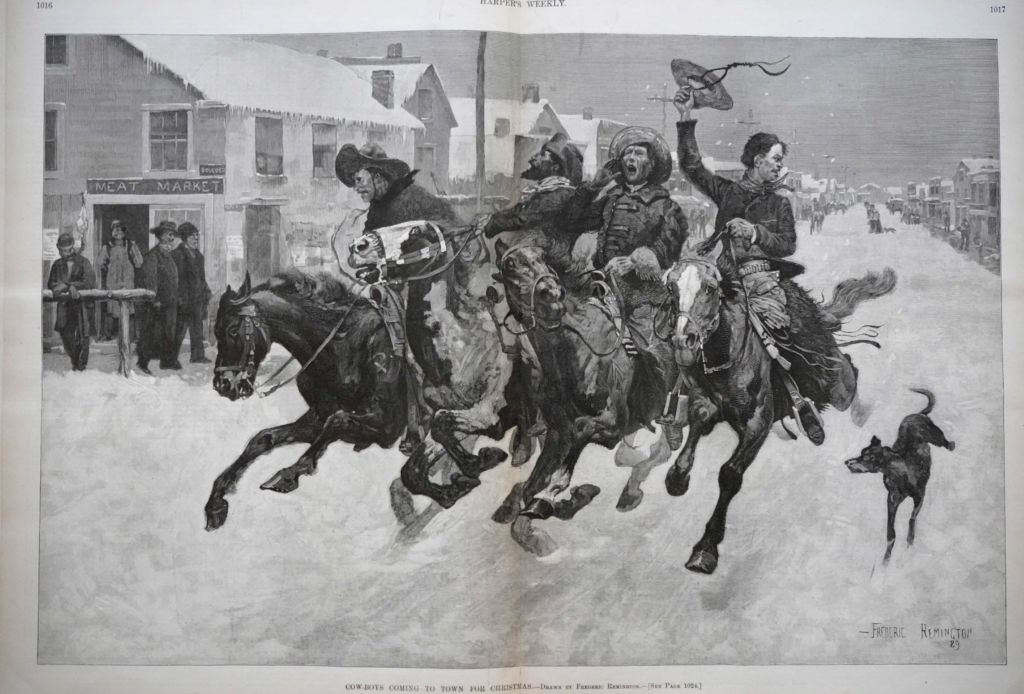

Frederic Remington, Cow-Boys Coming to Town for Christmas, 1889, Wood Block & Magazine Print, Sid Richardson Museum, 2001.1.1.139

Frederic Remington, “Cow-Boys Coming to Town for Christmas,” 1889, Wood Block and Magazine Print, Sid Richardson Museum, 2001.1.1.139

Another work in the exhibit shows the rapid improvement in Remington’s artistic sophistication. Reproduced in 1889, Cow-Boys Coming to Town for Christmas displays Remington adept at figure handling and the naturalism of his horses. After Remington produced the original 26 x 40” oil painting, Harper’s hired artisans to scale down and reverse the image onto a wood block. Multiple artisans divided up the block to expedite the carving process. Once complete, they rejoined the block, retouched any issues, and then the image was ready for printing, producing very clean images. So despite the fact that this was a mass produced illustration, its source was quite handmade!

After Remington started working with Harper’s, he quickly realized he needed to brush up on his painting skills (pun intended!). Thus he enrolled in the Arts Student League, an art school founded in New York in 1875 (and still in operation today). Being in this space brought Remington into the orbit of other artists working in the city, allowing Remington to learn and adapt to what he was seeing. His new circle of artists included Charles Dana Gibson, known for the “Gibson Girl,” elegant cosmopolitan ladies. A close artist friend of Remington’s was Frederick Childe Hassam, who is known as an American Impressionist painter but also produced illustration early in his career.

Frederic Remington, The Puncher, 1895, Oil on canvas, 24 x 20.125 inches

Howard Pyle, “Pirates Used to Do That to Their Captains Now and Then,” 1894, Harper’s Magazine

Another artist Remington knew was Howard Pyle, an illustrator who was known for his pirate subject matter. Included in the Sid Richardson Museum’s collection is the 1895 painting The Puncher, which Remington offered as a trade for Pyle’s painting, “Pirates Used to Do That to Their Captains Now and Then.” Look closely at the lower lefthand corner of The Puncher and one will see where Remington signed “to my Friend H. Pyle.”

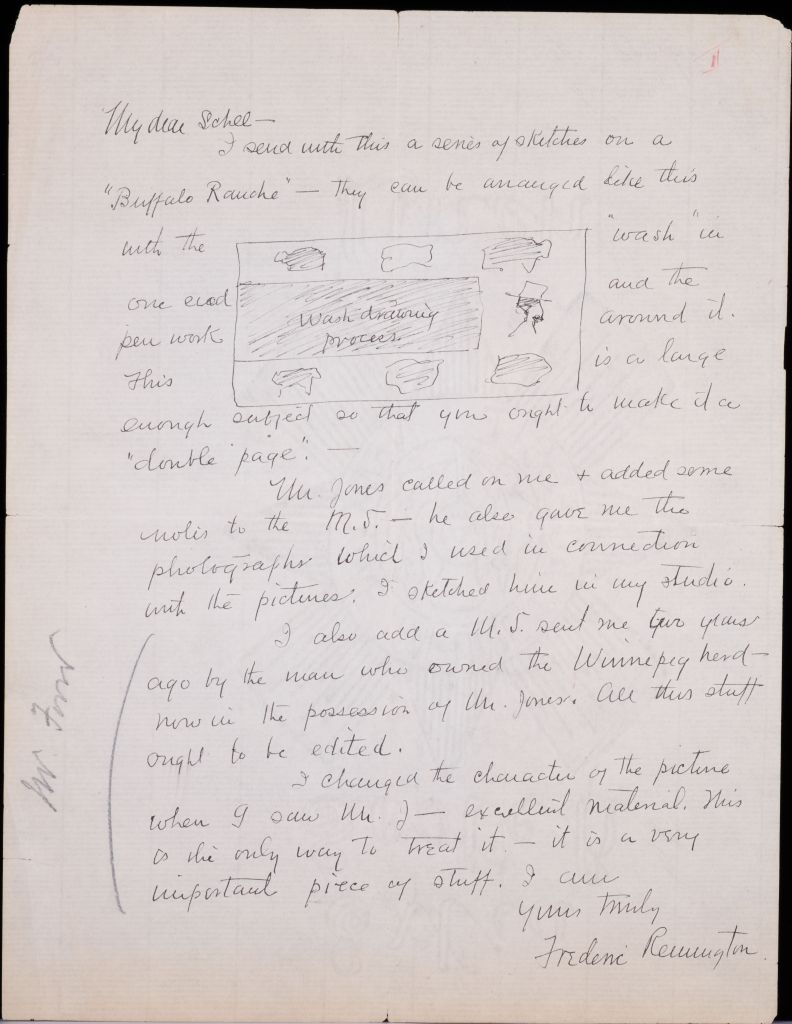

Frederic Remington, Letter from Remington to Fred B. Schell, 1890, Sid Richardson Museum, 1996.2.1.

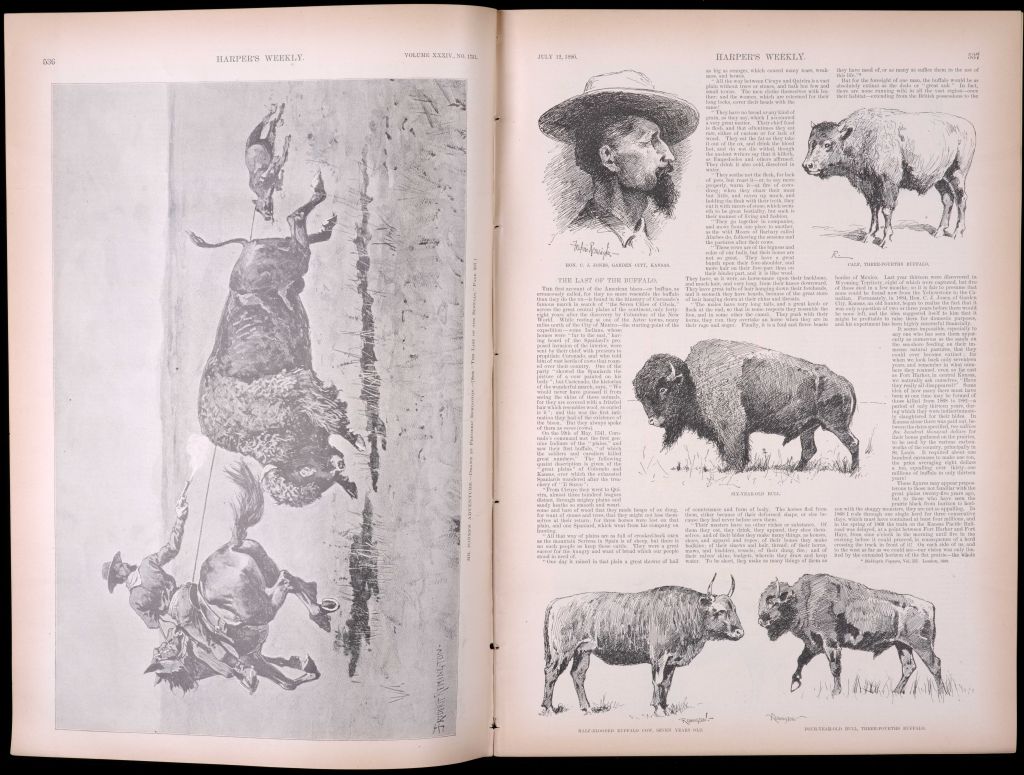

“The Last of the Buffalo” by Henry Inman, Illustrated by Frederic Remington, Harper’s Weekly, July 12, 1890, pp.536-539, Copyright 1890 by Harper & Brothers

The museum’s current exhibition offers a rare glimpse into the working relationship between Remington and his editors at Harper’s Weekly through a letter from Remington. Written in January 1890 to the art director and editor Fred Schell, Remington outlines a double page layout of text and sketches for an article he’s producing. In the letter Remington writes:

My dear Schell,

I send with this a series of sketches on a “Buffalo Ranche”—They can be arranged like this with the “wash” in one end and the pen work around it. This is a large enough subject so that you ought to make it a “double page.”—Mr. Jones called on me & added some notes to the M.S.—he also gave me the photographs which I used in connection with the pictures. I sketched him in my studio.

I also add a M.S. sent me two years ago by the man who owned the Winnipeg herd—now in the possession of Mr. Jones. All this stuff ought to be edited. I changed the character of the picture when I saw Mr. J—excellent material. This is the only way to treat it.—it is a very important piece of stuff. I am yours truly

Frederic Remington

Looking at the final article on display next to the letter, it’s interesting to note the changes in the final layout from Remington’s initial suggestions.

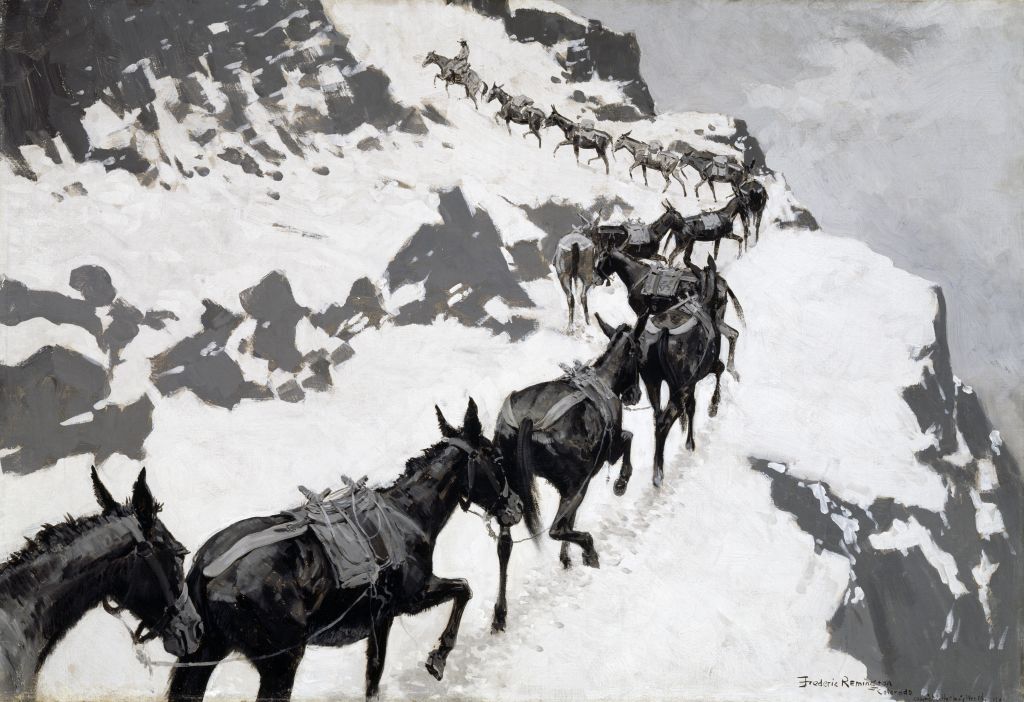

Frederic Remington, The Mule Pack, ca. 1901, oil on canvas, The Hogg Brothers Collection, gift of Miss Ima Hogg, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 43.56

A departure from many of the artworks in this exhibition, Remington’s ca. 1901 oil painting The Mule Pack was an illustration not accompanied by an article. In fact, this was the last painting Remington created for Harper’s Magazine, a contract he maintained for about 15 years. The Mule Pack exhibits aspects of abstract quality. Look at the expansiveness of the white snow across the over geometric areas of gray that read as rocks. This painting shows the beginnings of Remington’s artistic leanings as he’ll continue to loosen up his brushwork and create works inspired by Impressionism. This painting also marks the period when Remington began to dial down his illustration work as he tried to transition his reputation into one of a fine artist.

Let’s now turn to the illustration career of Charles Russell, which looks a little different from Remington.

Russell wasn’t motived to get out and sell his work like Remington was. Rather, Russell just wanted to make art with whatever he can get his hands on. The motivation for Russell to create illustrations came from others who commissioned Russell to make images for their written works.

Charles M. Russell, An Evening with Old Nis-Sú Kai-Yo, ca.1894, Oil, The Petrie Collection

One such example is when John Beacom approached Russell to create 8 illustrations for a book Beacom was writing about a story he heard 1894, “How the Buffalo Lost Its Crown.” On display in our exhibition is an illustration Russell created in which the army officer is listening to a tale told by an old Blackfoot man, Nis-Su Kai-Yo. This is a rare example among Russell’s illustrations as he didn’t paint many oils in black and white. The artist was more adept in watercolor and produced many pen & ink sketches for his illustration work.

After 1903, Charles Russell and his wife/business manager Nancy Russell travelled from Montana to New York City for first time with the purpose of meeting with publishers and establishing contracts for illustration work. Nancy worked on the business end. Meanwhile, Charlie spent time sharing a studio with artist John Marchand from whom Russell would have likely seen some of his black and white illustration works. In the same studio was Will Crawford, another illustrator, usually of political cartoons and reminiscent of Russell’s humor. Another artist in Russell’s circle who enjoyed his own illustration career was his good friend Philip Goodwin (who was a student of Howard Pyle – remember the pirate guy?).

Charles Russell, “Over the Next Ridge, Therefore, We Slipped and Slid, Thanking the God of Luck for Each Ten Feet Gained,” 1905, Watercolor, Private Collection

Charles M. Russell, He Snaked Old Texas Pete Right Out of His Wicky-up, Gun and All, 1905, Watercolor, pencil & gouache on paper, 12 3/8 inches x 17 1/8 inches

The Russell’s trip to New York resulted in a number of commissions (Nancy’s business savvy worked!), including a project for McClure’s Magazine for a story called Arizona Nights by Stewart White. The author recounts tales of life out west on the range, with characters like Texas Pete charging travelers exorbitant prices for water. Russell managed to include so much detail into his compact scenes, a testament to the artist’s ability for storytelling even with such small works. He lets the story unfold across the paintings.

Charles M. Russell, Roping, ca.1925–1926, Gouache on paper, 19 1/4 inches x 15 inches

Made at end of Russell’s career is the latest work in the Sid Richardson Museum’s collection – his ca. 1925-26 work on paper, Roping. This vignette of roping cowboys was probably intended as an illustration for one of the projects the artist had been working on during this period. Russell made work to the very end of his life as his health continued to decline with his final illustrations for his book Trails Plowed Under, published after his death in late 1926.

Both Remington and Russell owe much of their reputation and success to their careers in illustration at the height of the Golden Age of American Illustration. This period of excellence in book and magazine reproduction developed from technological advances that allowed for inexpensive yet high quality images to be reproduced easily and distributed to a wide audience.

Leave A Comment