As millions of settlers moved into the western United States between the 1860s and the early 1900s, they relied on a continent-spanning communications network to connect them to the wider world: the US Post.

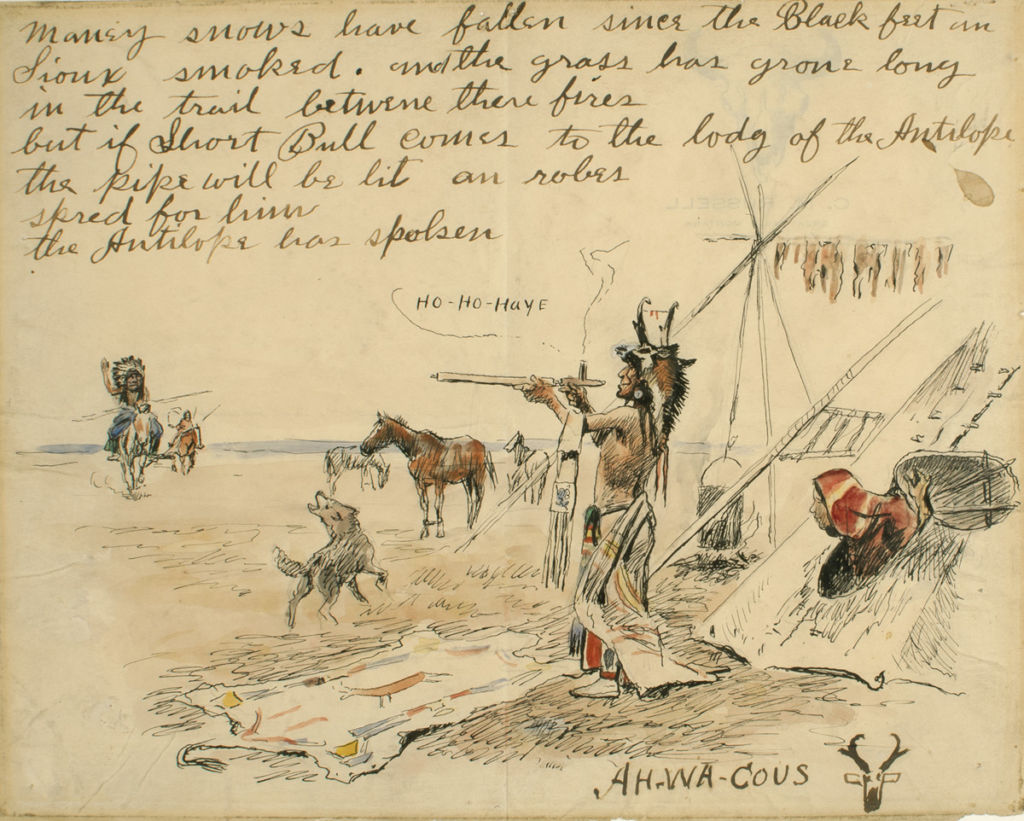

Charles M. Russell, Maney Snows Have Fallen. . .(Letter from Ah-Wa-Cous [Charles Russell] to Short Bull), ca.1909 – 1910, Watercolor, pen & ink on paper, 8 x 10 inches

Thoughts of the American West and the postal service often conjure images of the Pony Express from the mid-19th century. But despite its hold on the American imagination, the Pony Express was a short-lived system, operating for about 18 months run by a private company and delivered little mail in comparison to the larger federal infrastructure of the U.S. Post.

Frank Tenney Johnson, Trouble On The Pony Express, ca. 1910 – 1920, Oil on canvas, 36 1/4 x 28 1/4 inches

Just how remarkable was the U.S. Post? For example, someone living in the late 19th century remote desert of central Arizona could write a letter to a family member in San Diego, California, and traveling over 400 miles over some very rugged terrain, the letter could make it to its destination in four days! The mail allowed one residing in the isolated stretches of the American West to remain connected to a wider world, corresponding with friends and family, as well as subscribing to the daily newspaper and general interest journals.

Salt River Canyon and the Salt River in Gila County, Arizona, 1990. Photo courtesy of Phillip Capper.

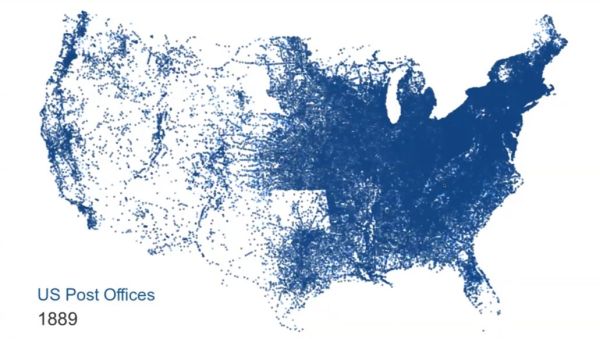

The U.S. Post was the world’s largest communication network in the 1800s. In an 1889 annual report, the postmaster general confirmed that there were about 59,000 post offices in operation around the country, spanning over 400,000 miles of various mail routes. What does that look like?

Scholars like Dr. Cameron Blevins have mapped out the network of the U.S. Post and its development across the country in the late 19th century. And by looking at these visuals, we can assess how this federal infrastructure helped facilitate westward expansion while weaving together the colonization of the American West.

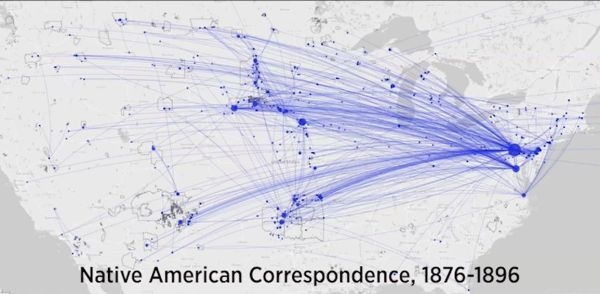

As the federal government forced Native peoples off their land the U.S. Post rapidly established offices in its place. But Indigenous groups were still able to access and use the mail, and did so, in fact, to their advantage.

During this time, the Bureau of Indians Affairs hired special agents to manage the Indian Reservations. Residents of the reservations had to request and obtain permission from these special agents if they wanted to visit other reservations and Native people. Despite the confinement, Indigenous people maintained a life of mobility, both the freedom of geographic movement and the ability to express their ideas widely across boundaries via the U.S. Post.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, Native Americans wrote letters to communicate across reservation boundaries. Massive networks of correspondence tied Native Americans together. Through letter writing, Native people spread ideas that were in opposition to the ideas of the federal government, like religious knowledge such as the Ghost Dance of 1890.

The letters carried news, well wishes, advice about surviving diseases, warnings about smallpox outbreak. By the mid-1880s there is large evidence of intertribal correspondence as a political tool, to collectively discuss and organize protests against U.S. government policies. Of course, the federal agents were not happy with this and tried to suppress Native correspondence. Officials were afraid of the impact these letters would have on the government’s efforts towards assimilation and potentially weaken the reservation system. As a result, Native letter writers became concerned about retribution from their bureau agents as officials began to censor the mail coming and going from the reservations. This forced one group of Lakota at Standing Rock to leave the reservation in the dead of night, cross the Missouri River to mail letters in the nearest white town.

Scholars like Dr. Justin Gage have researched hundreds of letters from Native writers in western reservations that were sent to US officials, presidents, commissioners of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, congressmen as well as newspaper editors and other allies. These letters delineate criticisms of government policies and employees, demanding treaty promises be kept, and the restrictions on their freedoms and cultural expressions. Through use of the US Post, Native Americans forged intertribal bonds while spreading advantageous knowledge and corresponded with white Americans to push for justice and self-determination.

Leave A Comment