*The following is part of a series of blog posts researched and written by Mark Clardy, SRM Docent and independent scholar.*

Listen to the paintings of Charlie Russell, Frederic Remington, and other artists of the West! Listen carefully, and you might hear dusty cowboys serenading restless cattle, or maybe a harmonica just over the horizon. Brush strokes pulse with the beat of Native American drums. Staccato clouds gallop across the sunset, echoing the ochre trills of a distant flute. Bugle calls and saloon pianos, pow-wow dances and tribal medicine songs, even las canciones de la frontera – they’re all clamoring to be heard again.

These frontier sounds and melodies burst onto the cultural stage after the Civil War like a stampede, searing their brands into the hides of our American musical forms: Bluegrass and Hillbilly, Tin Pan Alley, Ragtime, Blues, Jazz, Big Band, and even Classical. Listen carefully, and the paintings will sing for you. It’s the Soundtrack of the American West.

Think of this blog series as a musical rodeo, a corral (chorale?) filled with the symphonies of distinctly American sounds. The opening gate of the corral is the year 1861 – the year Frederic Remington was born. On the other side is 1926 – the year Charlie Russell died. Between the corral gates is our arena, an expanse of hour-glass sand spanning 65 years, the period of time in which many artists of the American West worked. This is the music that our artists heard, the songs that they painted. Such was the musical milieu in which the art of the American West was created.

So check your spurs and saddle up. We’re headed for a Wild West musical extravaganza!

Series Concept and Scope

This continuing blog series will harmonize Western art and music by matching the art of the Sid Richardson Museum with music of the American West, 1861-1926. Each topic in the series will be presented as a separate “Symphony”, beginning appropriately with an “Overture” to introduce key historical and cultural themes, which influence the music that we’ll hear in later blogs or “Movements.” Each Movement will feature at least one painting at The Sid and music that relates in some way to the painting. As currently envisioned, forthcoming Symphonies will include: music of Native America (introduced below), songs of the cowboys, songs that the artists knew, and “canciones de la frontera” (songs of the border).

Acknowledgements

All music and illustrations are from materials in my personal collection, except as noted in the text. The music in this series is out of copyright; my transcriptions are available by hyperlink to the “Community” or “Public Scores” section of Noteflight.com, a website for composers and arrangers.

I want to thank several people for helping with this project. Timothy D. Watkins, Associate Professor of Musicology at the TCU School of Music, Ft. Worth, Texas, provided helpful comments on an early draft of this blog, and also clarified the development of ethnomusicology as an academic discipline. Judith Gray, Folklife Specialist at the American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, Washington, D. C., also provided helpful comments and guidance on Native American music. And finally, I want to thank Leslie Thompson, Director of Adult Programs at the Sid Richardson Museum, who has enthusiastically guided this expedition into the music of the Sid Richardson Museum collection of Western art. As per tradition, any errors, omissions, opinions, or even outright (but completely inadvertent!) falsehoods are my own responsibility, and can be addressed in the comments section.

And now…

On with our Wild West Musical Extravaganza!

Music of Native America

In this “Symphony of Native America” we’ll hear some of the earliest recorded music of American Indians, and renditions of their songs as transcribed by early missionaries, anthropologists and other researchers. We’ll hear music based on “authentic Indian melodies,” and music which incorporated Native American lyrics. We’ll also hear some popular American parlor songs which musically signaled “Indian-ness” in various ways, and others that conveyed common attitudes about American Indians.

Overture to the Music of Native America

Several key concepts from that time period were rooted in literature, science, and history, all of which influenced composers’ reactions to Native American Music. Many of the ideas that shaped responses to indigenous music have been proven wrong over time, and are seen today through the lens of Anglo colonizers. Some of the ideas that influenced music were “The Vanishing Race,” “The Noble Red Man,” and the appropriation of indigenous culture through the concept of “primitive music”. This idea was also bound with notions of finding in indigenous music a truly American sound.

“The Vanishing Race”

Blue Juniata, 1844

The “Vanishing Red Man,” destined for oblivion, is an idea woven tightly into the history and mythology of the American West, first popularized by James Fenimore Cooper in his 1826 novel, The Last of the Mohicans; even the title expresses the idea. Four years after publication, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, leading directly to the Trail of Tears in which thousands of indigenous people were forced to leave their homes and travel West beyond the Mississippi. For those indigenous people who were not killed in the process, the American government confined them to reservations. As a result of military conflicts, invasion, and forced migration, many tribal populations declined, leading many Americans to believe that the American Indian was “vanishing,” and several popular songs of the mid 1800s touched on this misguided concept of the disappearance of the American Indian.

Mrs. Marion Dix Sullivan became the first woman to write a hit song in America when she wrote “The Blue Juniata” in 1844, about “an Indian girl, the Bright Alfarata” and her warrior lover, set on the Juniata River in Pennsylvania. The last verse laments Alfarata and her lover, long gone, but “Still sweeps the river on, The Blue Juniata.”

The Dark Eye Has Left Us, 1848

The Indian’s Prayer, 1846

“The Indian’s Prayer” (1846) is a longing plea of a homesick, displaced American Indian wanting to return to his home which is identified as being not in the east, but “in the far distant west”.

An early song that made use of actual Native American sources was “The Dark Eye Has Left Us” by William R. Dempster (1848). The lyrics by John Greenleaf Whittier (1843) feature an unusual recurring line in the Algonquian Pennacook language of New Hampshire: “Mat wonck kunna monee.” The sentence is translated as: “We see [or hear] her no more,” and serves as a lament for the women of the Pennacook tribe who have died, and are seen no more.

Even eighty years after its publication, The Last of the Mohicans was still an influential novel when Joseph Kaiser wrote “Uncas: The Last of the Mohicans” in 1904. This Ragtime March and Two-Step piece is a “characteristic,” i.e., a piece which is supposedly ‘characteristic’ of Native Americans. Ragtime was very popular at the turn of the century, but it is, however, a decidedly un-Indian style.

Uncas: The Last of the Mohicans, 1904

Noble vs. Savage

The second theme in our Overture is “The Noble Red Man,” also introduced in The Last of the Mohicans. The two themes work together: whether an American Indian was considered “noble” or “savage” depended on his willingness to paddle his canoe quietly into oblivion’s sunset. Again, these terms were applied through the lens of Anglo colonizers on a group of people deemed “other” or non-Western. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow revisited both themes thirty years later in his epic poem The Song of Hiawatha (1855), a story of the heroically tragic, soon-to-vanish American Indian hero. In the story, Hiawatha, the son of Wenona and the West Wind, meets mythic challenges, marries Minnehaha, and then glides in his birch bark canoe into the fabled sunset after her death. These two blockbusters, Mohicans and Hiawatha, more than any other literary works, created the popular image of the American Indian, and had a lasting impact on the portrayal of Native Americans in American music and culture. Cooper introduced the imagery, but Longfellow hammered it tightly into the American consciousness with percussively pounding, repeating syllables. You may recognize the most famous (and often parodied) lines from the birth of Hiawatha (Canto III, line 64) and his departure (Canto XXII, line 1): “By the shore of Gitchee Gumee, By the shining Big-Sea-Water…”

Hiwatha, 1891, Remington Illustration Edition

“Minnehaha, or Laughing-Water Polka” by Francis H. Brown (1856)

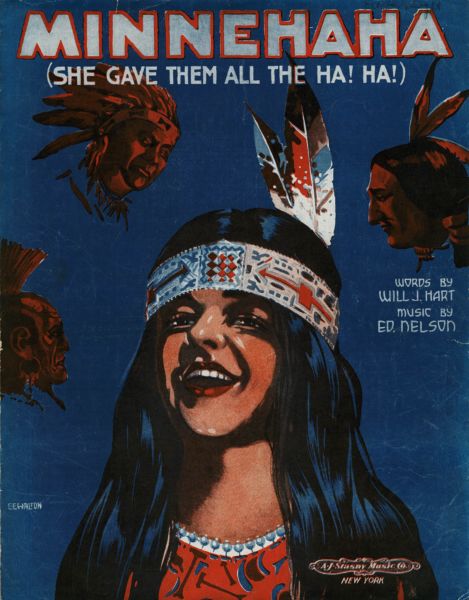

The only similarity between Hiawatha, the historic cofounder of the Iroquois Confederacy, and Longfellow’s Hiawatha, is the name. In spite of that little detail, Longfellow’s imagined account of Hiawatha blossomed into a wildly popular American craze, and was published in multiple editions; the 1891 edition was illustrated by Frederic Remington. Longfellow’s depiction of Native American culture, widely assumed to be accurate – for all American Indians – inspired a century-long national avalanche of Hiawatha and Minnehaha themed songs, pageants, plays, operettas, and recitals, from serious to comedic to burlesque. Some examples of Hiawatha-themed songs are “Minnehaha, or Laughing-Water Polka” by Francis H. Brown (1856), “Hiawatha: His Song To Minnehaha” by Neil Moret and James O’Dea (1903), “Minnehaha – She Gave Them All the Ha! Ha!” by Ed Nelson and Will J. Hart (1918), and “Hiawatha’s Melody of Love” by George W. Meyer (lyrics by Alfred Bryan & Artie Mehlinger, 1920). Hiawatha mania continued to flourish in cartoons, comic books, and television sit-coms, until western movies and television shows became popular in the 1950s – also, with little connection to the realities of Native America.

“Hiawatha: His Song To Minnehaha” by Neil Moret and James O’Dea (1903)

“Minnehaha – She Gave Them All the Ha! Ha!” by Ed Nelson and Will J. Hart (1918)

and “Hiawatha’s Melody of Love” by George W. Meyer (lyrics by Alfred Bryan & Artie Mehlinger, 1920)

Just “Follow The Science”

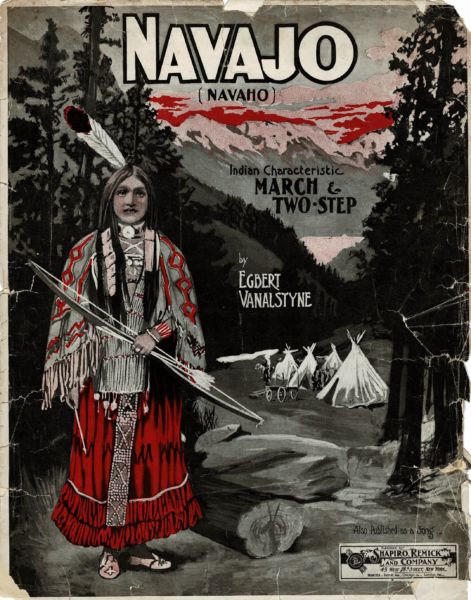

Navajo, 1903

A few years after The Song of Hiawatha hit the bookstores, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Guided by “The Science,” Social Darwinism decreed that civilization’s ever-advancing light of progress would conquer the savage darkness and superstition of lesser races. “The survival of the fittest” explained why the extinction of Native Americans was inevitable. Seen not as an attitude, but as an immutable force of Nature, this theme plays repeatedly throughout the Soundtrack about Native America, driven by the shallow command to “follow The Science!” (always capitalized, never questioned).

The Sun Dance, 1901

The pervasive racism of the Progressive era also appeared in the popular music of the time. For instance, “Navajo” was the first success for New York song writers Egbert Van Alstyne and Harry Williams, and was performed in the long-running 1903 Broadway production of “Nancy Brown.” It is a ‘comical’ story about a Navajo woman and her Black lover. In the popular music about Native Americans, there were several interracial love songs which almost always featured an “Indian maiden,” never an American Indian man.

It should not be surprising that various musical conventions became stereotypical signals for “Indian,” regardless of tribe. One of the most common motifs was a persistent repetition of four bass clef drum beats: “DUM, dum, dum, dum; DUM, dum, dum, dum…” Listen for these drum beats in “The Sun Dance”, a piano piece by Leo Friedman (1901), and try to identify other “Indian sounding” phrases. As we progress through this series, we can compare these motifs with actual Native American music.

The Latest in Recording Technology

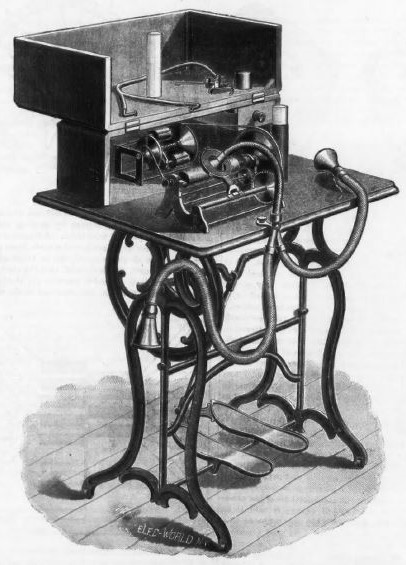

Illus: Graphophone, July 14, 1888 Electrical World

vol 12, no 2, p 16, Fig 4 (via Internet Archive)

The theme of inevitable demise for all things “primitive” also sprouted like a weed in the garden of musical concepts. The trendy evolutionary view was that the music of Native Americans was equivalent to the primordial stages of Western classical music, and since theirs was believed to be a rapidly vanishing culture, it was a race against time to record and study their music before it disappeared entirely. But it was a laborious process, to have a patient American Indian singer repeat a song over and over, while transcribing it on paper. Then in 1877, Thomas Edison invented the graphophone (later called the “phonograph”) which unleashed a wave of technological developments with vast implications for the music industry and the scientific study of music.

The invention worked by funneling sound down a cone to a needle which vibrated with the sound and cut a jagged-edged line into the rigid waxy coating on a rotating horizontal cylinder. The needle was moved slowly across the cylinder as it rotated, creating a continuous groove in which the sound waves were physically recorded. Playback was the reverse process: as the needle ran along the groove of the rotating cylinder, the jagged edges created vibrations in the needle which were then picked up and amplified in the cone. Wax cylinders were later replaced by flat discs with a spiral groove. Here is an example of an Omaha song wax cylinder recording from about 1895, from the Library of Congress.

Preserving the Musical Primordium

Activity in musical anthropology exploded as researchers fanned out across North America, and the world, armed with the new recording device. They could then play their recordings back in the lab to transcribe what they heard (or what they thought they heard) into standard musical notation. But this process had a few inherent problems.

Using Western musical notation to transcribe non-Western music is a feat somewhat akin to using a flat-head screwdriver to turn a Phillips-head screw; it can get the job done, but not very well. Non-Western music cannot be expected to conform to Western standards such as Western scales with precise pitch intervals and A=440. Think of the notes hit by some ‘singers’ who sound slightly “off-key” – either “flat” or “sharp.” Normal musical notation could not convey these microtones, or the pitch of sounds that were not-quite-in-key to “Western ears.” But common musical notation was the only tool they had.

A second complicating factor was calibration of the recording equipment. Without recording a known tuning fork pitch before each recording session, there was no way to determine later what the recorded pitch actually was. In spite of these limitations, the recordings are a valuable link to our musical past, and many are now available digitally at the Library of Congress; several were also transcribed and published.

The anthropologists and ethnologists who conducted this musical research played a foundational role in the later development of the field of ethnomusicology in the mid-twentieth century. Among the most prominent of them were: Alice Cunningham Fletcher, Frances Densmore, and Natalie Curtis. There were also several men who were recording tribal music around the turn of the century, but these women were the most influential researchers.

Seeking an American Sound: The Indianist Movement

By the turn of the century, even the “high-brow” American culture began to rebel against its European parentage. Encouraged by Antonín Dvořák in 1893, many American composers began to look to the music of Native Americans for inspiration. With no concerns for cultural misappropriation, composers in the “Indianist Movement” strove to create a uniquely American (i.e., non-European) sound using either the published transcriptions of American Indian music, or source materials from their own interactions with Native Americans. Indianist composers preserved the original Native American melodies in their works to varying degrees. Some left the melodies intact, while others significantly altered both melody and rhythm, submerging them under harmonic layers. The Indianists were active up to about 1930; some of the leading ones were: Charles Wakefield Cadman, Arthur Farwell, Carlos Troyer, Thurlow Weed Lieurance, and Amy Beach.

The Overture Takes Shape

These swirling cultural themes and scientific advances form the root chords for our overture: 1) the noble, suffering Native American; 2) his anthropologically priceless music which must be preserved and studied as a “primitive” stage of our own; 3) the urgent need to do so because of his supposed imminent and evolutionarily decreed demise; and 4) above all else, the cultural imperative to borrow his melodies for a distinctly American style of music. This whirlwind of influences played out in the late 1800s as a complex fugue with frequent unresolved dissonances that collided with the popular emerging sounds of ragtime, blues, and jazz, in a gloriously cacophonous “Soundtrack of the West.”

In future posts, we will venture into our arena with the artists of the West for several different Movements in our Symphony of Native America. This introductory blog closes with a short Movement based on Buffalo Runner – Big Horn Basin by Frederic Remington and the music of the Métis people.

Buffalo Runners – Big Horn Basin, Frederic Remington

Buffalo Runners—Big Horn Basin | Frederic Remington | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 30.125 x 51.125 inches

THE MÉTIS BUFFALO HUNTERS

Red River – Ball at Pembina, 1860, Harpers New Monthly Magazine, v21, n125, page 585

Red River – Buffalo Chase, 1860, Harpers New Monthly Magazine, v21 n125, pg 581

Frederic Remington painted Buffalo Runners – Big Horn Basin in 1909. This impressionistic painting depicts several Métis hunters, identified by their wind-whipped sashes. These descendants of Canadian French and Scottish traders and their Native American wives (Cree, Ojibway, Algonquin, etc.) were often treated as outcasts, neither Indian nor European, but “mixed.” Settling in Canada, primarily in the Red River valley of Manitoba, and in the U. S. in Montana and other northern tier states, they developed their own language, Michif, which is an unusual mix of Canadian French noun phrase constructions and Cree verbal syntax. Their music also combines features from their Native American heritage with French and Gaelic songs and instruments, particularly the fiddle.

The “Red River Jig” is thought of as the “national anthem” of the Métis people, with dance steps from the First Nation pow-wow of Canada, and the fiddle music from their European ancestry. There are many versions of the tune which has its origins in the Québécois tune, “La Grande Gigue Simple.”

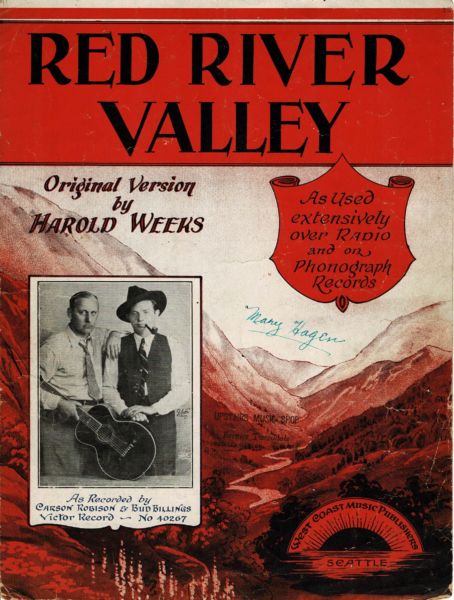

In Texas, the song “The Red River Valley” is generally assumed to be a cowboy song that refers to the border river between Texas and Oklahoma. However, the song most likely refers to the other Red River, flowing northward from the border between Minnesota and North Dakota to the Hudson Bay. It probably dates from the 1870 Red River Rebellion, between the Métis and Canadian government, and was widely known across the northern prairies in the 1890s. Canadian folklorist Edith Fowke claims that the song is a Métis girl’s lament over the departure of her Anglo lover, a soldier who came west to suppress the Red River Rebellion (Edith Fowke, “The Red River Valley Re-examined,” Western Folklore Volume 23, Number 3, pp. 163-171, July 1964.) After all, a Texas cowboy might bid his darlin’ “Adios!”, but never “Adieu.”

Red River Valley, 1929

Leave A Comment