This year our lecture programs have taken us around the world, from exploring the influence of Buffalo Bill on the youth of 1950s Belgian Congo, to the global influences on the development of Western Horse cultures. We continue that journey with a trip across the Atlantic by exploring the reciprocal dialogues between French and US culture through interests in the American West with Dr. Emily Burns’ talk titled Mobile Arts, Fluid Ideas: The American West in France / France in the West.

Interest in and representations of the American West was not exclusive to American artists like Charles Russell and Frederic Remington. Ideas about the West circulated through texts, images and objects traveling for exhibition in Europe, as well as with the artists who went overseas for artistic training and inspiration. This movement of ideas allowed conceptions of and receptions of the American West to flow fluidly between the United States and France between the 1860s through 1910 and beyond.

Universal Exposition, 1867, Paris, France, Public Domain

For example, during the International Exposition of 1867 in Paris, Hudson River School painter Albert Bierstadt exhibited two works of grand scale representing the American West. His 1863 painting The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak depicts at the forefront of the composition a band of Shoshone people against the backdrop of the Wind River Range of the Rockies in present-day Wyoming. In addition to its popular reception, the painting won a prize at the Exposition, and was later acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 1907.

Albert Bierstadt, The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak, 1863, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, Public Domain

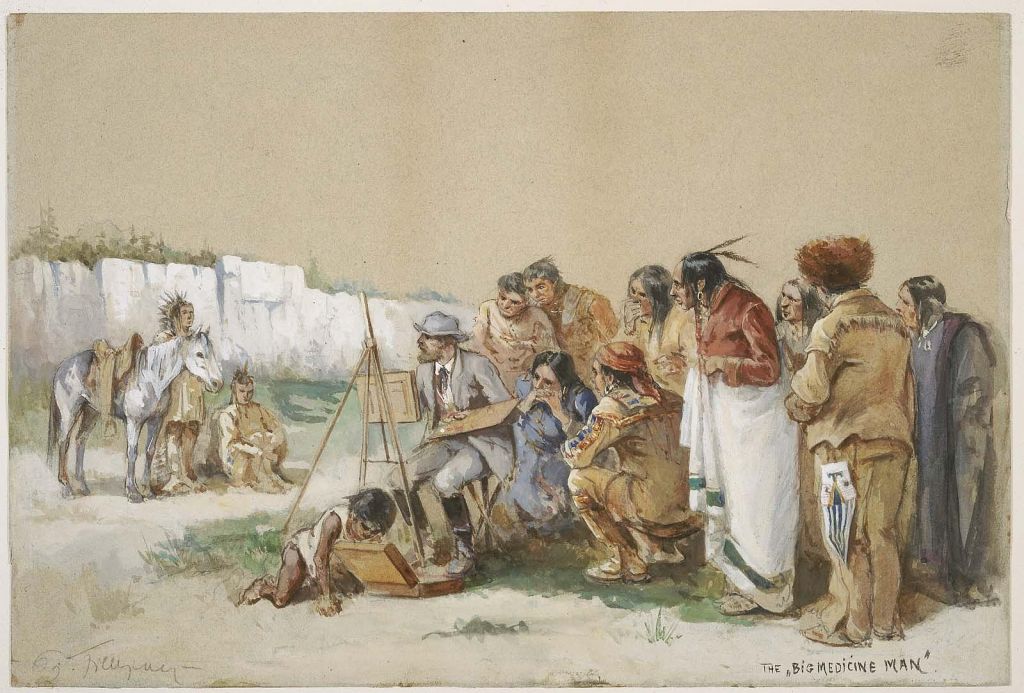

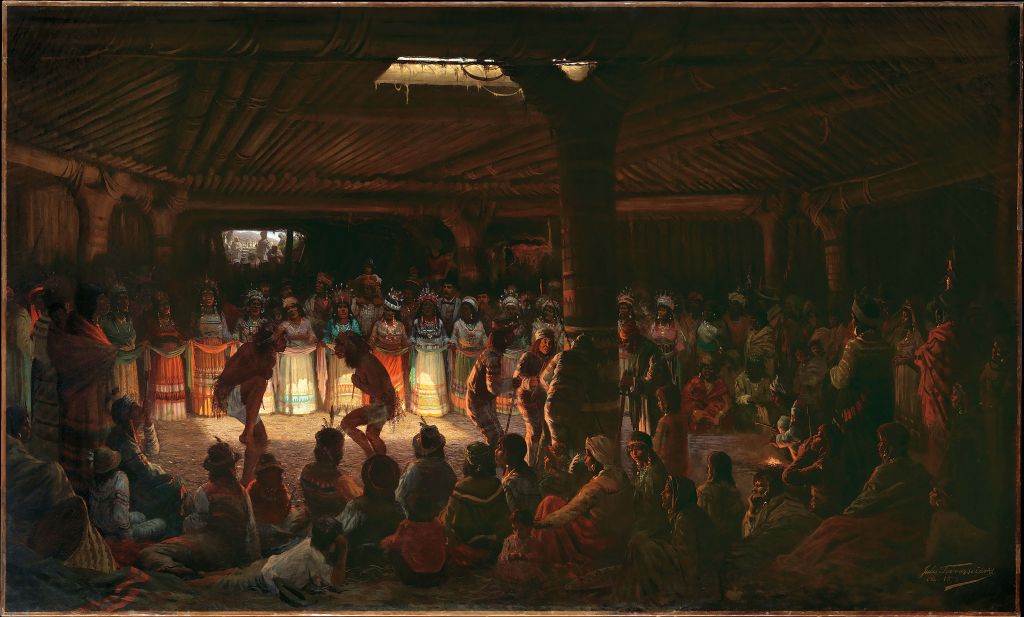

The American West as both a concept and an actual place was considered by some French artists as forward looking and something new to discover. In the 1870s, French artists like Paul Frenzeny and Jules Tavernier travelled to the American West while working on commission for Harper’s Weekly and Century Magazine. Artworks like Frenzeny’s The “Big Medicine Man” and Tavernier’s Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California, show the artists’ interest in depicting American Indian communities. Both Frenzeny and Tavernier went on to have successful illustration careers in the American West, and cultivated both American and French patrons for their work.

Paul Frenzeny, The “Big Medicine Man,” 1873-87, Transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite pencil on blue-gray paper, 57.256, Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Watercolors and Drawings, 1800–1875, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Jules Tavernier, Dance in a Subterranean Roundhouse at Clear Lake, California, 1878, 2016.135 Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2016, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, Public Domain

When the Universal Exposition returned to Paris in 1889, depictions of the American West were well-represented in the American Hall. Simultaneously, during the world’s fair, William F. Cody’s very popular wild west show offered performances in Paris twice a day over a span of 7 months. One of the most successful and best-known French artists who engaged with the American West through Buffalo Bill was Rosa Bonheur. Bonheur made about 50 artworks as a result of her encounters with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, including a portrait of Buffalo Bill himself. The American West was a source of great inspiration for Bonheur who had “always been anxious to see the broad prairies, its high mountains, and the free life of the west.”

Rosa Bonheur, Buffalo Bill Cody, 1889, oil on canvas, Whitney Gallery of Western Art Collection, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Given in memory of William R. Coe and Mai Rogers Coe, Public Domain

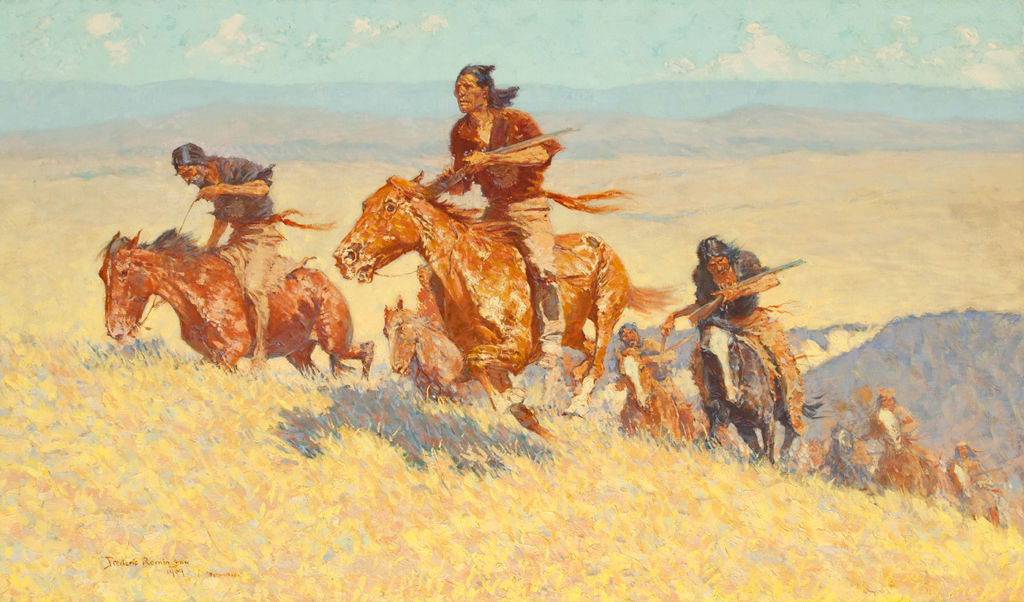

Just as the French were exposed to artists of the American West, American artists like Frederic Remington were influenced by the French through the aesthetic of Impressionism. Having lived and worked in New York City for much of his career, Remington would have seen the first official showing of French Impressionist artworks on US soil in 1886 (where now-famous paintings like George Seurat’s Island of La Grand Jatte were on display).[1] And by the 1890s, Remington became friendly with many of the American Impressionists who were part of the group known as The Ten, including his friend, Childe Hassam. As Remington became more established in his career, towards what becomes the last decade of his life, the artist began to adapt the light-filled palettes, purple shadows, and loose brushwork of the impressionist aesthetic. These aesthetic choices are on full display in the Sid Richardson Museum’s 1909 Buffalo Runners – Big Horn Basin.

Buffalo Runners—Big Horn Basin | Frederic Remington | 1909 | Oil on canvas | 30.125 x 51.125 inches

But here we have merely scratched the surface of this transnational discourse between the US and France through visual and material culture as well as performance. To learn more about how the American West became part of the French imagination in the 19th century, watch Dr. Emily Burns’ talk or check out her book, Transnational Frontiers: The American West in France.

[1] Works In Oil And Pastel By The Impressionists, 1886 by American Art Association, page 23, https://archive.org/details/WorksInOilAndPastelByTheImpressionists1886RCA.AmeMisc1886a/page/n21/mode/2up

Leave A Comment