Violent Motion: Frederic Remington’s Artistry in Bronze

November 8, 2012 – August 11, 2013

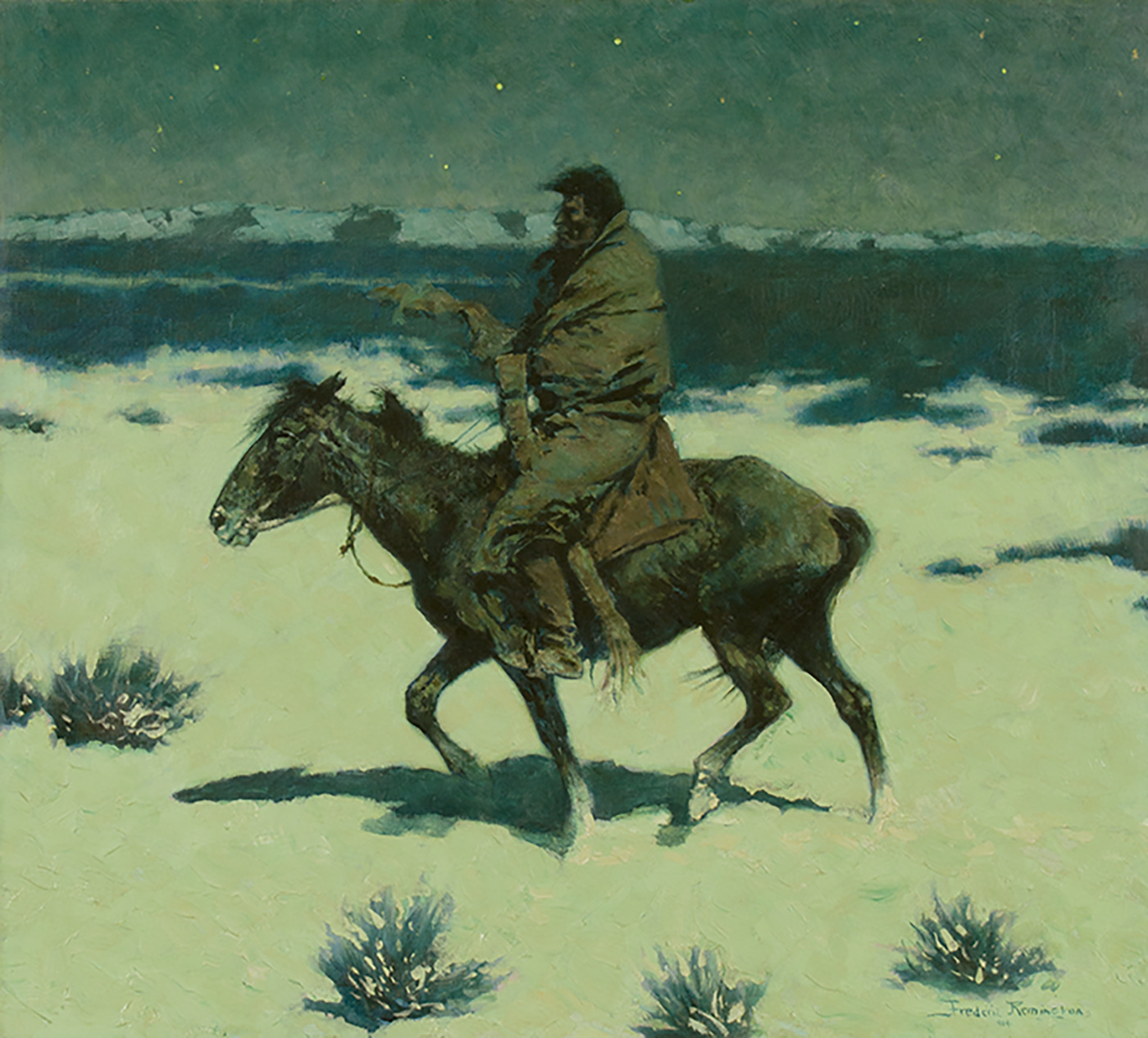

As Sid W. Richardson once observed, “Anybody can paint a horse on four legs, but it takes a real eye to paint them in violent motion. All parts of the horse must be in proper position, and Remington and Russell are the fellows who can do it.” Although both of these great Western artists were skilled at painting horses and men in vigorous action, they also excelled at conveying the same aspects in sculpture. Frederic Remington, in particular, succeeded in creating some of the finest and most memorable action-filled bronzes of any American sculptor of his time.

To mark the thirtieth anniversary of the Sid Richardson Museum, this special exhibition examined the relationship between Remington’s vivid depictions of “violent motion” in his two-dimensional paintings and his three-dimensional sculpture. Remington was already a well-established painter when he decided to attempt sculpture, with no formal artistic training in that medium. His subsequent success was due in part to his ability to recognize that, while painting and sculpture shared similarities in subject matter, composition, movement, and form, they nevertheless had to be envisioned in fundamentally different ways. Remington often observed that it took him some time to adjust his artistic eye when moving from one medium to the other. In the end, he was one of very few American artists to have mastered both mediums.

This exhibition also celebrates the deep friendship that existed between Sid W. Richardson (1891–1959) and Amon G. Carter (1879–1955). The two men shared an abiding love for the art of the American West, and their legacies have enriched the lives of many people. The Museum was grateful to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art and anonymous collectors for the loan of key works for this exhibition.

Rick Stewart Ph.D., Guest Curator

Two Methods of Casting

Remington’s bronzes were produced by two principal New York foundries: the Henry-Bonnard Bronze Company that cast the artist’s work from 1895 to 1898; and Roman Bronze Works, which took over the casting activity in 1900 and worked closely with Remington until his death in December 1909. The Henry-Bonnard Company specialized in the sand casting method, which comprised three basic steps to produce a bronze: preparing a negative mold from a plaster cast of Remington’s original model, casting the bronze, and cleaning and coloring the cast. The sand casting process utilized a sand mold which made a firm negative impression of the plaster model. The inflexible nature of the mold and its inability to conform to complex contours usually required that large or irregularly shaped models be cast in a number of separate pieces before being reassembled. Remington’s The Broncho Buster, for example, was cast in approximately twenty pieces. With the sand casting process, Remington had no opportunities to make any changes to the model before it was cast into bronze.

The Roman Bronze Works foundry specialized in a revival of the lost-wax process, which had many advantages over the sand casting method. Complex models such as Remington’s, having numerous contours, undercuts, and highly textured surfaces, could be cast in fewer pieces due to the greater flexibility of the wax intermediary model. With this process, Remington’s The Broncho Buster needed to be cast in only two pieces — the base and the upper part consisting of the horse and rider. Because the molds could be reused, additional castings were also possible. Most importantly, this process allowed Remington opportunities to rework the wax model prior to casting; he therefore was able to have much greater control over the final appearance of the bronze. Remington was elated by this aspect, and he became much more directly involved in the casting process. The result was some of the most innovative and finely-wrought bronzes in the history of American sculpture.