THE CINEMATIC WEST: The Art That Made The Movies

May 3rd, 2025 – April 20, 2026

May 3rd, 2025 – April 20, 2026

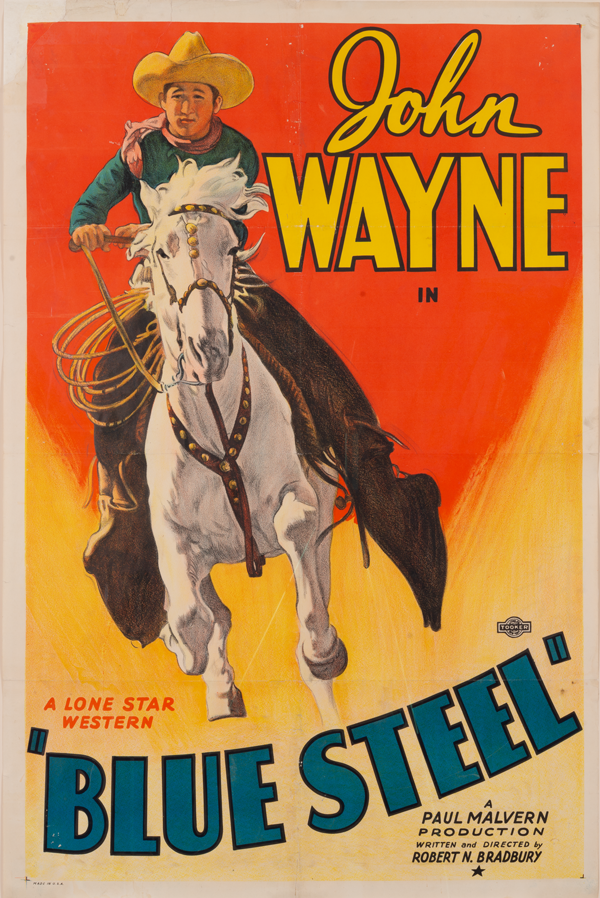

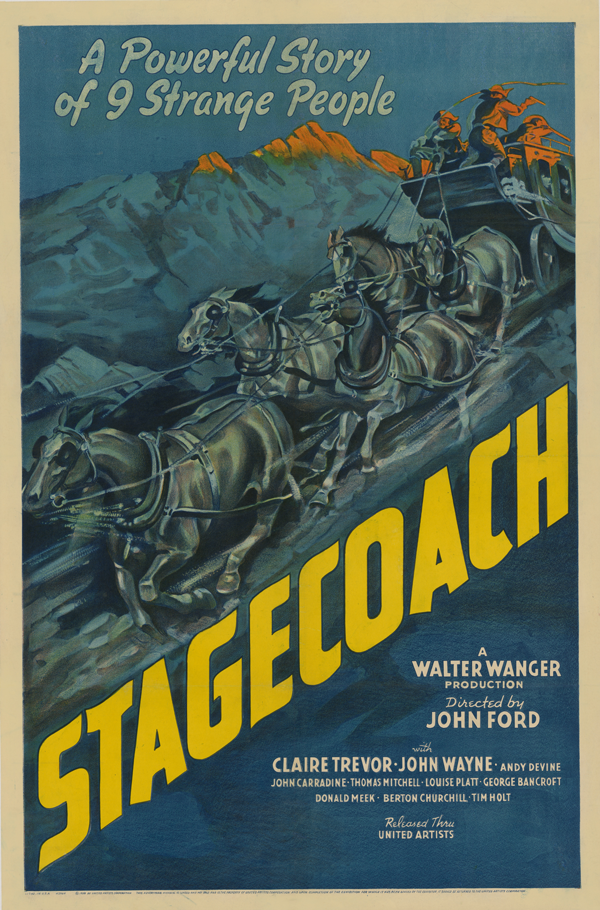

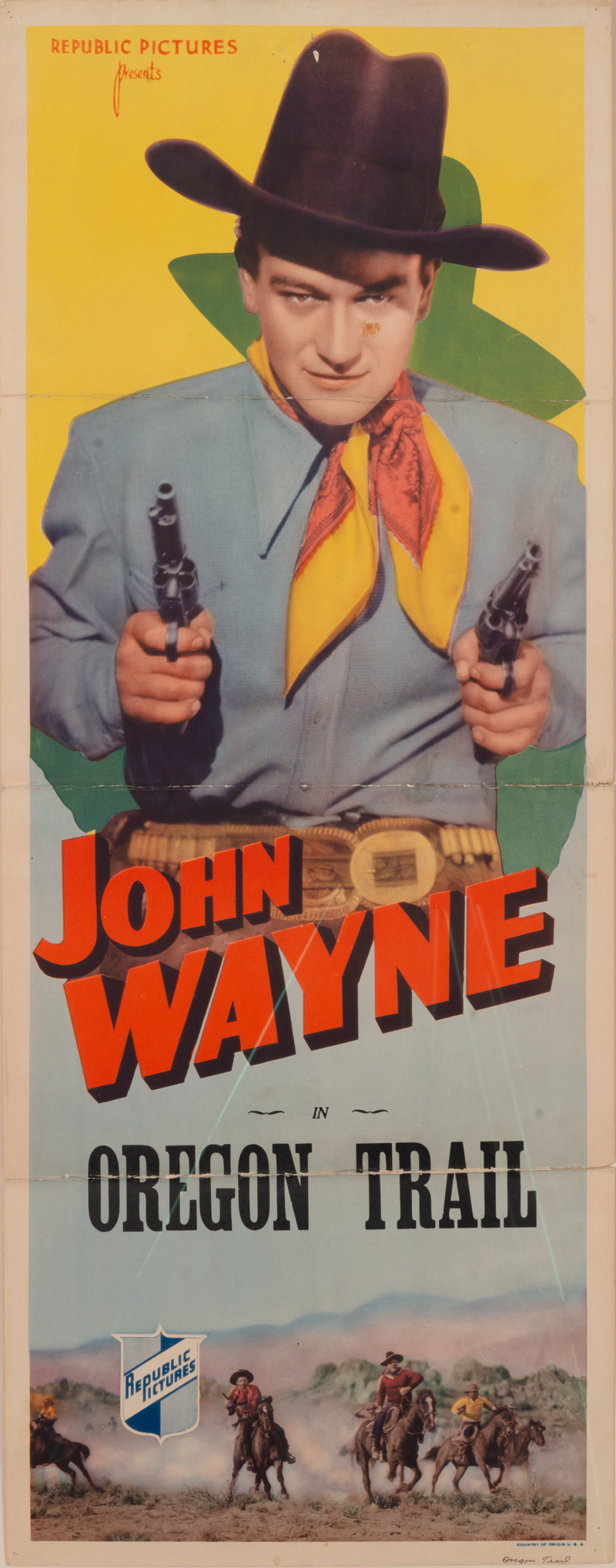

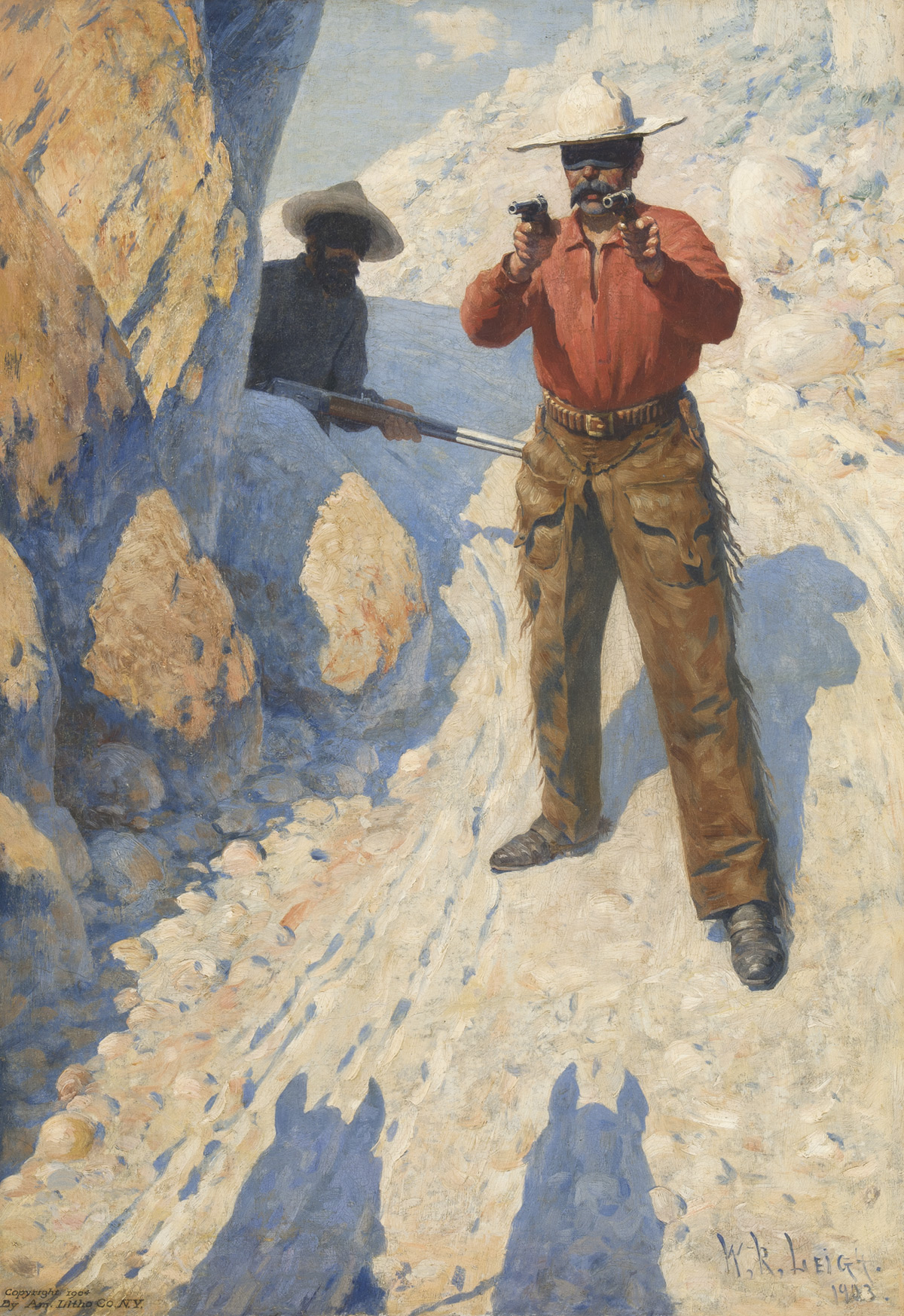

The Cinematic West: The Art That Made The Movies examines the connection between artists Frederic Remington, Charles Russell, and other artists at the birth of Hollywood’s Western film genre. Their depictions of the American West—its landscapes, characters, and mythology—directly shaped the visual language and narrative conventions of early Western films. By placing paintings, sculptures, and illustrations alongside clips from silent Westerns, vintage movie posters, and related ephemera, the exhibition reveals striking parallels between the visual storytelling of these artists and the cinematic techniques employed by early filmmakers.

EXHIBITION ESSAY

A MISDEAL AND THE MOVIES

By Scott Winterrowd

A MISDEAL AND THE MOVIES

By Scott Winterrowd

While numerous books and exhibitions have been dedicated to the influence of Remington, Russell, and other Western artists’ work on the Western film genre in the twentieth century, not much has been said about the influence of their works on early silent films. The discovery of the history of Remington’s painting, A Misdeal and the use of the artist’s work in a group of early silent Westerns became the catalyst for the exhibition, The Cinematic West: The Art That Made The Movies. The following essay details the role of A Misdeal in Hollywood in the twentieth century.

By the time Remington created A Misdeal, he was both writing and illustrating his own stories for periodicals such as Harper’s Weekly in addition to illustrating the works of other writers. The painting was not made as an illustration and is not connected to any narrative text, but the strength of the artist’s visual storytelling would land the picture in the hands and films of moviemakers over the next 60 years and serve as a prototype for countless barroom brawls in Western cinema.

The details of A Misdeal present an open-ended narrative of a card game gone wrong. What exactly has happened is not clear: the room is filled with dissipating gun smoke and wounded cardplayers. One might assume that the central standing figure was cheated and has taken retribution, but he doesn’t appear armed, leaving any clear storyline in question. His gaze draws our attention to the door flooded with daylight and a bystander peering in.

For all that is recorded of the painting’s time in Hollywood, the early provenance of A Misdeal is difficult to trace. As there is no year on the painting, its ascribed date comes from it being reproduced in the first published book of Remington’s art, the 1897 Drawings, published by R. H. Russell. The release of Drawings coincided with a sale of Remington’s art that took place at Hart and Watson’s Gallery in Boston in the fall of 1897, in which A Misdeal appeared. A review of the show published in the Boston Evening Transcript wrote,

“Familiarity with his specialty, and an innate love for the rugged and manly virtues developed by the conditions of existence on the plains, with a keen eye for reality and movement, are the chief merits of Mr. Remington’s art. On the other hand, his indifference to beauty of form, his unfeeling realism, and his poverty of color are formidable handicaps.”

The author went on to write specifically about A Misdeal,

“Nothing that Bret Harte ever wrote about rough camp life in ’49 exceeds in deathly terrors and violence the bar-room shooting scrape depicted under the grimly suggestive title of ‘A Mis-deal.’ This horror reminds one of Colonel Hay’s ‘Mystery of Gilgal,’ wherein it was related how ‘They piled the stiffs outside the door; I reckon there was a cord or more.’” (Boston Evening Transcript, December 8, 1897)

After its sale in 1897, the next time A Misdeal surfaced wasn’t until it made its Hollywood debut in John Ford’s 1918 silent film Hell Bent. In the film’s opening sequence, a writer receives a letter requesting that when writing his next story he should make the hero, “A more ordinary man, as bad as he is good. The public is already tired of such men in novels who embody every virtue. Everyone knows such people do not exist.” The author folds up the letter, rises thoughtfully from his chair, and walks over to a framed image of A Misdeal. As he considers the message, the camera moves in on A Misdeal to frame Remington’s composition more closely. The action comes to life with the next intertitle reading, “What happened?” While characters attend to the central figure standing shot and holding his chest, another intertitle reads, “The Stranger says there was cheating!” Harry Carey’s character, the presumed cheat Cheyenne Harry, then gallops across the dunes in an escape that sets up his storyline as the requested “good-bad” hero.

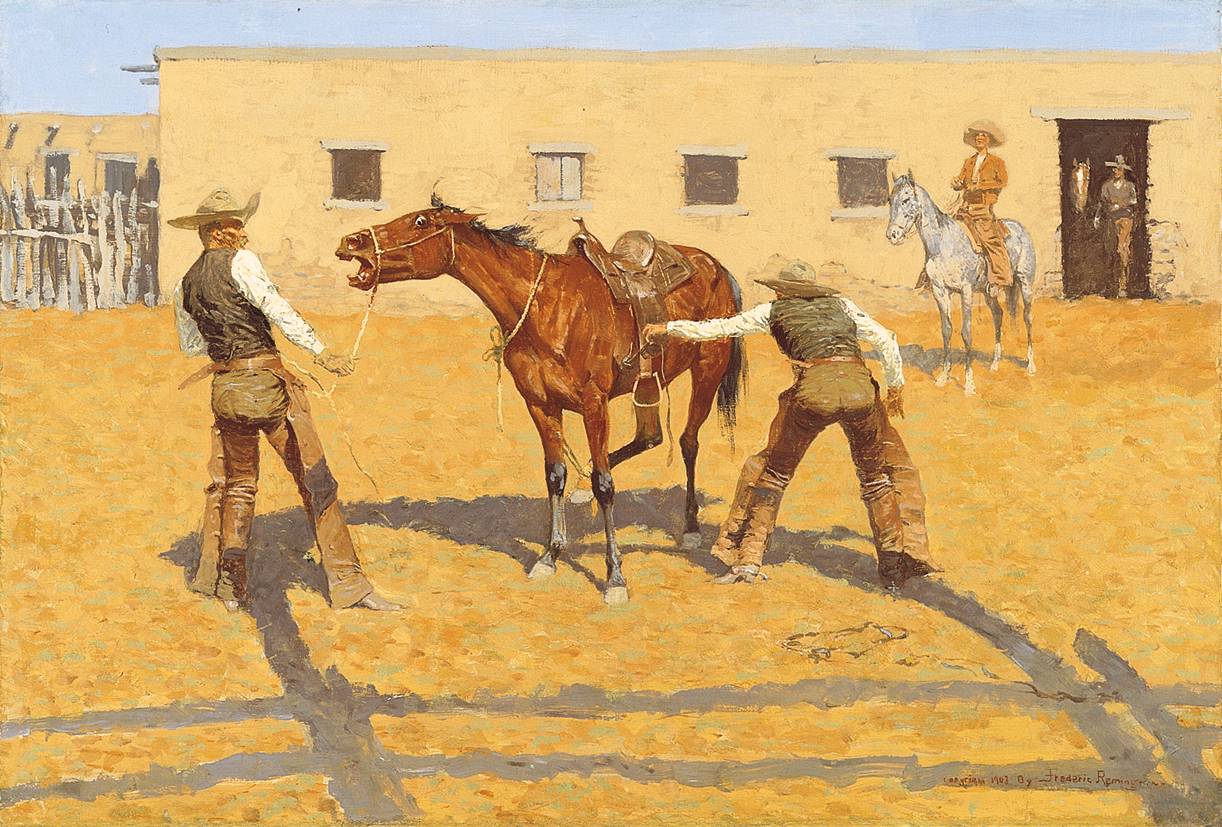

It is unknown how Ford happened to use A Misdeal in Hell Bent. He famously spoke of the influence of Remington and other Western painters when making his classic Westerns from 1939 onward. For this early film the director may have found inspiration in 1917’s Wild and Woolly, starring Douglas Fairbanks and directed by John Emerson. In it, another Remington painting, His First Lesson, 1903, inspires a fantasy sequence where Fairbanks imagines himself in the painting, mounts the central horse, and begins to buck around the corral. Yet another source of filmmaking inspiration may have been Ford’s brother Francis, who introduced him to the movie business. Francis starred in and directed a silent film based on Remington’s only play, John Ermine of Yellowstone, the same year as Wild and Woolly’s debut.

A Misdeal was likely in Hollywood hands by the time Hell Bent was made. One biographer has noted that Douglas Fairbanks began to purchase works by Remington around the time he starred in Wild and Woolly, and records show that he indeed owned A Misdeal at some point. The painting is documented almost a decade later in a photograph with Fairbanks’s wife, actress Mary Pickford, and son Douglas Jr. in their mansion’s basement saloon. A Misdeal would stay with Fairbanks beyond his marriage to Pickford, which ended in 1936, until his untimely death in 1939 at the age of 56. His next wife, Lady Sylvia Ashley, kept the painting until 1953 when she sold it to producer Hal Wallis following her own divorce from actor Clark Gable.

Hal Wallis was a major movie player for over 30 years, producing blockbusters such as The Maltese Falcon (1941), Casablanca (1942), Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957), and True Grit (1969). Beyond his production credits, he was also deeply involved with the film careers of Elvis Presley and the duo Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis. His purchasing of Remington paintings and sculptures took place between 1953 and 1957; unsurprisingly, these years coincide with his work on Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. In a passage in Starmaker: The Autobiography of Hal Wallis, he tells of his relationship with the artist’s work: “I wanted [Gunfight at the O.K. Corral] to have the burned-out, brown look of a Remington painting, and [cameraman Charles] Lang gave it to me. Remington has always been a favorite painter of mine and today several of his finest works hang on the walls of our Palm Springs house.” (Starmaker, page 155)

Beyond A Misdeal, Wallis owned an additional six works by Remington. He would feature much of this collection in the final scenes of the 1961 Dean Martin and Shirley MacLaine film All in a Night’s Work, where A Misdeal hangs prominently in the set. Wallis and his second wife, Martha Hyer, held on to these works by Remington until the early 1980s when A Misdeal and others were sold into private collections.

A Misdeal’s journey—from Remington’s easel to Hollywood’s Golden Age—illustrates the enduring power of Western imagery in shaping cinematic storytelling. Passing through the hands of legendary actors, directors, and producers, the painting not only inspired the look and feel of countless Western films but also became a tangible link between fine art and popular culture. Today, its legacy lives on as a testament to Remington’s influence on the mythology of the American West, both on canvas and on screen.

Still from Hell Bent | John Ford

Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Mary Pickford at Pickfair Costume Party | 1933 | Mary Pickford Private Foundation

Dean Martin and Shirley MacLain admire A Misdeal in All in a Night's Work, 1961

#MuseumFromHome

The Cinematic West: The Art That Made The Movies

Discover how classic Western art helped shape the legends of Hollywood. Take a 360-degree online tour of Sid Richardson Museum’s latest exhibit.