Another Frontier: Frederic Remington’s East

September 14, 2018 – September 8, 2019

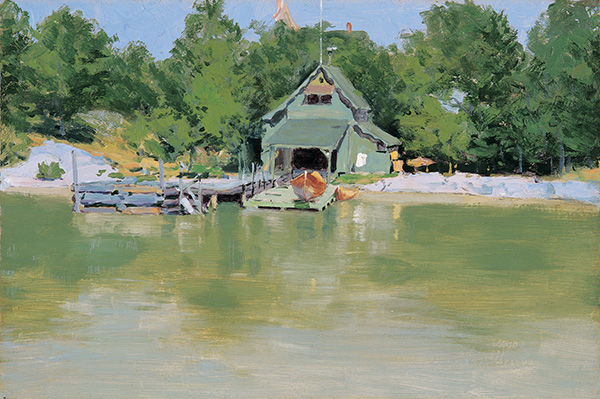

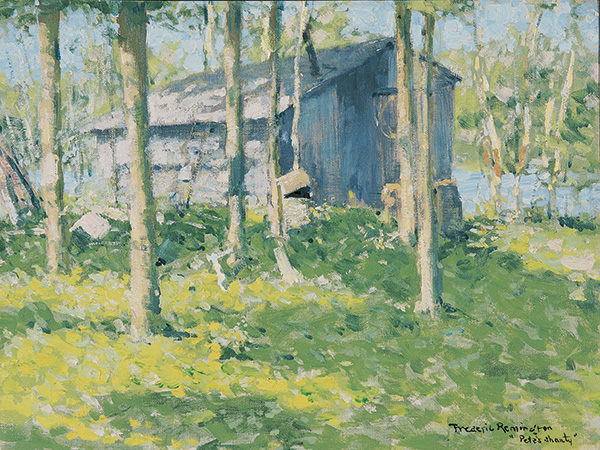

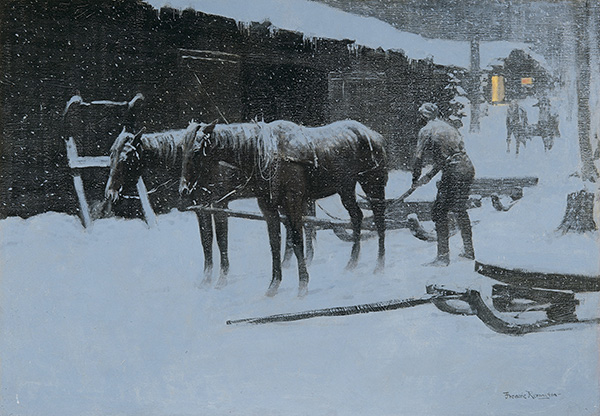

Frederic Remington’s art has so profoundly shaped our perceptions of the Old West that we only vaguely, if at all, recall that he was an Easterner born and bred. He grew up in Canton and Ogdensburg, New York — the North Country, the forested region stretching from the Adirondack Mountains across the St. Lawrence River into Canada. He attended Yale (briefly), settled in the West (also, briefly), and then lived and had studios in New York (Brooklyn, Manhattan, New Rochelle, and Ingleneuk Island) and Ridgefield, Connecticut. He made numerous trips to the West over the years, but composed his multitude of illustrations, paintings, sculptures, and writings in the East. By shifting the focus from his popular Western imagery to his less familiar Eastern subjects, this special exhibition offers visitors the opportunity to expand their knowledge of the context in which Remington worked, while gaining a deeper appreciation of his artistic talent.

The artworks that were on view were on loan from the Frederic Remington Art Museum in Ogdensburg, New York and dated from the first decade of the twentieth century (with one exception). This period in Remington’s life and art was when he yearned to move beyond his popular success as an illustrator to critical fame as a fine artist, when he admitted that “My West passed utterly out of existence so long ago as to make it merely a dream,” and when he became enamored of painting landscapes in a newer style. It was in the East where Remington attempted to resolve his desires, concerns, and interests.

In 1891, the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York City elected Frederic Remington an associate member. However, the Academy never deigned to admit him as a full member, despite support from fellow artists Gilbert Gaul, Childe Hassam, and others. Denying Remington this recognition that he intensely desired undoubtedly centered on the perception that he was more illustrator than artist. This notion gnawed at Remington, and it was only in what, unexpectedly, turned out to be his last years that he received critical recognition as a fine artist. He noted in a late 1909 diary entry the favorable reaction by critics to an exhibition of his works: “They ungrudgingly give me a high place as a ‘mere painter.’ I have been on their trail a long while and they never surrendered while they had a leg to stand on. The ‘illustrator’ phase has become background.”

During this period, Remington continued his prolific production of Western imagery. From 1900 to 1908, he would ship annually several such paintings to Ingleneuk, his island retreat in the St. Lawrence River, and complete them over the summer months. He was also inspired to paint striking North Country compositions, such as The End of the Day and River Drivers in the Spring Break Up. These paintings differed from his Old West scenes by depicting contemporary life. And, although he had rendered landscapes throughout his career, he turned with new vigor to painting the Eastern landscape. One critic wrote approvingly that Remington “has given more study to landscape, and in the northern country, both in winter and summer, has made divers small sketches of uncommon merit.” The artist himself declared in a 1907 interview: “lately some of our American landscape artists—who are the best in the world—have worked their spell over me and to some extent influenced me, in so far as a figure painter can follow in their footsteps.” Being in the East allowed Remington to develop a circle of artist friends and to keep current with art by visiting galleries in New York City.

Among Remington’s many friends, he particularly admired the artworks of Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, John Twachtman, Robert Reid, and J. Alden Weir. Affected by French Impressionism, their art exuded an immediacy and freshness of vision that appealed to Remington: “By gad a fellow has got to trace to keep up now days—the pace is fast. Small canvass [sic] are best—all plein air [outdoor] color and outlines lost—hard outlines are the bane of old painters.” This point of view perhaps explains why he burned “every old canvas” in his house, but saved his landscapes. While Remington thoroughly enjoyed executing quickly-made paintings, he acknowledged a dilemma: “I’d like to paint these things [North Country landscapes and sunsets], but the people won’t stand for it—they want cowboys and Indians . . . .” Remington did include his smaller landscapes in exhibitions of his larger Old West subjects; his fondness for them was evident: “I am going to give the Hepburns [as a thank-you gift] a painting—a small landscape—not the ‘Grand Frontier’ but a small intimate Eastern thing which will sit as a friend at their elbow.”

As hugely important as the West was for Frederic Remington, and he for it, the East was another frontier that nurtured and sustained his art.

Dr. Mark Thistlethwaite, Guest Curator